Aging

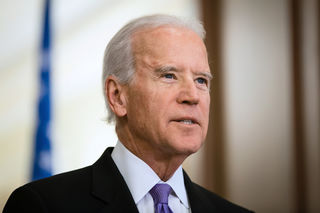

Is Joe Biden Too Old to Be President?

Joe Biden's age is an issue in his run for president. How much should it matter?

Posted July 9, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

In the current race for the Democratic presidential nomination, Joe Biden’s age has been a frequent topic. That’s not surprising. He’s 77 years old now and will turn 78 a few days after the 2020 presidential election. That would make him by far the oldest person to be elected to the office.

So, he’s old, relative to previous candidates. But is he too old? Should his advanced age be disqualifying, given the demands of the office? There is a lot of theory and research on adult development that can illuminate the answer to these questions.

There is a long history in Western societies of portraying late adulthood as a time of pathetic decline. When the Greek philosopher Solon laid out a stage theory of human development about 2,500 years ago, all that was left for the last stage, ages 63–70, was to “make preparations for a not untimely death.”

In the 12th century, Dante described four life stages, the last of which was “senility,” from age 70 onward.

Shakespeare, in the 16th century, offered one of the most caustic views of all, through his character Jaques in As You Like It, who depicted seven life stages, culminating in old age: “Last scene of all / That ends this strange eventful history / Is second childishness and mere oblivion / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Perhaps this history still influences our perceptions of late adulthood. Many studies in Western countries have found that older adults often encounter ageism. Attitudes toward older adults are generally more negative than toward younger adults in a variety of respects, from competence at work to physical attractiveness. Older adults applying for jobs are often assumed to be on the decline and lacking in cognitive sharpness and physical stamina. Social psychology studies that present participants with a hypothetical situation—misplacing an object, for example—find that when the person in the scenario is described as young, participants assume the mistake is due to a temporary state (“he had a lot on his mind”), whereas when the person is old the mistake is assumed to be due to irreversible decline (“he’s going senile”). Even many older people believe many stereotypes of aging, and when they do, their physical and mental health suffers.

Of course, it's not like these stereotypes are completely invalid. All of us are subject to primary aging, the inevitable biological aging processes that take place in all members of the human species and in all living organisms.

A great deal of research on late adulthood documents the declines in functioning that occur as part of reaching old age. The senses become less acute. Risks of a wide variety of health problems rise steeply, and even performing routine activities of daily living becomes challenging for many. Cognitive abilities wane, and the possibility of dementia rises. Overall, Solon and Shakespeare were not all that far off the mark.

Does this mean we should kiss off Uncle Joe as too old? Not so fast. Although primary aging occurs for us all, it doesn’t occur to all of us at the same pace or to the same degree. At every age from 60 onward, there is immense variability among adults in their physical, cognitive, and mental health. Gerontologists use the concept of functional age to signify the actual competence and performance of older adults, irrespective of their chronological age. Although chronological age and functional age are correlated, some 78-year-olds may have a younger functional age than the typical 60-year-old because their physical, cognitive, and social functioning is better. Another relevant concept is successful aging, which recognizes that many people maintain a high level of psychological functioning well into late adulthood.

Joe Biden seems to have a much lower functional age than most of his septuagenarian peers. After all, he served as an engaged and valuable vice-president well into his early 70s. Running for president requires a great deal of physical energy and cognitive acuity, for example in debates, when responses to moderator questions and to other candidates must be swift and the possibility of a catastrophic blunder looms large. The campaign is still early, but so far he has been a veritable model of successful aging and right now he remains the leading candidate for the Democratic nomination.

Let’s not forget that there are also some advantages that come with age and may make for better performance as a candidate and as president. Expertise is the superior skill that comes with long-term experience in a specific field and provides the basis for superior performance and achievements. There is no one in the Democratic field who has expertise in political life and government office that comes anywhere near to Joe Biden.

One can also hope that with age comes wisdom. So far psychology has struggled to come up with an effective way of measuring wisdom. Nevertheless, throughout the world positions of authority that require wisdom are often filled by persons in late adulthood—from tribal leader and shaman to prime minister, CEO, and supreme court justice. In one study that asked adults of various ages to name public figures high in wisdom, most selected older adults, with a median age of 64. If Joe Biden is elected president in 2020, we can all hope that he will bring his accumulated wisdom to the many influential decisions a president makes.

In sum, growing older can and usually does have some detrimental effects, but not on everyone to the same degree, and there are positive consequences of aging, too. Whatever his strengths and weaknesses may be as a candidate for president, Joe Biden deserves to be judged on them and not on his age alone.