Environment

Waking Up In Ecuador: In Evolution's Workshop

Where humanity discovered how nature works, and our place in it. Part II.

Posted June 10, 2019

Am I a climate denier in my inattention to the natural world around me? Do I need to learn to really look and see the beauty and richness of what is imperiled as I rush through my busy, everyday life, insulated from nature?

Such were the thoughts on my crowded mind as we returned to Quito from the Andes for our flight to Baltra airport in the Galapagos Islands, the land of flightless cormorants, blue-footed boobies, and otherworldly lava- strewn beaches.

First, a note about why the Galapagos are occupy such a revered place in human history.

The Galapagos Islands are a chain of nineteen islands—only four inhabited—rising out of the Pacific six hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador, spanning the Equator. The Galapagos National Park and surrounding marine reserve (second largest in the world) cover over 51,000 square miles and comprise a UNESCO World Heritage site. The continuing volcanic activity that formed the islands and their predecessors (there are a number of undersea islands that have eroded as they’ve moved toward the coast of Ecuador) creates a sort of conveyor belt of islands that moves toward the mainland at the rate a human fingernail grows per year, calved by the movement of tectonic plates.

The abundance of land and sea life is astounding. Finches, giant tortoises, land iquanas, red and blue footed boobies, mocking birds, penguins, pelicans, herons, magnificent fork-tailed frigate birds, flightless cormorants, unique flora such as giant daisy trees (Scaleia) and the Galapagos Fern tree, varieties of sharks, whale sharks, rays, pilot whales, sea horses, marine iguanas, and sea turtles. And of course sea lions-- many of them

The Islands are carefully regulated. There are a total of 85 boats licensed to take tourists on navigations, with licenses strictly regulated. There are no Air BnBs allowed on the Islands and there is a current cap on hotel space with no further construction currently planned. Still, there are a total of 240,000 visitors per year.

The Galapagos are the place where the human species’ hubris and ignorance (at least the Western European, Judeo-Christian variety) finally crashed into reality. Prior to the discovery of the Americas, the unquestioned belief was that the earth was created to serve humankind’s delight and edification–the thinking went: it had been created at one time and stayed unchanging since, perfect as is God’s work. The aim of natural science was to figure out the best uses for the animals and plants that were “God’s bounty” given to the devout. Humans, created in the image of God, had dominion over the earth and the European explorers of the sixteenth and seventeenth century (mainly Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, British, and French) proceeded apace to plunder the Americas.

Except for the Galapagos Islands. These islands presented a problem in their seemingly desolate, unoccupied, often lava- ridden geology and in the odd, never-seen-before nature of the wildlife and flora found there. Who could have created such beasts and to what end? Why were they only found on the Galapagos and nowhere else? Herman Melville, who visited the Galapagos while working on a whaling ship (experiences that became the basis for “Moby Dick”), pronounced the Islands “evil” and “enchanted” (in a bad way). Europeans generally avoided them.

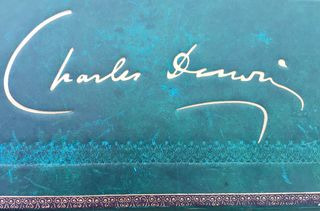

Until Charles Darwin arrived. In what can be seen as the most revolutionary act of human thinking, Darwin came to understand–after long and tormented study—that the central dynamic in all of nature, including human beings, was evolution and the natural selection of species. The place of God in all this—and more importantly, the role of man on this earth–suddenly became very precarious indeed. No wonder Edward Larson titled his eminently readable history of the Galapagos, “Evolution’s Workshop.”

*

The storied place of the Galapagos in our dawning awareness of how nature really works was palpable the moment our airplane landed at Baltra island airport. Among the first species we were treated to were two leashed dogs sniffing all our luggage at the baggage carousel while officers asked passengers to wait behind a yellow line several feet away.

The dogs were not looking for drugs. They were part of the “Canine Sniffer unit,” tasked with detecting contraband substances that have the potential to introduce new invasive species into the archipelago (such as oranges, mangos, cheese, sheep’s wool and other organic items that carry potentially disruptive seeds, fungi and bacteria).

Here was the first reminder that the evolutionary prize goes to the species most adept at adapting to its environment (invasive species generally have no natural predators.) To really protect an ecosystem you have to check your species privilege at the airport and think differently. Gee, what’s wrong with a lousy orange?

Awareness is emphasized, as if the islanders understand their role as shepherds of a deeper truth about being human. As in Aldous Huxley’s Island, signs proliferate urging attention to the here and now: “Silence is your greatest ally in enjoying nature”, “You are in one of the most natural paradises on earth. Please don’t litter.” We need to be reminded to really look and to see. And to not despoil the treasures around us with candy wrappers and plastic straws. We bring our habits—and our entitlement-- with us. Being in the Galapagos was like a long, long meditation session: bring your awareness back, over and over again. You do not own this marvelous world. You are simply a part of it.

Awareness is one thing, felt experience another. What happened next, after we boarded the Beagle and headed into the Galapagos archipelago, was a lesson in felt kinship with the animal life around me.

Next: In The Galapagos With Darwin and Diego