We shouldn’t try to get rid of anger, which seems to be the mistaken goal of some new age-y groups and some Buddhist-influenced practitioners. Anger is not always destructive; it wouldn’t have been preserved over the course of the evolution of our species if it was inherently harmful to us. Those who argue that anger may have once been useful but in our contemporary circumstances no longer is, I think are wrong. Let me explain why.

Even in the most civilized settings we can’t completely avoid encountering a circumstance in which we are threatened with physical assault. Anger then provides the force needed to defend ourselves. But it is not only in such dire circumstances that anger can be beneficial. Anger can motivate actions undertaken to correct social injustices. Anger can motivate actions to diminish or, if we are lucky, turn back climate change. Even in personal relations, with our family members or intimate partners, anger can be useful. Is that surprising?

Anger tells us we have a problem that ideally we should deal with when we are no longer angry. Sometimes we can’t postpone; we must deal with a provocation or interference without postponing pursuit of our goal. What then? It requires skill to focus our anger on the actions — not the actor — that are either causing (or threatening) harm or blocking our path.

I believe that harming the person interfering with us is so often a goal when we are angry that it may well be built into the very nature of anger. But it can be redirected to stop the actions of the interfering person instead of attempting to harm the actor. Often those who act angrily regret later what they said or did. It is not uncommon for a person to explain the actions which they later consider regrettable with a remark such as ‘I lost my head’. You can give it back to them!

One way to do that is by helping the angry person calm down. If the angry person doesn’t ask for a ‘time-out’, you need to. The time-out works best if you have had a prior discussion of its benefits when matters may be getting too hot. Anyone should have the right to call a time-out, and by prior agreement it must be granted. It takes presence of mind to ask for a time-out rather than reciprocate anger directed at you.

Think for a moment about the phrase: presence of mind. It means you must be consciously aware of what you are thinking and considering doing. Your response to someone’s anger directed at you must resist the impulse to reciprocate anger. It is especially hard to do when you think their anger is totally unjustified. It is hard not to reciprocate anger, for I believe that anger inherently tempts its target to join in the battle. Don’t do it. Taking a time-out will help you resist the urge to hit back, figuratively or physically. The initial angry person who set it off will thank you for stopping his or her outburst even if that person isn’t able to say so.

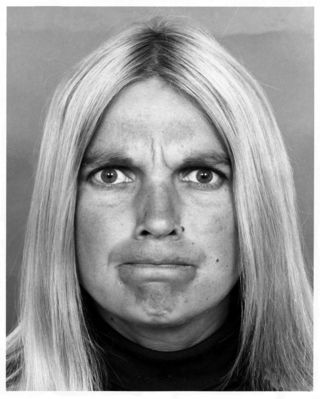

When we get angry or someone gets angry at us, it shouldn’t be ignored. Anger can be communicated not just by words, but also by facial expressions. This emotion is an important sign that there is a problem or a misperception that needs to be addressed. Just don’t try to do it in the heat of anger. We need to find out what provoked the anger and see if we can correct it. The most common trigger for anger is frustration, felt typically when our pursuit of something that matters to us is blocked. Anger is rarely useful in removing a block, but it does tell us that there is a block that needs to be identified, examined, and hopefully diminished or eliminated. That rarely can be accomplished when we are still angry.

We need to take our time. Calm down. Think it over. Discuss it and then jointly remove the block, or if it can’t be removed, arrive at a way to live with it. It is almost always possible, just not necessarily easily or quickly, but in the long run it is what will sustain collaboration with others. Collaborating with others is a necessary condition of the life of all social animals. We can’t make it alone; and, it is more enjoyable when we accomplish a goal together.

Dr. Paul Ekman is a well-known psychologist and co-discoverer of micro expressions. He was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by TIME magazine in 2009. He has worked with many government agencies, domestic and abroad. Dr. Ekman has compiled over 40 years of his research to create comprehensive training tools to read the hidden emotions of those around you. To learn more, please visit: www.paulekman.com.