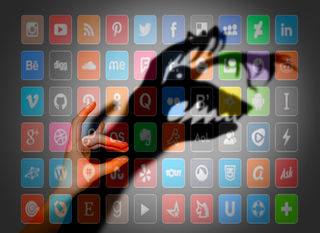

Racially motivated police impropriety is complicated and circumstantial, but ultimately a manifestation of society’s systemic racism. Racial biases permeate our lives via the news and entertainment media – whether it is vilifying Blacks, Latinos, and Gays, or dismissing White America’s issues. These media practices create social disconnect and promote societal dysfunction.

That said consider the police officer’s job. Nobody calls the police to say, “Life is great, stop by and feel the love.” People call the cops to say, “Get over here! Some fool stole everything but my chromosomes.” Imagine the accumulative stress from a job, where you had to wear a gun, and regularly deal with hostility and danger.

Now consider the duress of being Black in America. Stories of police killing Blacks without just cause fill the news; the heartbreak of witnessing the unpunished racist assaults on America's first Biracial President. Imagine knowing that you and your family's skin color are potential death sentences that may be carried out at any given time or place without provocation because some violent racist(s) cannot manage their fear and anger.

Then consider the highly adaptive but predictable and limited brain.

1) The brain consolidates and simplifies, e.g. fight-or-flight is a just a consolidation and simplification of generations of lessons in conflict resolution.[1, 2]

2) When the brain detects a threat, the thinking part of the brain shuts down and the emotional old mammal part of the brain takes over. This section of the brain’s mantra is “bust a move now, think about it later.” Evolution designed the brain this way because when you are in danger, immediate action increases chances of survival, whereas thinking about it decreases those chances. [3]

3) The brain also employs confirmation bias. Meaning, it looks for things to reaffirm its belief-system and ignores information that challenges it. [4-7]These brain proclivities could complicate encounters between Blacks and the police.

For the police, systemic racism consolidates into “Black people are dangerous.”

For Blacks, the collateral damage of systemic racism simplified and combined becomes “The police want to hurt me.”

These beliefs distort perceptions because of confirmation bias. Both people only see and hear that which confirms their beliefs. This scenario may create a downward synergy that could quickly escalate into a horrible outcome, such as the recent events in Louisiana, Minnesota and Dallas, Texas.

Our response to these tragedies is even more disturbing. We single out individuals and events, choose sides, and start tweeting like a flock of parakeets on crystal meth. Once the Twitter lynching and Facebook wars end, we feel like we have had justice, and now we’re ready to have Starbucks. Yet, nothing has changed, except a few more lives have been further decimated. To quote Huey Lewis and the News, “We need a new drug.”

New drug or new bug?

“Most people would agree that negative emotions such as fear and anger are at the basis of racism. Many factors contribute to these deep-rooted emotional traits and the underlying alterations in the brain’s ability to control them. We are now beginning to identify the important role of gut microbes in the early development of these brain systems that play a role in emotion regulation and stress responsiveness. Even in adults – animals and humans, changes in the gut microbiome produced by the regular intake of a probiotic can dampen the brain's responsiveness to negative emotional stimuli,“ says Emeran Mayer, MD, Ph.D., director of UCLA’s Center for the Neurobiology of Stress.

In his latest book, The Mind-Gut Connection, Dr. Mayer discusses how the brain and gut interaction influences stress regulation and emotional management.

“I wrote this book because of the lack of concrete information regarding how the gut microbiome affects our mental states. People have written some very speculative and provocative review articles about how microbes might regulate human emotions. What I have tried to do is be critical and extract what we know so far and speculate about what this could imply,” Mayer added.

Our gut produces considerably more serotonin than the brain.[8-10] Serotonin is necessary for the more developed thinking part of the brain to intervene on the purely emotional old mammal part of the brain.[11-14] So, when we look at incidents, like those recently in the news and ask ourselves, “what were they thinking,” – the answer is they weren’t. The old mammal brain was in control, and it does not think.

So maybe we should become more of a probiotic nation, than a Prozac nation. Directing our energy towards better understanding the nexus of humans, microbes, the brain, and emotions would serve us better than memes and tweets that demonize people who conceivably did what we all might have done if we were in the same situation with the same variables. The human brain is highly adaptive but equally vulnerable to context and circumstance – that's what makes humans human. So, when a travesty occurs, consider compassion and moving towards higher ground rather than lower.

"I do not believe there is a way in which this deeply entrenched evil (American racism against Blacks) can be quickly healed. But until this goal is reached there is no greater satisfaction for a just and well-meaning person than the knowledge that he has devoted his best energies to the service of the good cause." -Albert Einstein (1946) As always, remain fabulous and phenomenal!

Join my email list to receive notifications of new posts

UCLA Center for the Neurobiology of Stress

References

1. McEwen, B.S., Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev, 2007. 87(3): p. 873-904.

2. Ranabir, S. and K. Reetu, Stress and hormones. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2011. 15(1): p. 18-22.

3. McEwen, B., Lasley, E, End of Stress as we know it. 2002, Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press.

4. Downar, J., M. Bhatt, and P.R. Montague, Neural correlates of effective learning in experienced medical decision-makers. PLoS One, 2011. 6(11): p. e27768.

5. Todd, J., A. Provost, and G. Cooper, Lasting first impressions: a conservative bias in automatic filters of the acoustic environment. Neuropsychologia, 2011. 49(12): p. 3399-405.

6. Doll, B.B., K.E. Hutchison, and M.J. Frank, Dopaminergic genes predict individual differences in susceptibility to confirmation bias. J Neurosci, 2011. 31(16): p. 6188-98.

7. Bronfman, Z.Z., et al., Decisions reduce sensitivity to subsequent information. Proc Biol Sci, 2015. 282(1810).

8. Tillisch, K., et al., Studying the brain-gut axis with pharmacological imaging. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2008. 1144: p. 256-64.

9. Lesch, K.P. and L. Gutknecht, Pharmacogenetics of the serotonin transporter. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2005. 29(6): p. 1062-73.

10. Bercik, P., et al., The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology, 2011. 141(2): p. 599-609, 609 e1-3.

11. Petty, F., et al., Serotonin dysfunction disorders: a behavioral neurochemistry perspective. J Clin Psychiatry, 1996. 57 Suppl 8: p. 11-6.

12. Sodhi, M.S. and E. Sanders-Bush, Serotonin and brain development. Int Rev Neurobiol, 2004. 59: p. 111-74.

13. Schaefer, A., et al., Serotonergic modulation of intrinsic functional connectivity. Curr Biol, 2014. 24(19): p. 2314-8.

14. Bearer, E.L., et al., Reward circuitry is perturbed in the absence of the serotonin transporter. Neuroimage, 2009. 46(4): p. 1091-104.