Friends

Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends or Family?

An analysis of data from 107,597 dog welfare complaints is very discouraging.

Posted July 29, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

If dogs really are our best friends and family members, why do we view and treat them as we do?

"Puppies that were reported were more likely to be alleged to have experienced cruelty, lack of veterinary support, overcrowding, poor living and health conditions, and inappropriate surgery."

A recent study by Hao Yu Shih and his colleagues ("Breed Group Effects on Complaints about Canine Welfare Made to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) Queensland, Australia") provides valuable and detailed data on breed and cross-breed differences in the reporting of welfare complaints and differences in the types of complaints the RSPCA received. The essay is available for free online and is a pretty easy read.

What caught my eye was the huge number of welfare complaints—129,036—that were reported over a 10-year period, of which 107,597 were analyzed. It's difficult to know if these data apply to locations other than Queensland, but a web search shows that numerous locations have formal procedures for reporting welfare complaints, so it's reasonable to assume that dog neglect and cruelty are important welfare and social issues.

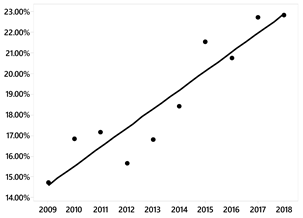

In another essay also by Hao Yu Shih and his colleagues called "A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare," we read, "The number of complaints received each year increased by 6.2 percent annually." Figure 2 in this essay shows the patterns of various complaints that were received over the 10-year period.

On average, complaints about overcrowding, tail-docking, and dogs not receiving sufficient food or water tended to decrease; however, complaints about poor living conditions (graph below) and leaving dogs in hot cars showed positive linear trends, and complaints about cruelty showed an increase from 2016-2018. Complaints about dogs not receiving proper veterinary treatment, being abandoned, and not getting proper shelter fluctuated over the 10-year period, and puppies suffered more than older dogs.

After reading the above essays, what came to mind was the meme-like myth that claims dogs are our best friends. They're not. (For more, see "Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends?")

Many people's contact with dogs is limited to "homed dogs," often only "homed Western dogs." They don't realize that it's been estimated that around 85 percent of dogs in the world, perhaps as many as 700-800 million individuals, are pretty much or totally on their own.1 As a woman named Elena wrote to me, "Dogs are our victims, our captives, yet we often claim they're our best friends and family members. How do we get away with this?"

One way, of course, is that all sorts of media and some researchers talk about dogs as if there is a "universal dog" who can be used as an ambassador for all dogs who supposedly are just like them. Research, citizen science, and common sense clearly show there is no "the dog."

Dogs come in numerous sizes and shapes and display a wide spectrum of individual personalities, even among littermates and other siblings, to which we must pay close attention when trying to give them the best lives possible in a human-dominated world. (See Unleashing Your Dog.) Elena is correct when she asks how do we get away with claiming dogs are our best friends or family members as if there's some wide-ranging database that supports this idea.

In addition to the data offered by Hao Yu Shih and his colleagues, here are some reasons why we need to revise our thinking about our relationship with dogs and the language we use.

- Complaints about different sorts of abuse and cruelty are on the rise in many different locations. Reading about this sort of violence is very difficult, but sadly, it's a real phenomenon that needs to be understood in order to put an end to it once and for all.

- Dogs are considered property we own in all legal systems with which I'm familiar. (See "Dogs may be man’s best friend, but they’re just property: judge.")

- We knowingly breed some dogs who we know will suffer because of human tastes, many of whom have short lives and can't breed or give birth on their own. Bioethicist Jessica Pierce notes that in this sort of selective human-centered breeding, we're purposely introducing malware into some dogs. (See "'Why in the World do People Make These Types of Dogs?'" and "The Lifespan and Health Conditions of French Bulldogs and Labrador Retrievers.")

- Despite data to the contrary, punishment-based training still is widely used. (See "Science Shows Positive Reward-Based Dog Training is Best" and "'Bad Dog?' The Psychology of Using Positive Reinforcement.")

- For a variety of reasons, we spread many myths about dogs, as if they're the model animals to whom we should aspire. These myths become memes. Myth, metaphors, and memes about who dogs supposedly are short-change them. (See "'Why Do People Make Up Myths and Other Stuff About Dogs?'")

- Many people's contact with dogs is limited to "homed dogs," often only "homed Western dogs," so far too many discussions of "the dog" refer to only a tiny fraction of dogs who live on our planet. Nonetheless, abuse and cruelty are far too common, even in this very small cohort.

We need to change the language we use to refer to dogs and stop using misleading language.

"'Pets are part of the family!' is a mantra of the media, the pet industry, and even the academic veterinary literature. You’ll often see the figure, '90 percent of pet owners consider their pet part of the family.'... Whenever you hear the 'pets are family,' think of it not as a fact, not as the way it is, but as a moral and practical ideal." — Jessica Pierce, "Are Pets Really Family?"

Clearly, we need to get a firm grip on what life is like for countless companion and other dogs. I prefer to believe that most people who choose to share their homes and hearts with dogs have the best intentions in mind—they're not necessarily "bad people."

However, many people who choose to live with dogs aren't dog literate, or fluent in dog, or perhaps haven't done the deep thinking that's required before bringing a dog into their lives. (See "New Study Shows Importance of Understanding Dog Behavior.") People often remark that nature is very cruel, and I like to say this isn't so, but some humans are.

When some people say they love their dogs as best friends and are glad they're family members, I often think to myself, I'm glad they don't love me or consider me their best friends or family members. In many situations, I don't doubt their feelings, but their actions surely don't reflect what they say they feel. Jessica Pierce notes, "contrary to the media, many, many people don’t consider their animals as family." Being a "family member" is a sound bite from a limited survey conducted by the American Pet Products Association done on people who purchase pet products.

There's nothing wrong with saying that dogs aren't necessarily our best friends or family members as there's ample information showing they're not, and we should be very careful when saying this or stop saying they are as if all dogs fall into these categories. Saying dogs are our best friends or family often leads us to be complacent, to think that they're being treated with kindness while not taking their needs seriously or paying attention to obvious and more subtle forms of cruelty. Jessica Pierce wrote about a woman she met at a park who gushed about how much her dog had been a part of her family, yet she had to get rid of him when she moved.

The same goes for the erroneous claim that dogs love us unconditionally. They don't. Making sweeping statements that all (or even most) dogs unconditionally love us is an inaccurate portrayal of what we really know from many studies of dog-human relationships and dog behavior. (See "Dog Bites: Comprehensive Data and Interdisciplinary Analyses" and "Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends?")

Facts show that not everyone considers dogs to be friends or family, and dogs are rather picky themselves. We owe it to dogs to learn more about the various relationships they form with humans and more about who they are and what they feel. We need to better understand their perspective and what they need from us and how they sense their world.

As we learn more about dog-human relationships and dog behavior, there will be many valuable lessons about how to form and maintain the closest and best possible reciprocal social bonds given who an individual dog is and who the humans with whom they interact are, and it will be a win-win for all.

Stay tuned for further discussions on these and other topics centering on dogs and humans and what's really going on between them.

Note

1 It's very difficult to estimate how many dogs there are in the world. One reliable estimate puts the number between about 750 million and 1.2 billion. Some claim we can't generalize from the Western world to other locations. The main point is that a very large number of dogs are pretty much or totally on their own.

According to an essay by Sundra Chelsea Atitwa, updated in January 2018, titled "How Many Dogs Are There In The World?", the global population is estimated to be around 900 million. In this piece, we're told the World Health Organization (WHO) "estimates the total number of stray dogs to be about 200 million, and the total population of free-range dogs to make up about 75-85 percent of the global dog population."

A lot also hangs on definitions of different classes of dogs. In Atitwa's essay, "Free-range dogs are those that are not contained. They can be stray dogs, federal dogs, wild dogs, street dogs, and village dogs. Stray dogs are differentiated from feral dogs in that they were socialized before becoming free-ranging, whereas feral dogs are raised without human socialization."

Facebook image: Marco Ossino/Shutterstock