Media

Can the Left/Right Divide in the US be Bridged?

Polarization, and what causes it, may not be what you thought

Posted October 7, 2019

Recently I was asked to answer questions about my book on an online forum. One question I was asked, that many people seemed particularly interested in, was: “Can the left/right divide in the US be bridged?”

I’ve been collecting the best evidence I can find about such bridge-building for some time. The book offers many practical tips that can be useful to a degree. I'm not claiming they will always work, or offering any guarantees, but I’m sure some of the stories of success and the techniques will surprise you. Here are a few reflections:

1) It’s easy to focus on the extremes. Extreme views and situations get our blood pumping. They’re what we notice and remember. So people on the fringes take up a lot of space relative to the moderate majority, and we start to think more people feel that way than actually do. For example, for decades there’s been widespread scientific consensus that climate change is happening. Shockingly, though, fringe deniers have gotten more mainstream media coverage, even from highly respected outlets, than respected climate scientists!

One study that tried to segment the US population into different political divisions found that, “Segments at the extremes identify more with their ideology than those at the center.” They’re the most entrenched and unyielding. These groups at the margins are also the most internally similar and the most focused on strictly maintaining their group identities—all of which can cause some really damaging groupthink.

2) The divide is often misrepresented. The right/left divide in the US is regularly amplified by the media and in social media debates. In addition to focusing on the fringes, media can fuel polarization through throwing around conjectures about how different segments of society think or why they do what they do. Media pundits regularly state strong opinions based on imaginary caricatures of people rather than on careful evidence.

There are also evidence-based articles that try to over-simplify, boiling complex situations down to “one trait” that supposedly explains for instance support for President Trump, as though there can be just one true reason for anything. Spoiler: even if these articles find one trait that has validity, that trait is hardly representing the whole complex picture of what’s going on. This sort of overly-simplified analysis could encourage us to apply simplistic labels to groups of people, leading us to see them in more one-dimensional ways.

The book has a chapter on peace education that further explains the issues with media coverage of conflicts, but a point to highlight is that if you pick up on differences between people and ask them to talk about those, you can push those people further apart. It’s also possible to pick up on points of commonality, and the truth is, you have a ton in common with people you totally disagree with on many issues.

3) Folks in the US drastically over-estimate how different they are. The divide may be more about identity—seeing oneself as part of a particular group in opposition to the other side—than about actual issues! For instance, Democrats said 52% of Republicans would agree with the statement: “Properly controlled immigration can be good for America.” In fact, 85% of Republicans agreed. The same perception gap exists when asking Republicans about what Democrats believe.

Chapter two of the book looks at othering (the process of seeing someone as an “other” rather than part of your group). It’s full of useful tips that can help when interacting with someone who you experience as being from another political camp (which too often seems to be as strong of a divider in the US as if they were from another planet!)

4) There are experts finding the words and phrases that push our emotional triggers. These words don’t trigger everyone in the same way though, so they contribute to polarizing us between the people who are strongly supportive and strongly opposed. I've posted about this one in more depth. The key point is that we may not be that far apart, but what exact words the issues are conveyed in makes a big difference.

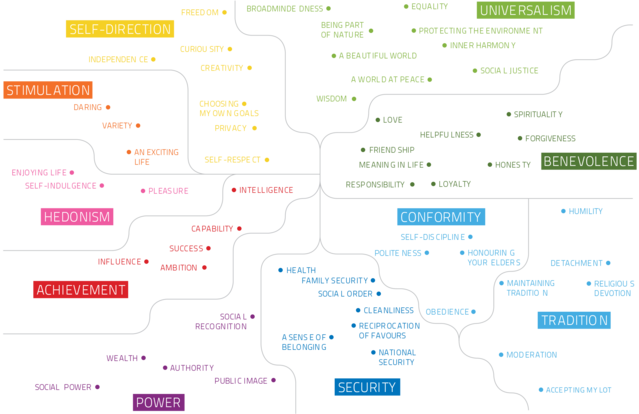

Consider one model of common human values, which has been tested in 82 countries.

This research shows how each of us have different values underlying our positions, and as one value is engaged, that can suppress other contradicting values. So as we think more about security, we tend to think less about universalism, for example. None of these values is “good” or “bad”, they can be useful in some situations more than others, and each of us hold them to different degrees and change our focus on them moment to moment.

We come to our decisions through different routes, but we each feel that the values we’re emphasizing to get there are the right ones — we believe our intentions are good.

Even on supposedly very polarizing issues like gun control and policing, folks change their responses significantly depending on how information is framed. So we need to learn to speak in terms that the other side cares about, understanding what those values are. And we need to be able to translate what they’re saying from their terms into ours to better hear them.

5) We’re heavily influenced by polarizing messages from key people (politicians, news media pundits, celebrities). A major shift could be sparked simply by having a small number of people tone down their rhetoric and look for points of commonality. I’m not saying that’s easy, or even likely, but it’s not impossible. In the book I share a case study of a near civil war in Kenya being averted in part through recruiting influential people to spread peace messages.

I think the same about online information. A handful of companies control the information accessed and shared by billions of people. Right now YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook are designed to maximize how much time we’ll spend on them and how many ads we’ll see. They’re also designed to collect endless data about us, which can be used for psychological profiling and targeted messaging/manipulation. That has some disturbing implications. I believe it is contributing to shifting people’s views—for instance fueling the spread of hateful conspiracy theories. But this also means that just a few decisions by a few companies could drastically improve the situation, if they built their platforms to stop promoting hateful click-bait.

6) Lots of groups are working on countering polarization. Here are just a few:

- https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/bridging_differences

- https://allianceforpeacebuilding.org/resources-for-peacebuilders/domestic-peacebuilding

- https://www.beyondintractability.org/constructive-conflict-initiative-2

- http://ac4.ei.columbia.edu

- https://openmindplatform.org

- https://heterodoxacademy.org

- http://www.civilpolitics.org

- https://www.moreincommon.com

- https://www.nifi.org

- https://echochamber.club

- https://www.citizenuniversity.us

- https://beyondconflictint.org/what-we-do/innovation-lab-for-neuroscience-and-social-conflict

7) The importance of effective listening and communication skills can’t be overstated. The book has a chapter and exercises on that.