Joe Forgas is a prominent social psychologist who has spent the last couple of decades studying what might seem like a depressing topic: Sadness. Has studying sadness made him miserable? Not at all. In fact, as Forgas argues in this month’s issue of Current Directions in Psychological Science, he and his colleagues have discovered something surprising: Being in a bad mood can improve your thinking, your motivation, and your social life! On the other side of the coin, being in a happy mood can sometimes have unhappy consequences on the way you think, and on the way you act toward others.

Here are 7 exemplary findings suggesting some benefits of sadness over happiness:

1. Improved memory. People in one study were tested for their memory of the details of a shop they just visited. Those who visited the shop on gloomy cold days remembered more details than those who visited on a sunny warm day. In another study, the researchers found that eyewitnesses to an altercation were less likely to be have their memories distorted by a misleading line of questioning if they were sad, whereas happiness made them more inclined to misremember. Forgas believes that these findings reflect the fact that sad people are more likely to be attuned to their environments, whereas happy people are more likely to just “go with the flow.”

2. More accurate judgments. There is a classic finding in experimental psychology called the “primacy effect.” If you read two paragraphs about a fellow named Jim, and the first one makes Jim sound like a quiet and shy introvert, whereas the second one focuses on some of his extraverted tendencies, you will remember him as an introvert, and reinterpret the extraverted behaviors as atypical. If you read the same information in the reverse order, however, you will remember him as an extravert. Forgas found that a happy mood magnified that bias, but negative mood erased it, again suggesting that the sad subjects make clearer judgments.

3. Reduced gullibility. People in a negative mood are more skeptical in numerous ways, less likely to be misled by urban myths, and more likely to detect someone else being insincere.

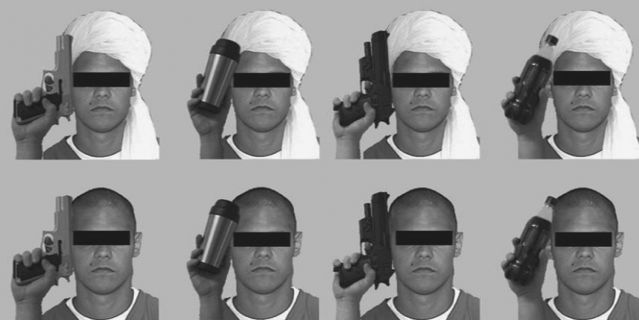

4. Reduced stereotyping. In one experiment, Forgas and his colleagues asked subjects to play a “shoot-don’t shoot” game, in which your goal is to play a cop whose task is to shoot any bad guys holding guns, but to hold your fire when the target is holding a soda can or cell phone. The task was made more complicated by having half the targets wearing Muslim headgear (a heuristic cue for threat at a time of high conflict in the Middle East). (see the photo for the pictures they used).

There was a general tendency to shoot more at the fellows wearing the Muslim headgear, and that tendency was magnified among the people who were feeling happy (so being happy doesn’t always make you nicer).

5. Motivational benefits. People in a sad mood are more likely to persist at a difficult task, and less likely to self-handicap, than are people in a neutral mood. Happy people, on the other hand, are more likely to quit a difficult task, and to handicap themselves by drinking a beverage that can hurt their performance.

6. Increased politeness. Compared to people who have just watched a happy film, people who have just watched a sad film are more likely to make a request in a polite and nicely elaborated way. Happy people are less attuned to their audience.

7. Increased fairness. People in another experiment were asked to play either a “dictator game” (you get $10, for example, and can divide it any way you want between yourself and another player) or an “ultimatum game” (you get to propose how to divide the $10, but the other player can say “no way” if you decide to keep $9 for yourself, and offer her only $1, in which case neither of you gets a dime). Sad people made more reasonable and generous offers in these economic games, whereas happy people were, once again, more self-centered.

From all his research, Forgas concludes that: “These findings stand in stark contrast with the unilateral emphasis on the benefits of positive affect in the recent literature as well as in popular culture. It is now increasingly recognized that positive affect, despite some advantages, is not universally desirable.”

He does note a couple of important qualifications. Most critically, these findings involve mild everyday negative moods, not intense, prolonged, and debilitating clinical levels of depression.

Forgas's program of research adds to an emerging literature that stresses that negative as well as positive moods and emotions all serve useful functions. As such, Forgas notes, it can be self-defeating to spend one’s time in the unrelenting pursuit of giddy levels of euphoria. (I’ve discussed related issues in a couple of earlier blogs: What's so good about negative feedback? And If You Pursue Happiness, You May Find Loneliness).

So the next time you find yourself feeling mildly sad, instead of beating yourself up about it, or running to the medicine cabinet for your psychotropic meds, you might take a Zen perspective: Your unconscious mind may be telling you it’s time to think carefully about whatever you’ve been doing, step on the brakes, and more carefully plan out an alternative strategy.

Douglas T. Kenrick is the author of Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature. Now available in paperback (and in German, Chinese, and Korean!). His new book: The Rational Animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think (coauthored by Vlad Griskevicius) was just released.

Related blogs:

What's so good about negative feedback? Zen and the Art of Embracing Rejection.

If You Pursue Happiness, You May Find Loneliness: Some Sad Facts About Happiness

Reference:

Forgas, J.P. (2013). Don’t worry, be sad! On the cognitive, motivational, and interpersonal benefits of negative mood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 225–232.