Relationships

Thich Nhat Hanh, Quantum Physics, and Relationships

These ideas from religion and physics can help you work through conflicts.

Posted January 26, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Some scientists and religious figures have converged on the idea that objects are only defined by their relationships.

- This more complex relationship-based perspective offers multiple benefits during difficult conversations and conflicts.

- Shifting your thoughts to the many complex causes at play in conflicts can give you the space to pause before saying something you'll regret.

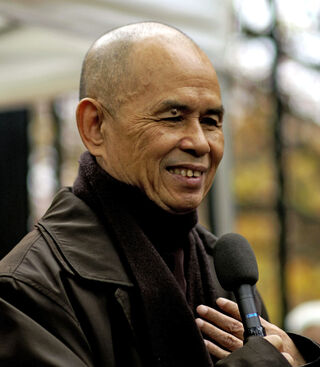

The famous Zen Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh, who died recently, said, “When we touch the conventional truth deeply, we touch the ultimate.” Experiencing anything fully reveals something profound.

This may sound esoteric, but statements like these have moved past the realm of religion. In recent years, some secular philosophers like Graham Priest have used tools including non-well-founded mathematics to advance logical proofs that support the ancient experience Nhat Hanh described.

In his book One, Priest starts from the question: “I am a person….What makes me that particular person?” He uses multiple highly technical and rigorous methods to convincingly show that the only answer to this question can be that he is the particular person he is because of a vast number of relationships that define him. “My being the person I am is constituted by being born in London in 1948, being the child of George and Laura, having the DNA that I do, going to the schools I went to, having the friends I have had…”

What’s more, this is the case not just for persons, but for anything, even abstractions. The number 3 is what it is solely “because of its place in (relation to) the natural number sequence, being the successor of 2, the predecessor of 4, and so on. Any object which related to those things in those ways would ipso facto be the number 3.” So any object exists not because it has an internal essence that can be understood in isolation, but because of how it relates to other objects.

In his 2021 book Helgoland, quantum physicist Carlo Rovelli argues for an interpretation of quantum phenomena that sounds strikingly similar. He writes:

The world that we know, that relates to us, that interests us, what we call ‘reality,’ is the vast web of interacting entities, of which we are a part, that manifest themselves by interacting with each other.... The discovery of quantum theory, I believe, is the discovery that the properties of any entity are nothing other than the way in which that entity influences others. It exists only through its interactions. Quantum theory is the theory of how things influence each other. And this is the best description of nature that we have.

In other words, what quantum physics shows, according to this interpretation, is “the impossibility of separating the properties of an object from the interactions in which these properties manifest themselves and the objects to which they are manifested.” Rovelli gives the example of speed, which is:

relative to another object. If you walk along the deck of a ferry, you have a speed relative to the ferry, a different speed relative to the water in the river, a different one relative to the Earth, another relative to the Sun, another again relative to the galaxy—and so on, endlessly. Speed does not exist without being anchored (implicitly or explicitly) to something else.

Thus speed is never absolute. It is only ever a relation between objects. What Rovelli is saying, though, is that quantum theory actually represents:

the discovery that all the properties (variables) of all objects are relational, just as in the case of speed. Physical variables do not describe things: they describe the way in which things manifest themselves to each other. There is no sense in attributing a value to them if it is not in the course of an interaction.

The idea that Nhat Hanh, Priest, and Rovelli all seem to be converging on is that understanding any object deeply means understanding it as a place in a whole structure, as a node in a network of relationships, and not anything more or other than that. This is a particularly enriching way to think during conflicts.

Have you ever interacted with someone who got on your nerves with their constant references to something that didn’t speak to you: video games, clothes shopping, or their certainty that the answer to every problem is class warfare in which the proletariat will overthrow the bourgeoisie and seize the means of production? When you find that you don’t connect with the perspective someone is taking, try thinking relationally.

Notice that you’re seeing the person in isolation—a particular annoying object that is the cause of your irritation.

But that view is incomplete. To be this person and express this annoying idea means to get that idea from somewhere. Their view comes from a whole network of other people and factors like their upbringing, education, and identity.

What seemed like one fixed point where the problem all originated (the other person) can, with a bit more thought, burst open. It can suddenly explode into a whole moving wave of relationships.

What’s more, for the situation to be annoying, you have a major role to play. You have to perceive what they’re saying in a certain way; making particular associations based on all sorts of factors such as your past reading and how long it’s been since you last had a snack.

The move from thinking about people as the problem in isolation to thinking about entire waves of causes helps difficult relationships to feel more dynamic. There is no fixed annoying person, or fixed you being annoyed at them. There are relationships that are more or less functional for you and for them. You can stop feeling so stuck.

This shift in perspective is empowering because it means that there are many different causes that either of you could work on changing to improve the relationship. This realization can foster new curiosity and creativity. It can also generate an increased sense of mutuality and care for each other.

Pulling back from the drama and seeing a bigger and more complex picture has been shown to help people feel that conflicts they’re involved in are more rewarding. Shifting your thoughts to the many complex causes at play in conflicts can also give you the space to pause before snapping and saying or doing something you’ll regret.

It is little wonder that, with his focus on care for others due to this strong sense of relationship with them, Thich Nhat Hanh was a famous peace advocate.