Relationships

How to Live With Other People (and Still Like Them)

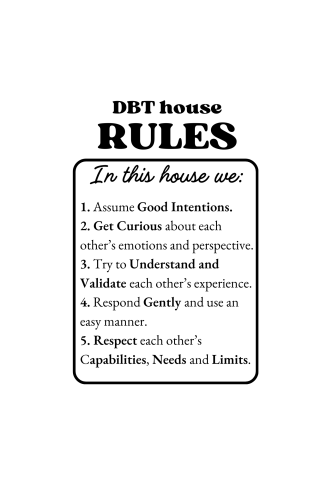

1. Assume good intentions.

Posted April 3, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Assuming that live-in partners, family, or roommates have good intentions makes it easier to stay skillful.

- Approaching housemates with curiosity about each other's needs and experiences transforms our interactions.

- Gentle humor and inside jokes reinforce that you and your household are a team taking on the world together.

- When you simply cannot assume good intentions, address the problematic behavior; don't ruminate about them.

This is Part I of a 5-part series on DBT house rules for successful relationships with live-in partners, family, and roommates.

Living with other people can be irritating. They do annoying things. They get crabby, bossy, or passive-aggressive. We often respond with defensive or avoidant behavior. Sometimes, the web of our relationships becomes so tangled that we aren't sure we even like these people anymore.

You can change that dynamic using the skills taught in dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT. Steve and John credit their wonderful loving marriage to the "DBT House Rules" they created from the skills they learned in DBT therapy. Steve explains, "John made a snarky comment about my neglect of the laundry pile I left on the couch for two days. My first thought was: He's so passive-aggressive. He doesn't understand the pressure I'm under. My first impulse was to yell: If it bothers you so much, why don’t you put it away?”

But Steve didn't lash out. Instead, he paused, took a deep breath, and looked at the "DBT House Rules" he and John had written out and taped on the refrigerator.

- In this house, we assume good intentions. Steve started by recognizing that his partner, John, is a good and kind person who doesn't like it when the house gets messy. Then Steve acknowledged his own defensiveness about not putting away his laundry. He had been secretly hoping that John would take care of it (as he often does.) Believing that John's comment was not an attack, but an expression of John's needs helps Steve manage his knee-jerk emotions.

- In this house, we get curious about each other’s emotions and perspective. Steve considers his partner a real human with needs of his own. He loves John deeply. With a tender voice, he asks, "I know you don't like it when the apartment gets messy. Is the laundry all that's bothering you? Or is there something else?" John shares that he feels neglected and lonely because Steve has been working so much. John expresses curiosity about Steve's experience. "How are you doing? I know you are under a lot of pressure right now."

- In this house, we try to understand and validate each other’s experience. Steve validates John's loneliness and shares his own feelings of disconnection. He feels guilty about working so much, which makes him pull away from John. Steve validates how difficult that must be for John.

- In this house, we respond gently and use an easy manner. Steve and John speak to each other with kindness when addressing complex topics. They nudge each other with gentle humor, making it easier to face challenging situations. Their inside jokes help them feel like a team taking on the world together.

- In this house, we respect each other's capabilities, needs, and limits. Steve commits to not leaving laundry on the couch. He starts putting the clothes away, even though he's tired. John recognizes Steve's fatigue and appreciates Steve taking immediate action. He offers to help with the folding. They spend the time together talking about each other's days.

Does this sound too good to be true? It is actually a true story. Every time Steve tells me about his relationship with John, I am flooded with awe. He notes, “I credit the DBT house rules. They remind us to speak to each other from a place of love instead of letting our conditioning and childhood defenses dictate how we treat each other."

As humans, we tend to react to the present moment based on our lifetime of painful experiences. We resort to our conditioning, especially when we feel hurt or angry. The DBT House Rules invite us to respond with kindness to the person standing before us in this moment, as they are right now.

This five-part series will explore the DBT skills behind each of Steve and John's five DBT House Rules.

Let’s start with “Assume Good Intentions.”

Spending lots of time with another person makes it easy to settle into casual irritability. We become reactive to any sign of selfishness or callousness, making it hard to live together. In DBT, every interaction is considered a transaction. Your behavior changes my behavior, and then my behavior changes your behavior. Going back and forth like this can escalate quickly.

Assuming good intentions helps us regulate our emotions and manage our behavior. Our side of any transaction is the only part within our control. If we stay skillful, we increase the odds of a positive outcome. When we are living with someone, life is much smoother when our interactions go well, and everyone feels cared for. Assuming good intentions helps us treat each other with kindness and care.

You may wonder: Why should I assume good intentions when someone else behaves badly? You may not like the other person’s behavior—that's OK. But if you believe they have malicious intent toward you, you may get afraid or angry. Your intense emotions may lead to impulsive behaviors and an inclination to shut down or lash out. Then, the other person may be triggered to escalate the situation. When everyone gets trapped in a cycle of reactivity, these interactions can destroy relationships.

By assuming good intentions, we stay connected to our wisdom (Wise Mind in DBT). Assuming good intentions helps us stay curious and emotionally regulated. With any luck, our conscientious, caring behaviors will change the tone of the interaction and lead to greater understanding. At the very least, it will help us move through the communication with our self-respect intact.

What about when you are sure the other person’s intentions are bad?

There is a dialectic here, meaning two opposing ideas can both be true.

Even though it’s more effective to assume good intentions, people sometimes have bad intentions. In that case, the DBT advice is: When you can't believe in good intentions, don't speculate about intentions at all. Just address the behavior.

Trying to figure out someone's intentions is like falling down the rabbit hole. To stay effective, you're better off thinking: I don’t know why this person is doing this, but I don’t like it.

You can then address the behavior using DBT skills without ruminating about the other person’s intentions. Many of the skills taught in DBT can help us cope with unpleasant interactions. The DBT house rules are just one set of strategies.

Sometimes, no matter how skillful you are, the situation doesn't improve. If you are in a situation where the other person's behavior is dangerous or violent, please seek the help and support of a licensed mental health professional or a social service program for people dealing with domestic violence. You don’t have to manage the situation alone.

In the next four posts, we will examine each of the other house rules and how they can improve relationships in your household.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: YAKOBCHUK VIACHESLAV/Shutterstock

References

The DBT skills taught here are based on the work of Dr. Marsha Linehan, creator of Dialectical Behavior Therapy.