Perfectionism

Clinical Perfectionism and Eating Disorders

What to do when the two problems coexist.

Posted May 1, 2021 Reviewed by Pam Dailey

Key points

- Clinical perfectionism can significantly impair an individual’s life.

- Clinical perfectionism and eating disorders share a hyperfocus on achieving a goal.

- Treatment should de-emphasize achievement and encourage wider interests.

“I only got 8 out of 10 on my math test. I'm desperate because I made two mistakes. I must study more to stop making mistakes and improve my grade. I need to be getting a 10. What’s more, I have only lost 5 kilograms. I have to improve my dieting to lose more weight because I have to be the thinnest girl in school.”

Individuals with an eating disorder often display perfectionist traits, which are sometimes evident before the eating disorder begins (its onset). It is not clear whether perfectionist traits can make an eating disorder more difficult to treat or not, but there is no doubt that extreme clinical perfectionism can significantly impair an individual’s life. Because clinical perfectionism seems to maintain the eating disorder and negatively interfere with progress, it should be addressed by treatment.

Characteristics of Clinical Perfectionism

The key characteristic of clinical perfectionism is a dysfunctional self-evaluation scheme in which individuals judge themselves only or mainly on their ability to attain demanding and extremely high self-imposed standards in at least one important life domain, like school, sports, or relationships. They are not concerned about the consequences; the only thing that matters is that they reach their goal. This overvaluation of achieving is similar to the overvaluation of shape, weight, eating, and control (see this other Psychology Today post)—both are dysfunctional, fragile, and unstable ways of judging oneself.

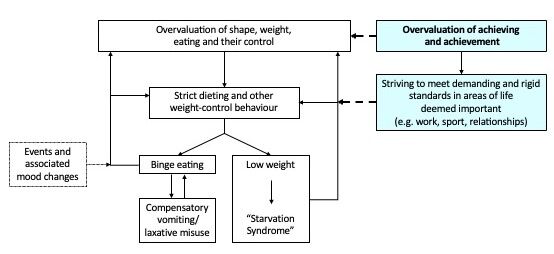

Clinical perfectionism has various harmful expressions that maintain the overvaluation of achieving, specifically (see Figure 1):

- Marginalization of other aspects of life

- Striving to meet demanding standards

- Re-setting the standards if the goals are met

- Performance checking and scrutinizing

- Procrastination and avoidance of performance

It has been noted that when a person has both clinical perfectionism and an eating disorder, the two problems interact. Specifically, perfectionist attitudes can become focused on the achievement of demanding standards in the control of shape, weight, and eating (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the tenacity in pursuing these standards increases, and there is a reluctance to change. In other words, clinical perfectionism intensifies aspects of the eating disorder and may complicate treatment.

When should clinicians suspect the presence of clinical perfectionism in a person with an eating disorder?

Clinical perfectionism should be suspected if a person with an eating disorder adopts dietary rules that are particularly extreme and rigid and slows down the treatment by getting lost in the details of the procedures to apply. Other common clues are if a person dedicates the majority of the day to studying or sports, despite significant others’ advice to reduce their commitment to this activity.

Table 1 reports a series of questions that may help to discern whether clinical perfectionism may coexist with the eating disorder.

Table 1. Questions that can help to understand if a person with an eating disorder has clinical perfectionism

Some people with an eating problem might be described as “perfectionists” because they set high standards and are constantly striving to achieve them. Would this describe you? What do others say about you?

- Do you set yourself higher standards than others? What do others think? In which areas of life do you set high standards (school, work, sports, music, etc.)?

- How important is it for you to work hard and do well?

- Do you spend a lot of time thinking about the goals you want to achieve?

- If you reach one of your goals, do you immediately set a higher one?

- Do you repeatedly check your performance and compare it to that of others?

- Are you afraid of not being able to achieve your goals?

- Do you avoid doing things for fear that your performance will not be good enough?

- Do you tend to judge yourself on the effort you put into trying to reach your goals and their achievement?

Addressing the Eating Disorder and Clinical Perfectionism

The broad form of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) is specifically designed to treat clinical perfectionism along with eating disorder.

Briefly, CBT-E treats clinical perfectionism via a two-prong strategy similar to that used to address the overvaluation of shape and weight. The dual aims are as follows:

- To increase the importance of other areas of life. The person is helped to choose and engage in activities in which their performance cannot be easily quantified. These may include activities such as reading novels, listening to music, or staying in touch with friends. In short, they will be asked to actively pursue other interests and thereby address their marginalization of other life domains.

- To reduce the importance of achieving and achievement. This is done by addressing performance-checking and performance-avoidance—in much the same way as body-checking and avoidance are addressed—as well as perfectionist standards and striving. The goal is to encourage patients to modify their standards, to make them less demanding and more flexible. They need to learn that “good is good enough.” The therapist helps them address their own individual combination of performance-checking behaviors, which may include self-assessing (checking personal performance), comparison-making (comparing personal performance with that of others), and reassurance-checking (asking others about one’s performance). It also addresses performance-avoidance (if applicable), which usually manifests by refusing to assess one’s own performance and avoiding external tests of performance, such as school tests, sports competitions, social events, singing in front of others, and so on.

Towards the end of therapy, the origins of the overvaluation of achieving are explored. The patients are helped to pinpoint events or circumstances that might have sensitized them to performance and contributed to their perfectionism. They are to identify any problem that remains and devise a specific, perfectionism-oriented maintenance plan designed to address any residual perfectionist attitudes and behaviors and to prevent relapse.

References

Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2021). Complex cases and comorbidity in eating disorders. Assessment and management. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Shafran, R., Bohn, K., & Hawker, D. M. (2008). Clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem and interpersonal problems. In C. G. Fairburn (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders (pp. 197-221). New York: The Guilford Press.

Shafran, R., Egan, S., & Wade, T. (2010). Overcoming perfectionism: A self-help guide using scientifically supported cognitive behavioural techniques. London: Little, Brown Book Group.