Psychoanalysis

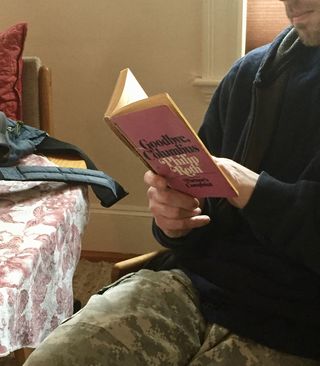

Thank You, Philip Roth

What one book helped propel you into adulthood?

Posted November 28, 2018

It really wasn’t about the sex, though that was funny. No, what most blew my mind reading Portnoy’s Complaint—scrunched in the back seat of a VW bug, yelling at my friends, "You’ve got to read this!”—when it first appeared back in 1969, was the irreverence.

Sure, Nathan Portnoy was doing unspeakable things to the family dinner, and engaging in all sorts of sexual gymnastics in the most forbidden of public spaces—but in writing about it with the verbal pyrotechnics that only he seemed capable of (what has come to be fondly known as, “the Rothian rant”), Philip Roth was also wagging his…finger at the stodgy sensibility that dominated American Jewry after the Second World War.

[Full disclosure: I never met Roth, yet his death on May 22 this year felt like a death in the family. Judging from the outpouring of writing about him, I was not alone.]

For a twenty-something Jewish man coming of age in the sixties, Portnoy’s Complaint was an invitation to a more authentic sense of self as an American and a Jew.

In our age of Jon Stewart, Sasha Baron Cohen, Amy Schumer, and Marc Maron, it may be hard to remember the fog of anxiety that surrounded being Jewish after the Second World War right into the 1960s.

The Holocaust was a trauma that had barely come to consciousness—it wasn’t until the late 1950’s that the NY Times headlined, “Six Million Jews Said To Have Died in Concentration Camps“—Israel was not at all a sure thing, and the virulent anti-Semitism in this country lurked just beneath the pleasant platitudes of the 1950s. (The fate of the Rosenbergs and the humiliating of Robert Oppenheimer, part of “the Red Scare”—or Jew Scare—were evidence of that.)

Redlining of Jews (and blacks) was an ongoing thing—in the 1950s, when I was 7 years old, my parents were sold a house in the “Jewish” section of our leafy suburb of New York City after being told that the fancier center was not for them: "You wouldn’t like it there.”

Jews were timid, with reason. We were afraid. We wanted to be nice, to fit in, and not anger “the Gentiles.” Hence the virulent reaction to Portnoy’s Complaint from the Jewish establishment. Roth was pilloried for “giving the goyim exactly what they want.”

Well, Roth gave this Jew exactly what he needed. In the author who created Alex Portnoy, I saw a smart, verbal, wise-cracking Jew who was not afraid to put contradictory and anguished feelings into words—irreverent, comic words, to boot.

In writing Portnoy’s Complaint, Roth said to me: You can be a Jew in this country and you don’t have to hide it. You can be cocky, you can be brazen, you can say what needs to be said.

And: You don’t have to bow down and be reverent in the face of authority, Jewish or otherwise. To a young Jewish graduate student in psychology, this was catnip.

The book said to me: Don’t be so afraid! Crack a joke, it may open up the truth for you. You want to be an academic, you want to make a career? OK, don’t just accept authority, transform it. You want to be an American? OK, don’t just accept the established version, transform it.

This is the challenge facing immigrant families: How can the children remember where they came from without being dominated and suffocated by it?

In that sense, Roth fits into the grand Jewish comedic tradition of portraying the most serious of questions in a way that makes you laugh…when you’re not weeping. Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, Sarah Silverman, and Lewis Black owe a lot to the door that Roth opened.

Portnoy’s Complaint is structured as one long screed within a single session of psychoanalysis. The last sentence of the book is the first time the psychoanalyst (clearly an immigrant himself, of European extraction) speaks: “So. Now vee may perhaps to begin.”

And that’s what Roth did in the amazing set of novels that followed Portnoy. In an interview with Terry Gross on NPR, Roth revealed that the years 1962-1967 were a period where he was still trying to find his voice and where he started and abandoned several novels. While Roth has expressed regret at writing Portnoy, given the harassment and misreadings that followed, it’s hard to imagine that the marvelous string of succeeding novels could have happened without Portnoy. The book reads like a personal liberation as well.

In the novels that followed, Roth explored how to be an American who remembers that he is Jewish. Not a Jewish-American or an American Jew, phrases he objected to, but rather an American who remembers where he came from. The Counterlife, Operation Shylock, The Plot Against America, and many others, were in part an exploration of how to be profoundly aware of your Jewishness without being squashed by false gods. His rants on “rock worship” at the Western wall in Jerusalem in Operation Shylock are pure gold, as are his alternately funny and painful portrayals of trying to be an American (Jew) in Israel, and—in The Counterlife, in England.

No wonder Roth spoke in 2002 in transformative ways about what it means to be an American:

“I have never conceived of myself for the length of a single sentence as an American Jewish or Jewish American writer, any more than I imagine Dreiser and Hemingway and Cheever thought of themselves while at work as American Christian or Christian American or just plain Christian writers. As a novelist, I think of myself, and have from the beginning, as a free American and—though I am hardly unaware of the general prejudice that persisted here against my kind till not that long ago—as irrefutably American, fastened throughout my life to the American moment, under the spell of the country’s past, partaking of its drama and destiny, and writing in the rich native tongue by which I am possessed.”

Roth was presenting to us an image of a “free American” who can use language to give voice to his particular vision of what it means to be an American. Roth’s belief that our country’s “moment” lies in its transformative ability to integrate diversity, rather than any single Christian or white vision of America is a profound reminder of what this country can be. Though he might not love the word “diversity,” he clearly believed in the power of words to set “to set loose (in readers) the consciousness that’s otherwise conditioned and hemmed in,” as he said in a Paris Review interview.

That’s what great books do for us: They set loose a consciousness of who we are and what words can do, whether it is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah or Jumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake or Julie Alvarez’s How The Garcia Girls Lost Their Accent or Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You or Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West.

These works root us in the wobble, the despair, and the hope, the sometimes comic, often tragic, ways that people struggle across generations and time for a sense of identity in a new place. Great novels transform the American immigrant imagination.

In Roth’s hopeful view, the power of America is to transform identity into something more than just “me” versus “them.”

He offered us a vision of an America that we sorely need in these difficult times.