Authenticity

Becoming a Subject of Your Own Desire

Too many women want to be wanted instead of following their heart's desires.

Updated July 13, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Twenty-three years ago, while browsing in the bookstore of an institute in San Francisco where I was a freshly-arrived graduate student, a title in the new releases section suddenly grabbed my attention: Women and Desire: Beyond Wanting to be Wanted (Polly Young-Eisendrath, 1999). A sense of recognition washed over me, and I proceeded to devour the book over the next 24 hours as it contained so much nutrition that I’d been hungering for. The book articulated what I, and so many women I knew, were experiencing but could not quite name.

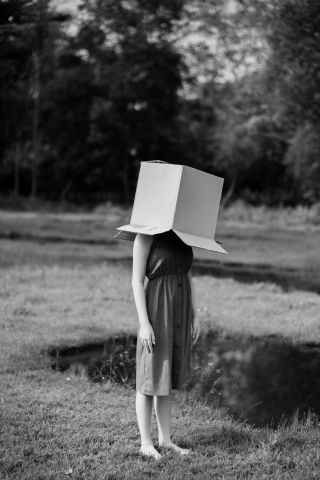

The author, a psychologist and Jungian analyst, argued that women are alienated from their desire, from their own wanting. Instead of moving outward toward the world based on their desire, they channel their energy toward wanting to be wanted by others. Precious life energy that might be channeled toward their longings becomes rerouted toward the project of cultivating a pleasing and attractive image, thereby fueling the desire of others. In the process, women become “trapped in images” and sacrifice authenticity, self-sovereignty, and the capacity to be subjects of their own desire:

"Wanting to be wanted is about finding our power in an image rather than in our actions. We try to appear attractive, nice, good, valid, legitimate, or worthy to someone else, instead of discovering what we actually feel and want for ourselves. In this kind of conscious or unconscious arrangement, other people are expected to provide our own feelings of power, worth, or vitality, at the expense of our own authentic development. We then feel resentful, frustrated, and out of control because we have sacrificed our real needs and desires to the arrangements we have made with others. We find ourselves always wanting to be seen in a positive light: the perfect mother, the ideal friend, the seductive lover, the slender or athletic body, the kind neighbor, the competent boss. In place of knowing the truth of who we are and what we want from our lives, we become trapped in images." (Polly Young-Eisendrath, 1999)

Discovering that book in my 20s was clarifying. I knew I had a lot of work to do to withdraw energy from the project of attempting to be the object of desire, the project of chronically attempting to be chosen by others rather than guided primarily by my own choosing. I knew I needed to take more responsibility for my own desire if I was going to live life more fully on my own terms.

Yet I also knew that the predicament I was in wasn’t my fault, nor was it a natural aspect of my development as a woman. It was a result of growing up in a male-dominated, patriarchal culture that fears female self-sovereignty, female power, and female desire. As the blinders fell away I saw more clearly how much precious time I’d wasted on what amounted to a lie: that being desired equals being happy, fulfilled, and loved. (I recommend model/actor Emily Ratajkowski’s memoir My Body as a detailed description of the consequences - chronic shame, dissociation, self-alienation - of orienting one’s life toward the goal of becoming the object of desire.) I was ready to yank that lie out by the roots, grieve lost life energy, and begin planting something new in its place.

Over the years since, I have attempted to take up my desire very intentionally: listening closely to it; working to untangle it from the desires of my parents, peers, and the overculture; following my desires in small and larger ways (and in so doing learning about my limits and cultivating a personal ethical code); and dealing with the consequences of sometimes displeasing others in the process. It’s a work in progress—a messy and radically imperfect work in progress.

Today I work as a clinical psychologist, providing psychotherapy to adult women. I’d like to report that women’s relationship with desire has changed significantly over the last 23 years, but from my therapeutic perch it doesn’t appear to be the case. So many female clients of all ages tell me the same thing, using different words, though the message is essentially the same: “I don’t know what I want or even how to know what I want.” “I know vaguely what I desire but I’m terrified to follow it.” These women have been investing so much of their energy in appearing beautiful, helpful, successful, or “perfect” – perfect mom, perfect romantic partner, perfect daughter (even women in midlife and beyond struggle with this), perfect employee and colleague, etc. – at the expense of knowing themselves from the inside out and directing the flow of their desire outward toward their projects in the world. They are caught in the matrix of wanting to be wanted.

The energy meant to flow outward gets thrown back on themselves in an endless self-referential loop that ultimately goes nowhere. And given factors such as the hyper-influx of social media and pornography into the larger culture, it’s not difficult to argue that the problem we’re discussing, though its specific features may have changed, has gotten worse overall.

It is worth clarifying that is developmentally appropriate, especially during adolescence, to seek validation and approval from parents, peers, romantic partners, and authority figures. We come to know ourselves in the context of our relationships with others and their responses to us. It is also worth clarifying that it can be deliciously pleasurable to experience the desire of other people; that’s not an unhealthy experience in and of itself. It is when the seeking of validation becomes compulsive in quality – rather than a lighthearted or playful endeavor; when people get stuck in the need for that validation; when the desire to be desired becomes a central motivator for one’s actions and one keeps reaching for the sugar high of approval and validation rather than real sources of nutrition that there’s a problem worth addressing. A final note worth clarifying: Many men in this culture are also ensnared in the net of wanting to be wanted, while some women appear to have escaped the net almost entirely.

Problems that tend to afflict women more than men are often minimized or written off as superficial. We should not minimize this problem. Wanting to be wanted as a central motivating force amounts to a colonization of the psyche and a usurping of the life force that could instead be channeled toward the creation of a more connected, meaningful, juicy, LIT UP existence.

The project of subjectifying our desire is not a superficial project with narcissistic aims. Quite the opposite. Reorienting oneself from object to subject of desire involves healing narcissistic wounds – wounds resulting from growing up in the context of a patriarchal, sexually-objectifying culture that leave so many women with an injured sense of self. Progressively subjectifying our desire shifts the compass that orients our actions from the outside (“What will they think of me?”) to the inside (“What do I want?”). We learn to tune into an inner compass, move outwards toward the world from that home base, and, in turn, experience more agency, vitality, and freedom. At the end of the day, isn’t that what most people truly want?

A blog post can only serve as a mere suggestion or invitation, rather than presenting a sophisticated analysis of an issue. Desire is complicated. Psychoanalytic, religious, and philosophical traditions have attempted to understand it, harness it, arouse it, extinguish it, or crack its code. But we needn’t get bogged down in theory to engage in a meaningful inquiry into desire. If you see value in taking up your relationship with desire more consciously, do it. Do whatever it takes to tend the inner fire.

Know your own heart, and abide by it.