Health

Unexpected Findings Cause Scientists to Rethink Probiotics

Consuming commercial probiotics can have negative consequences in some cases.

Posted September 2, 2018

In recent months, surprising evidence has emerged that commercially available probiotics containing "good bacteria for your gut microbiome" may not be the panacea most of us have come to believe.

A June 2018 study, "Brain Fogginess, Gas and Bloating: A Link Between SIBO, Probiotics and Metabolic Acidosis," reported that in some people (for reasons that are not fully understood) probiotic use resulted in a higher prevalence of “small intestinal bacterial overgrowth” (SIBO) and “D-lactic acidosis," which was correlated with extreme belly bloating and brain fogginess. (For more see, “In a Brain Fog? Probiotics Could Be the Culprit.")

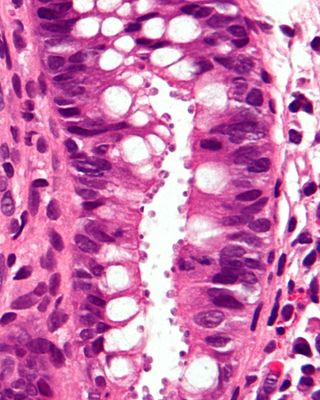

Now, a new animal study published online August 31 reports that mice who consumed a commercial probiotic intended for human consumption experienced more severe infections linked to the intestinal parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. This paper, “Probiotic Product Enhances Susceptibility of Mice to Cryptosporidiosis,” was published in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Cryptosporidiosis was linked to about 48,000 deaths worldwide in 2016 and caused the loss of more than 4.2 million disability-adjusted life-years, according to a meta-analysis study funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and published in The Lancet: Global Health. Currently, there are no specific drugs or vaccines that effectively treat or prevent cryptosporidiosis. The authors of this analysis conclude, “Interventions designed to prevent and effectively treat infection in children younger than five years will have enormous public health and social development impacts.”

What makes the latest study on the potential backlash of probiotic use especially noteworthy is that when Bruno Oliveira and Giovanni Widmer of Tufts University designed their study, they expected that the influence of probiotics and so-called "good bacteria" on microflora would make mouse intestines more resilient to infection. But, the opposite outcome occurred. On average, Oliveira and Widmer unexpectedly found that mice exposed to Cryptosporidium and given probiotics developed more severe intestinal infections. On the flip side, a control group of mice exposed to the same intestinal parasite that didn’t consume probiotics experienced less severe infections.

For this experiment, the native intestinal microbiota of mice was depleted by orally administering an antibiotic. Humans and mice are both more vulnerable to intestinal infections after a round of antibiotics. Just like doctors often recommend probiotics to reboot “good bacteria” in the gut after taking antibiotics, the mice who had received antibiotics were given a probiotic designed for human consumption diluted in their drinking water.

Despite an outcome that contradicted their original research hypothesis, the results of this study do provide first-of-its-kind evidence that it may be possible to develop more finely-tuned probiotics that could mitigate cryptosporidiosis. Before this research, it was unknown if Cryptosporidium growth in the gut could be influenced by probiotics in the diet.

"The goal is now to find a mechanistic link between microflora and Cryptosporidium proliferation, and ultimately design a simple nutritional supplement which helps the body fight the infection," senior author Giovanni Widmer, who is a professor of infectious disease and global health in the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, said in a statement. "Identifying specific mechanisms that alter pathogen virulence in response to diet may enable the development of simple pre- or probiotics capable of modifying the composition of the microbiota to reduce the severity of cryptosporidiosis.”

Oliveira and Widmer sum up the importance of their findings, “The results show that Cryptosporidium parvum responds to changes in the intestinal microenvironment induced by a nutritional supplement. This outcome paves the way for research to identify nutritional interventions aimed at limiting the impact of cryptosporidiosis.”

Beyond Probiotics: Genetic Engineering Could Lead to Synthetic Microbiome

There are over a thousand different strains of bacteria commonly found in the human gut. Scientists are only beginning to understand how different colonies of gut microbiome communicate with one another. That said, pioneering research by a Harvard consortium that includes scientists from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women's Hospital are working to create a “synthetic microbiome.”

In a mouse model, this genetic signal-transmission system has shown the ability to send and receive signals on the overall density of the gut’s bacterial colony and regulate the expression of specific genes within microbiome colonies. These potentially groundbreaking findings were published August 20 in a paper, “Quorum Sensing Can Be Repurposed To Promote Information Transfer between Bacteria in the Mammalian Gut.”

The authors sum up the main takeaway of this research in the study abstract: “The gut microbiome is intricately involved with establishing and maintaining the health of the host. Engineering of gut microbes aims to add new functions and expand the scope of control over the gut microbiome. To create systems that can perform increasingly complex tasks in the gut, it is necessary to harness the ability of the bacteria to communicate in the gut environment. This study provides a basis for further understanding of interbacterial interactions in an otherwise hard-to-study environment.”

"Ultimately, we aim to create a synthetic microbiome with completely or mostly engineered bacteria species in our gut, each of which has a specialized function (e.g., detecting and curing disease, creating beneficial molecules, improving digestion, etc.) but also communicates with the others to ensure that they are all balanced for optimal human health," corresponding author Pamela Silver said in a statement. Silver is a founding member of the Department of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School and Principal Investigator at the Silver Lab.

In closing, founding director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, Donald Ingber, put his team's work and the overarching importance of advanced research concerning gut bacteria in context, "The microbiome is the next frontier in medicine as well as wellness. Devising new technologies to engineer intestinal microbes for the better while appreciating that they function as part of a complex community, as was done here, represents a major step forward in this direction."

References

Bruno C. M. Oliveira and Giovanni Widmer. "Probiotic Product Enhances Susceptibility of Mice to Cryptosporidiosis." Applied and Environmental Microbiology (First published online: August 31, 2018) DOI: 10.1128/AEM.01408-18

Suhyun Kim, S. Jordan Kerns, Marika Ziesack, Lynn Bry, Georg K. Gerber, Jeffrey C. Way, Pamela A. Silver. "Quorum Sensing Can Be Repurposed To Promote Information Transfer between Bacteria in the Mammalian Gut." ACS Synthetic Biology (First published online: August 20, 2018) DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00271

Satish S. C. Rao, Abdul Rehman, Siegfried Yu, Nicole Martinez de Andino. "Brain Fogginess, Gas and Bloating: A Link Between SIBO, Probiotics and Metabolic Acidosis." Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology (First published: June 19, 2018) DOI: 10.1038/s41424-018-0030-7