Attention

How Well Do You Know the World You Live In?

Our mental health may depend on deepening our sense of place.

Posted January 4, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

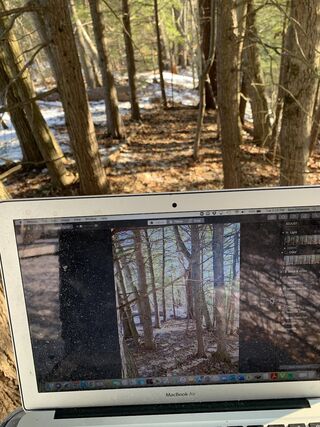

Since I live rather rurally, I take long walks most every day, meandering along the dirt roads that pass by and through old growth forests near my house. The part of NH where I live is pretty hilly, so I even have my “aerobic walk” to replace the gym I don’t visit these pandemic days. Recently, I interrupted a day busy with Zoom meetings and work at my computer with one of my favorite walks. I was gone an hour, on a glorious snowy day, the woods draped in white, the air crisp with the feel and scent of winter.

At least I think that’s what I encountered. I can’t be sure because when I walked back into my house I realized that I had been so deep in thought that I hadn’t looked at the scenery or felt what was around me at all. I was busy thinking about the last meeting I’d come out of, the next one coming, an article I am working on, and would I get to see my granddaughter over Christmas?

My attention was so focused on my thoughts that I’d paid hardly any attention to the vibrant world around me.

It was ironic, and fortunate, that Mitch Thomashow’s new book recently landed on my desk. The title is To Know the World and Thomashow, an environmental educator, bills it as a “new vision for environmental learning.” Environmental studies is a big deal in education these days, and hopefully, it’ll get bigger, but what really interests me about Thomashow’s writing is the way in which he works to get us all to think about how well we know—that is, deeply experience—the world around us.

Thomashow is concerned with the increasing amount of time that people are spending on screens and the two-dimensional pixel world, the amount of working indoors, and the way that our direct experience of the natural world is impoverished by the loss of the “sensory and sensual awareness of the biosphere.”

This is territory that has been explored also in Richard Louv’s work on “nature-deficit disorder” and Sherry Turkle’s research on the way that technology serves to isolate us, leaving us “alone together.”

Thomashow’s contribution is to put our increasing distance from the natural world in the context of the ongoing climate crisis and to show how we can lose the essence of what it means to be human if we get too cut off from the “visceral experience of natural systems.” He argues, “You can’t understand the meaning of humanity if humans are the only species you care to interact with. Whether it’s the menagerie of microbes that live in your body, the trees in your local park, the birds that arrive at your feeder, or the river that flows through the heart of your city, observing the natural world is the last chance you have to understand what it means to be human on a planet with approximately 8.7 million species.”

What to do then, exactly? While Thomashow can—and does—explore the importance of systems-based thinking, he also can be quite pragmatic and personal in his recommendations for ways to counter the “collective spell” of screens in a consumer-driven economy that threatens to separate us from the natural world. He wants us to reclaim our attention from the ubiquitous temptation of cell phones, iPads, laptops, television, and other aspects of “consumer capitalism, social media, and internet connectivity.”

This is not an easy task, given the addictive quality of screens in our lives. (“Oh, I’ll just take a moment to check my email,” “Excuse me, I just got a text, be right back.”) Thomashow proposes focusing our attention on our “ecological place” to reclaim our capacity to think and feel in a more deeply human way. He wants us to “read the day,” and juxtaposes two different ways of getting up in the morning: “You can step outdoors wherever you may be in order to feel the temperature, wind conditions, light, sounds, and smells… Or you can immediately glance at your phone to check your messages, email, or whatever virtual information that gets you oriented.” No matter how you greet the day, he suggests adding the intention to notice these details of place to your routine. He suggests deliberate pauses in what you are doing to become attentive to the visceral details of the here and now around you

In the course of the book, Thomashow offers several fine-grained suggestions for how to pay attention to the ecological place around you:

“Notice the interface between indoors and outdoors when you leave a building or step out of a vehicle.

“Look away from your screen and refocus your gaze on the biggest perceptual field you can find.

“During a commercial or break when you are being entertained, mute the sound, close your eyes, and focus on the acoustics of the room you’re in.

“As you walk from one place to another, leave your planning behind, and pay attention to every nonhuman living thing.”

Does this seem like good meditation practice? It does to me; the sort of “good noticing” that meditation teachers advocate as part of mindfulness training.

What Thomashow adds to this is an awareness of the ecological intertwining of humans with the planet. We know that the trees, plants, fungi, and microbes in a forest are all interconnected through a threadlike mycorrhizal network. Anyone who has felt the effects of a “forest bath” may understand the way in which being human means being part of this interconnected relationship of species.

Does being human—our mental, physical, and spiritual health—mean becoming more viscerally aware of this world? To care for it, and to recognize our embeddedness in it? These are the questions Thomashow raises, and he provides some new directions for people who want to explore them.

I vowed to be more intentional about knowing my “ecological place” as I threw on my coat for a walk on a recent cold winter’s day. Inside the house, my head was filled with concepts and ideas as I bundled up. When I stepped outside, I made sure to notice the cold air—its bracing impact on my skin, the snowy smell, the pristine clarity of sight such weather provides. The familiar road under my feet crunched unexpectedly, the sound of pebbles, snow, minute pieces of ice. The tree branches were heavy with snow, each trunk with its own splash of whiteness against its arrangement of lichen, white dancing with varieties of green, each with its own texture. I passed a familiar brook, and this time I really heard the sound of its rushing water, curling through patches of ice forming along the banks.

Midway down the empty road, I stopped at a bank of deciduous ferns that I watch every summer grow atop a great rock, like a miniature metropolis balanced on an asteroid. They were buried in the snow, leaves gone, bundled up for the winter. And connected with each other through their mycorrhizal network, waiting for the warmth of spring.

I took in the deep silence of a snowy day in the woods.

I felt the emptiness of the world, indifferent to human intention and desire.

I felt the connectedness of all things in this world, the unseen bonds that unite it all.

I felt grateful to be alive.