Environment

Making Your Mind Up

It might be easier than you think.

Posted March 7, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- When we are indecisive, we want two different things simultaneously.

- Any goal we pursue has a more highly valued goal in the background.

- Reflecting on why we want what we want may reveal a more important goal that will provide clarity and assuredness.

Have you ever told anyone else to make their mind up? Has anyone ever told you to do that? Perhaps you’re holding up the meal order because you can’t decide between the eggs Benedict or the chef’s special omelet. Maybe you’re at the front of the queue and can’t decide which new release blockbuster to buy a ticket for. Or are you at the market taking up the vendor’s time choosing the best three mangoes to buy while other customers gather?

A mind that is not made up is messy and indecisive. To someone on the outside, it can appear chaotic and irrational. As someone in the company of this mind, perhaps you hear it say one thing and then the opposite. Does the mind want to stick to its studies to get better qualified but also want to quit and look for another job?

You might notice that when you can’t make up your mind, you feel stuck or pulled between different alternatives. Do you want to stay and put up with the abuse or leave and face uncertainty?

A made-up mind is clear and decisive. It is reconciled. It is content. Resolute. Tranquil. Made-up minds are in harmony with themselves. They are an internal collaboration surging in the same direction, achieving the things they desire. A mind at one with itself usually doesn't even stop to notice that that's what it is or that it is working in sync with itself. It just gets on doing and being.

It seems to be in our nature to move between states of clarity and periods of indecision. Life can go along swimmingly until an unexpected turn of events throws you a curve ball. You might have a job you enjoy in which you feel settled and confident until a new person commences who is condescending and critical. Suddenly, the environment in which you felt secure has become hostile. What do you do?

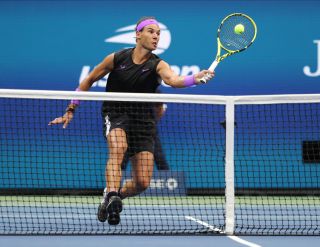

Indecision can last a millisecond, but still dump a deluge on you. The sporting arena has an endless stream of examples of people who hesitated only ever so briefly but enough to change the result. A tennis player who plans for a passing shot but then thinks about a lob will probably end up handing their opponent an easy put-away volley. The phenomenon of “choking” is likely to have indecision at its foundation. The mind of a champion is uncluttered, clear, and focused.

We might not be able to prevent times of uncertainty and doubt, but there is a way we can speed up how swiftly we move through them.

Ironically, the clue to making your mind up is contained in the phrase itself. The key word is “up.” The way to make your mind up is to go up. I don’t mean you should find an elevator or buy a plane ticket. I’m talking about "up" in your mind. For every goal we concoct, there is a goal above it that it serves. That’s no more mysterious than thinking about why you do things. Why are you considering the eggs Benedict? Why are you drawn to the chef’s special omelet?

The “up” is important because that’s where you’ll find sparkling clarity. Somewhere in the up place–you might have to make more than one stop–you’ll find the goal that both current squabbling goals are trying to appease. The up goal just wants what it wants. It’s not so bothered about how it gets it.

So, once you get an inkling of the upper want, the way there will be a breeze. You might even find yourself wondering what all the fuss was about.

The making of your mind is all about the “up.” The more time you can spend in those up places, the more mind-making will occur and the clearer your life will seem. Lots of fun is to be had down in the trenches, too, but for sureness and focus spend some time in the up.