Eating Disorders

Body Image in Eating Disorders

The central role of the overvaluation of shape and weight.

Posted August 2, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- The overvaluation of shape and weight is central in the maintenance of body image disturbance in people with eating disorders.

- It is addressed indirectly, enhancing the importance of other self-evaluation domains, and directly addressing its main expressions.

- The main expression of the overvaluation of shape and weight to address are body checking, body avoidance, and feeling fat.

Body image disturbance is one of the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, but not for binge-eating disorder. It is associated with greater severity of eating-related psychopathology and psychological distress and is also a predictor of adolescent eating disturbance. Body image disturbance is also one of the most important prognostic factors in treating bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder.

Body image is a multidimensional construct that includes cognitive, behavioral, affective, and perceptual components. However, interest in the perceptual component, measured with body size estimation techniques, has gradually diminished due to uncertainty over its specificity and the unresolved methodological and theoretical confusion over its measurement. Instead, the cognitive behavioral theory of eating disorders places more emphasis on a specific cognitive component of body image disturbance, the overvaluation of shape and weight, as their distinctive “core psychopathology."

The Overvaluation of Shape and Weight

People with eating disorders tend to judge their self-worth predominantly or even exclusively in terms of shape, weight, and their control. This psychological feature is common to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and occurs in more than 50% of patients with binge-eating disorder, as well as a large subgroup of other specified eating disorders.

The overvaluation of shape and weight is unique to the eating disorders both in females and males and is rarely seen in the general population. Indeed, people without eating disorders generally evaluate themselves on the basis of their perceived performance in a variety of other life domains, e.g., relationships, work, sport, and parenting.

Overvaluation of shape and weight should be differentiated from body dissatisfaction, as the latter is common in people without eating disorders and is less closely associated with self-esteem than the former.

Overvaluation of Shape and Weight as a Central Eating Disorder Maintenance Mechanism

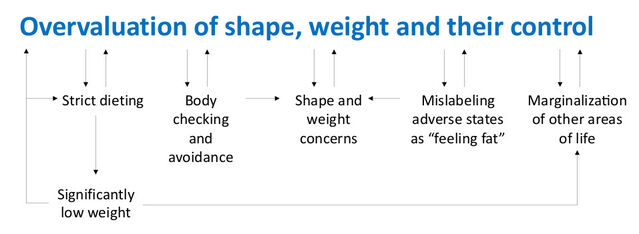

Most clinical features of eating disorders stem directly or indirectly from the overvaluation of shape and weight, and this core feature is of primary importance in maintaining eating disorder psychopathology (Figure 1).

The central role of the overvaluation of shape and weight in the maintenance of eating disorder psychopathology is supported by the following evidence:

- Among patients with bulimia nervosa who showed a full response to treatment, those with the highest residual level of overvaluation of shape and weight were most prone to relapse.

- Trials of two psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa have shown that behavioral approaches that did not address the overvaluation of shape and weight were associated with a greater risk of relapse than those that did.

Addressing the overvaluation of shape and weight

Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) places great emphasis on addressing the overvaluation of shape and weight and its expressions through a specific “Body Image Module” featuring specific integrated multimodal strategies and procedures (Table 1).

Table 1. Main strategies and procedures of the CBT-E Body Image Module

1. Identifying overvaluation and its consequences

2. Enhancing the importance of other self-evaluation domains

3. Reducing the importance of shape and weight

• Addressing body checking

• Addressing body avoidance

• Addressing feeling fat

4. Exploring the origins of overvaluation of shape and weight

1. Identifying Overvaluation and Its Consequences

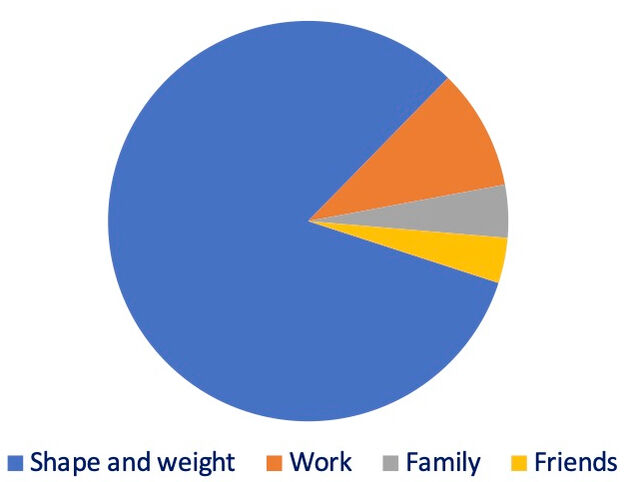

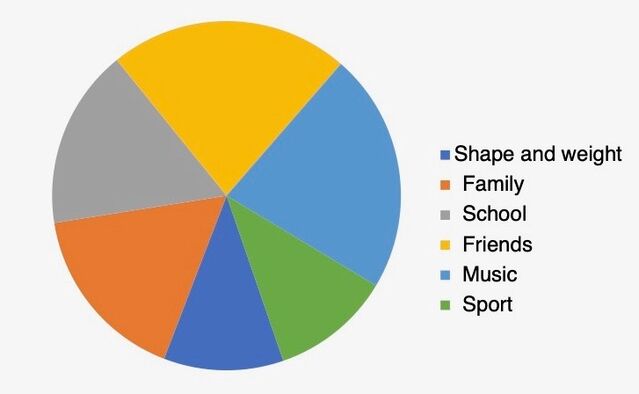

Patients first need to be educated on the concept of self-evaluation. To draw up their personal self-evaluation schema, the therapist helps the patient generate a list of life areas that are important to their self-worth. Then it is collaboratively drawn a pie chart in which each slice is used to represent the relative importance that the patient attaches to that area of life in their self-evaluation schema (Figure 2), which can be discerned from the intensity and duration of the patients’ response to things going badly in each area.

The pie chart provides the patient with a visual representation of the excessive importance they give to shape, weight and their control and can be used by the therapist to elicit the advantages and disadvantages of using a system of self-evaluation based predominantly on that domain. Through this type of analysis, the patient is led to the conclusion that, although having one predominant self-evaluation domain may have short-term advantages—it is simpler to gauge self-worth via a single, controllable, and measurable domain—it is in fact a dysfunctional form of self-evaluation in the long term. Indeed, it severely marginalizes other important aspects of life (e.g., relationships, school, work, hobbies). It can also be linked directly or indirectly to behaviors that characterize and maintain eating problems (e.g., strict dieting, binge-eating episodes), and produces severe physical and psychosocial complications. Furthermore, although a single criterion may improve mood when things are going well, if something goes wrong (e.g., weight gain or a binge-eating episode), it inevitably leads to a collapse of self-worth.

2. Enhancing the Importance of Other Self-Evaluation Domains

This strategy involves helping patients identify any activities or areas of life they would like to work on and assist them in doing so. The aim is for patients to increase the number and significance of other self-evaluation domains, particularly in the interpersonal sphere, and indirectly reduce their overvaluation of shape and weight.

3. Reducing the Importance of Shape and Weight

A second direct strategy is to target the behavioral expressions of the patient’s overvaluation of shape and weight. This strategy is applied simultaneously as enhancing the importance of other self-evaluation domains and involves tackling behaviors linked to body checking, body avoidance, and feeling fat.

Addressing Body Checking

Body checking is common among healthy individuals, but in those who tend to overvalue shape and weight, it manifests far more frequently and in very unusual ways; for example, standing naked in front of the mirror for long periods and looking at the body from different angles.

Body checking maintains overvaluation of shape and weight through several mechanisms:

- Repeated scrutiny of “unsatisfactory” parts of the body tends to magnify apparent defects.

- Focusing on specific parts of the body in isolation rather than the body as a whole increases body dissatisfaction because it maintains the “problem” continually under the eyes.

- Paying superficial attention to the body parts of atypical persons (e.g., models or actresses), thin people, or those with idealized features (e.g., a flat stomach) confirms the patients’ belief that their body is the wrong size and shape.

- Frequently checking body weight may lead to erroneous interpretation of minimal changes (generally due to hydration status) as a sign of “getting fat” thereby promoting an increase in dietary restraint.

Patients need to be educated about the adverse effects of abnormal body checking and monitor for any episodes occurring over two days to assess their frequency and implications.

Typical body checking behaviors to address are dysfunctional mirror use focusing on specific body parts (which magnify apparent defects) and comparison with thin, attractive people (a behavior that can only lead to the conclusion that one is fat and unattractive). In cases where this type of unhealthy comparison is focused on celebrities shown in magazines, one helpful strategy may be to point out to patients that such images are not representative of realistic body models (there are numerous examples of “The Photoshop Effect” on the internet which may be helpful in this regard).

Addressing Body Avoidance

Body avoidance acts to maintain body dissatisfaction and, therefore the overvaluation of shape and weight itself. This happens because not having a clear idea of one’s appearance tends to foster concerns and fears about shape and weight. Body avoidance is also a huge obstacle to healthy socialization, intimacy with a partner, and everyday activities such as clothes shopping or swimming.

Typical body avoidance behaviors include avoiding: (1) checking body weight, (2) looking at one’s own body, (3) touching one’s own body, and (4) exposing one’s body to others.

Body avoidance is addressed via a “gradual exposure” strategy, in which the therapist helps patients identify their main manifestations of body avoidance. Thus enlightened, they can be assisted to plan and progressively enact exposure of specific body parts, beginning with those that cause less discomfort. In this way, patients gradually become accustomed to the sight and feel of their own body and ultimately feel comfortable exposing it in the presence of others.

Addressing Feeling Fat

Many people report feeling fat, but the experience is exceptionally intense and frequent among those with eating disorders. This may be a consequence of their mislabeling certain emotions (like anxiety or depression), unpleasant physical states (e.g., feeling full, bloated, or sluggish), or body awareness (fueled by body checking, wearing tight clothes, and receiving comments on the body).

Feeling fat seems to be a consequence of patients’ longstanding and prolonged preoccupation with body shape. As patients often equate feeling fat with being fat (even if they are of average or low weight), it requires urgent attention.

Feeling fat is addressed by encouraging patients to ask themselves what else they feel when they feel fat and teach them to directly manage that emotion or circumstance.

Exploring the Origins of Overvaluation of Shape and Weight

Towards the end of treatment, patients should re-draw their self-evaluation schema to highlight any changes they have (Figure 2). If good progress has been made, the pie chart will feature new slices, and that representing shape and weight will be smaller. At this point, it may also be helpful to explore with the patient how their overvaluation of shape and weight developed and evolved. This strategy enables them to become consciously aware of how their eating problem arose, see how its early positive function (e.g., the feeling of being in control) may no longer be applicable, and distance themselves further from the eating disorder mindset.

References

Dalle Grave R & Calugi S (2018) Transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural theory and treatment of body image disturbance in eating disorders: A guide to assessment, treatment, and prevention. In: Cuzzolaro M. & Fassino S. (eds.) Body Image, Eating, and Weight. Cham: Springer.

Dalle Grave R & Calugi S (2020) Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders, New York, Guilford Press.

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z & Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A "transdiagnostic" theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther, 41, 509-28.