Relationships

Love What You Do, Pour Your Heart Into It and You'll Succeed

Christopher Bergland shares his story of becoming a Guinness Record athlete.

Posted December 31, 2015

I was born in 1966 on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. When my parents' marriage began unraveling in the late 1970s, my sisters and I were sent off to various boarding schools in New England. At the time, I think my mom thought that boarding school would offer refuge from the "War of the Roses" taking place at home. My father was probably impressed by the potential prestige of prep school. Unfortunately, my boarding school experience was a living hell that pushed me to the brink of self-destruction.

I attended a conservative boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut. JFK was an alumni of the school. On some levels, I think my dad thought that a diploma, and the social networking power of Choate, would be my passport for becoming part of the "old boys' club." There was one problem. I'm gay. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic was decimating the gay community. Homophobia and the fear of HIV was at an all-time high. As a gay teenager at prep school in Connecticut, I was ostracized and made to feel 'less than' by both my peers and the administration. It sucked.

Coming of Age and Coming Out

As a gay high school student in the early ‘80s, I was stereotypically unathletic. I wasn't into sports, and was bullied by my dean, who was also the coach of the football and baseball teams, for being a “sissy.” As part of my coming out process, I became obsessed with proving to my dean (and the world) that just because I was gay, it didn’t mean that I lacked mental toughness, stamina, or grit. I knew from watching powerful women succeed, that I could be a thoughtful and sensitive human being, and simultaneously be a tough-as-nails trailblazer. Like most people who have felt marginalized—or treated like second-class citizens by the powers that be—I developed a spine of steel as a teenager, but have always felt empathetic to the underdog.

I started running when I was 17 and it changed my life. As an adolescent, I had no desire to enter races or compete in athletics. In 1983, the Walkman had just been invented, which was a godsend. I was able to make mixed tapes with anthems such as “Flashdance... What a Feeling,” “Blinded by the Light,” and “Holiday” which took me to another place when I ran. Running became a sanctuary and an escape from the homophobia and hatred I experienced in the real world during the ‘80s.

Also, as someone who identified as a “98-pound weakling” growing up, athletics gave me much needed confidence and chutzpah to seize the day in all aspects of my life. I continued running in college, but my alma mater, Hampshire College, is a non-traditional school with no tests, grades, or organized sports (except for ultimate Frisbee).

When I moved back to New York in 1988, I joined the Printing House gym on Hudson St. and started waiting tables at Benny’s Burritos on Greenwich Avenue in the West Village. I was also an active member of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which was based in the community center on Thirteenth Street. Between waiting tables and non-violent political protests, I spent a lot of time running on the treadmill at the Printing House because it made me feel good. Again, I had no aspirations at the time to become an athletic competitor.

Until one day, when a trainer at my gym, Jonathan Cane—who had been watching me run every day at breakneck speed for months—approached me and asked how fast I ran on the treadmill. I said, “I like to set the machine at 10.5 mph and run for an hour.” He said, “That’s really fast!” Because I had been running in a vacuum for so long, I had nothing to compare my running speeds to, and assumed I ran at an average speed. . . Jonathan urged me to enter a race. So in 1989, I ran my first road race, which was the Fifth Avenue Mile on the Upper East Side, in my childhood neighborhood. I ran the mile in 4 minutes and 17 seconds. This performance allowed me to realize that I actually had some potential as an athlete.

"Find Your Adventure": The Odyssey of Ultra-Endurance Athletics

Over the next few years, Jonathan coached and mentored me. I began winning local races in Central Park... However, by the early 1990s, I was getting bored of just running all the time and decided to start training for triathlon. I taught myself to swim, and someone named Ed Tedeschi lent me a racing bike (I couldn’t really afford one at the time). I started competing in triathlons around New York and New England, and had good fortune as a triathlete. In 1994, I won the gold medal in triathlon at the New York City Gay Games. Although it was a world-class event, it was still held in my backyard.

After winning the gold medal at the Gay Games, I decided to take my athletics to a new level. I also realized that I didn’t want to wait tables for a living anymore. Luckily, a friend of mine, who was working as a buyer at Barneys on Seventh Avenue, suggested that I apply for a job at Kiehl’s. He knew that Jami Morse and Klaus von Heidegger, who presided over Kiehl's, had a passion for athletics and both of them understood what it took to become a world champion. I joined Kiehl’s that year as a KCR (Kiehl’s Customer Representative). I worked the sales counter and began training for Ironman triathlons.

In the early 1990s, Kiehl’s was still a very small company. I loved going to work every day. All the images of Aaron Morse flying planes in WWII, the “motorcycle room” filled with dozens of Harley-Davidson’s adorned with the moniker “Fun-In-The-Fast-Lane,” Klaus Heidegger skiing, and the inspiration of climbers summiting Everest with Kiehl’s in their backpacks, got into my DNA. Much like Kiehl’s Since 1851 at the time, I was sort of a “big fish in a small pond.” Some might call me a ‘local hero,’ but I ached to break away from my hometown and go on a quixotic quest for some type of ‘holy grail’ in far away lands. I began romanticizing my journey as a triathlete and set my sights on the Kona Ironman World Championships in Hawaii.

Aaron Morse’s maxim, “Love What You Do, Pour Your Heart Into It, and You Will Be Rewarded” used to be scrawled in bright red lipstick on a floor-to-ceiling mirror, under a chandelier, in the Kiehl’s ‘motorcycle room.’ Aaron’s joie de vivre resonated with me. His wisdom about loving what you do has been my mantra for decades. I loved how quirky Kiehl’s was, and their “free to be. . . you and me” attitude. At Kiehl’s, there seemed to be a paradoxical dedication to the philanthropic Mission of Kiehl’s, “Spirit of Adventure," refined and polite salespeople who were very down-to-earth, and the highest quality standards of natural and science-based ingredients in their products.

I never imagined that I would become a part of the Kiehl’s family when I was growing up in New York City. But, looking back on how my life has unfolded, I credit the epigenetic changes that occurred to my DNA by living and breathing the culture of Kiehl’s for so many years as a KCR with delivering me to where I am in life today. As Kiehl’s U.S. president, Chris Salgardo says, “Success is the pathway to freedom” and “There are no shortcuts.” I couldn’t agree more.

With the encouragement of Jami and Klaus, I began competing in triathlons around the country and doing well on the Ironman circuit. In 1997, I competed in my first Ironman World Championships. In the year 2000, Kiehl’s and I both entered a new phase. Kiehl’s became a more global company and I became more of a world-class athlete.

That year, I took my athletic adventures to the next level. I began competing in Ironman triathlons on different continents around the globe. After qualifying and competing in the Ironman World Championships many times, I decided that I needed more challenges. The regular Ironman had become like a day at the office, it got to be kind of mundane. I craved more exotic adventures.

Take It to the Limit: Triple Ironman, Badwater Ultramarathon, and The Treadathlon

As an athlete, I’ve never been afraid to bite off more than I can chew. In 2001, I got an invitation to compete in the longest non-stop triathlon in the world called a “Triple Ironman.” I remember reading the distances in the elevator up to my apartment: 7.2-mile swim, 336-mile bike, 78.6-mile run all done consecutively with no sleep, only bathroom breaks. I remember thinking, “That’s insane! It can’t be done.” But the thought of swimming, biking, and running three Ironman’s back-to-back gave me a rush of adrenaline and really got my juices going. By the time I opened the door to my apartment, I knew I had to do the Triple. I sent my race application in the next day.

I went on to win the Triple Ironman in a record breaking time of 38 hours and 46 minutes my first year. I also won the race again in 2002 and 2003. That was the “hat-trick” for me, but . . . Predictably, the Triple Ironman started to become ho-hum. The race began to seem like just another loooong day at the office. I needed more challenges. Needless to say, my spirit of adventure was insatiable at this point in my life.

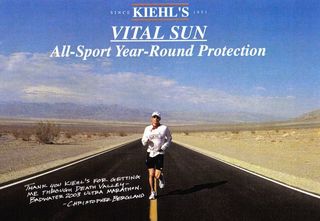

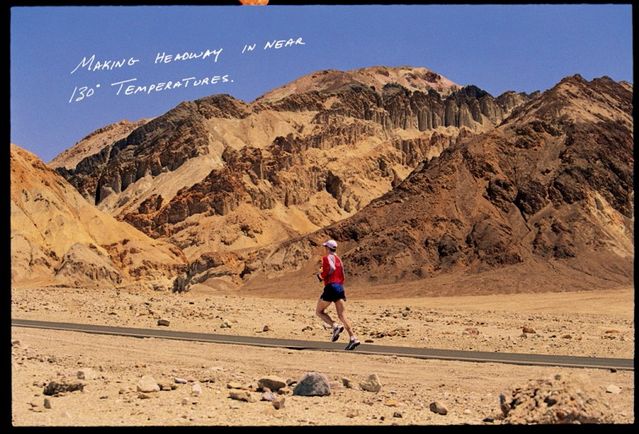

One day in 2003, I heard about the Badwater Ultramarathon—also known as the “World’s Toughest Footrace”—which is a 135-mile run through Death Valley in 130℉ from the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere (282-feet below sea level) to Mt. Whitney, which is the highest peak in the lower 48 states. This race called to my Homer-esque desire to go on epic odysseys to far away unknown worlds.

When I told Kiehl’s about the Badwater Ultramarathon, without missing a beat, our head of PR, Abbie Schiller, said, “That sounds amazing! Let’s take our sunscreens to the hottest, driest, and lowest point on the planet to test their efficacy in the field; just like we tested products in the Himalayas during our Everest ascent in the ‘80s.” Kiehl’s signed up as the title sponsor of the Badwater Ultramarathon and supplied all participants with sunscreen. The products performed flawlessly in these most extreme conditions.

By 2004, I was about to turn forty. I knew that my “glory days” as an ultra-endurance athlete would be coming to an end soon. I wanted to end my career with a bang by bringing adventure racing back to my hometown roots and Kiehl’s Since 1851 in a fundraiser for YouthAIDS. The 24 hour non-stop “Treadathlon” would create perfect synergy of my entire athletic career. It brought together philanthropy, a spirit of adventure, and the Mission of Kiehl’s by showing that if you pour your heart into something you love, you will be rewarded. I asked my original coach and “Jedi Master” Jonathan Cane to monitor and guide me throughout the event. He was there every step of the way during my 153.76 mile 24-hour journey.

On April 29, 2004, Kiehl's closed their East Village Flagship store and set up treadmills in the corner window of the original pharmacy at 13th and 3rd, so that Dean “Ultramarathon Man” Karnazes and I could raise money for YouthAIDS. We were also trying to break a Guinness World Record for the greatest distance traveled on a treadmill in 24 hours. With hundreds of people watching from the sidewalk, and local news crews filming the entire event, Dean and I dueled it out for 24 hours straight in the most intense athletic adventure of my life.

Although Dean and I stayed in a singular location physically, our bodies and minds were pushed to the absolute outer reaches of human possibility. It’s been over 10 years since that event, but I still hold this world record. More than anything, the fact that nobody has officially broken this record for over a decade is a testament to my insatiable drive to explore the outer reaches of human potential and my spirit of adventure, more than my athletic ability.

After the treadmill run, I spent 5 days in the ICU at the Beth Israel Hospital on the verge of kidney failure. My quest for extreme physical adventures had reached a perilous zenith, and there was no place farther for me to go as an athlete. I decided that when I got out of the hospital, I would retire from sports and pour the same amount of passion, quality standard, and dedication to giving back—that had become a part of my DNA through working at Kiehl’s and competing in sports—into becoming a science-based health and wellness writer.

Conclusion: It's Never Too Late to Reinvent Yourself

In 2007, I published my first book The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (St. Martin’s Press). In 2011, I became a blogger for Psychology Today. Currently, I reach millions of readers around the world with science-based, actionable advice. I like to push new horizons as a writer by finding prescriptive ways to apply cutting-edge neuroscience to daily life in an effort to help people optimize their human potential. Researching and writing about neuroscience fulfills my “Spirit of Adventure” these days. My mind, not my body, explores new frontiers now.

Also, as the father of an 8-year-old daughter, I work passionately with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation to improve the well-being and opportunities for children from all walks of life to optimize their health and full human potential . . . . and to make the world a better place.

© 2015 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.