Health

The College Student Mental Health Crisis (Update)

What's behind the rise in reported problems?

Posted November 18, 2018

In 2014, I wrote a series on the college student mental health crisis, what may be causing it, and what we might be able to do about it. I receive more inquiries and requests for interviews about this topic than anything else. Because I have explored this issue in more depth, I decided the time was right for an update.

What, exactly, is the “college student mental health crisis?” It refers to the fact that (a) significant numbers of college students experience mental health problems (between a quarter and a third at any given time), and (b) over the past 15 to 20 years, we have seen a dramatic increase in the demand for mental health services on college campuses.

To give one example of the numbers we are talking about, last month a research report came out that found rates of “past year treatment" had risen from 19% in 2007 to 34% in 2017. In addition, students with lifetime diagnoses increased from 22% in 2007 to 36% in 2017. The trend lines in these categories had been moving up steadily through the 1990s. Here, then, is the nutshell summary of the crisis:

In the 1980s, at any given point, perhaps 1 in 10 college students could be readily characterized as needing/wanting/using some form of mental health treatment. Now that number is 1 in 3, with trend lines rising.

Here is the $64,000 question about these numbers: What is really going on? Are we seeing an “epidemic” of mental illness racing through the country? Or are we seeing a shift in attitudes, definitions, and the expectation of, availability of, and willingness to seek mental health treatment? My opinion is that the primary cause is a change in attitudes and use, with an important secondary cause being an actual increase in emotional fragility and distress (and thus an increase in anxiety and depressive conditions).

The first point is certainly true. That is, there have been major changes how people think about mental health and major increases in folks’ willingness to use mental health services. This attitude change is clearly one major reason for the difference. Some scholars argue that attitude change and a willingness to seek treatment is the only reason for the shift. In this interpretation of the crisis, people were suffering with mental illness in the 1980s and '90s at similar rates as they are now, but they were much less likely to talk about their problems openly and much more reluctant to seek treatment (perhaps because of stigma) or had less knowledge or access to do so.

Fellow PT blogger Todd Kashdan, a psychologist for whom I have much respect, recently made this case. He acknowledged that students are in some ways more sensitive and prone to anxiety, but argued against an epidemic of mental illness. He offered data from three sources that suggest that mental health problems have not gotten worse. For example, a major National Co-morbidity Study found that just about 30% of people surveyed between 1990-1992 had a mental health condition and almost the exact same percentage was found in those surveyed between 2000-2002. However, despite similar base rates, the numbers of folks who sought treatment had almost doubled in the same period. Ronald Pies has made a similar argument, namely that what has changed is treatment-seeking behavior, rather than actual levels of mental illness.

Although their arguments are important, the data they report are not the only data on this topic. I see a number of indicators that things have actually gotten worse, especially when we look at this generation and data in the last decade.

Some general population level data do suggest fairly stable trend lines (such as those reports offered by Kashdan and Pies). At the same time, there are some data suggesting general levels of well-being and happiness in the country as a whole are decreasing somewhat. It is clear that we are witnessing disturbing trends in some specific populations in the U.S. For example, we have definitely seen substantial increases in rates of suicide, substance misuse, and depression in certain demographics, such as middle age, lower-class whites.

Trend lines in adolescents and young adults also show evidence of increases in psychopathology. Jean Twenge has been tracking cohort data carefully and has found significant changes in stress, depression and anxiety. The NIMH has found an increase in the frequency of Major Depressive Disorder diagnoses in adolescents. The rate was 7.9% in 2006 and jumped to 12.8% in 2016. That is almost a 50% increase, based on good diagnostic assessments (not service utilization). The suicide rate for adolescents and young adults (per 100,000 people) also has seen a jump. It was 9.9 in 2006 and 13.5 in 2016. Again, about a 50% increase in the past decade. These are substantial changes and are not self-report or treatment-use data.

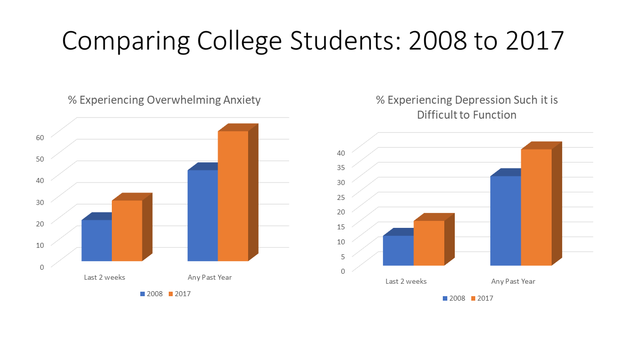

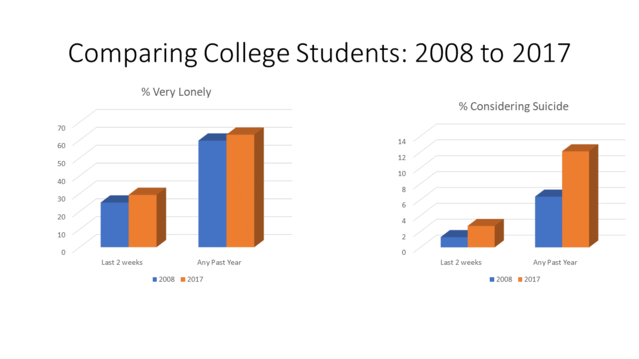

A similar pattern is found if we compare college student self-report data on feeling distress. The American College Health Association puts out an annual report based on large surveys of college students. I pulled scores from 2008 and compared them to scores in 2017 on feeling overwhelming anxiety, depression, loneliness, and suicidal ideation, both in the past two weeks and in the past year.

As depicted in these graphics, we see a substantial increase in rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, and some increase in loneliness.

In sum, there are a number of data pointing to actual increases in rates of mental illness/distress. The strongest data point to this being a generational phenomenon with increases in children, adolescents and young adults emerging since the 2000s. I should comment here that this is not something that has to do with college students per se. That is, there is not much reason to suppose that college students would be worse off in terms of mental health than those who don’t go to college.

The take-home message is this: The college student mental health crisis refers to the massive increase in treatment-seeking in college students. Whereas perhaps 10% were self-identified and seeking treatment in the 1980s, now approximately 33% are. This massive rise is likely a function of both more accepting attitudes about reporting distress and seeking and receiving treatment, and actual increases in stress, anxiety, and depression and other related problems.

There are no signs of this abating. Indeed, when I spoke about the trend with Dr. David Onestak, the Director of the Counseling Center at James Madison University, he made the point that we should no longer call it a "crisis" because it has been going on for more than a decade and does not appear to be slowing down. Rather, this distressing state of affairs seems to be the “new normal.”

My next post will be on why things have changed and will offer some resources for what we should be doing about it.