Stress

5 Ways Stress Hurts Your Body, and What to Do About It

We store emotional pain in some unlikely spots.

Posted May 7, 2015 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Have you noticed a painful knot in your neck muscles after a stressful week? When you hear a song that reminds you of a difficult breakup, do your hands clench or your shoulders automatically tighten? Have you taken a hip-opener yoga class and wondered why you were filled with strange emotions afterward?

We know that our minds carry our emotional stress, but our bodies do, too. And the physical clues we experience could be telltale signs of emotional memories.

Western-trained doctors and neuroscientists often report that the amygdala or limbic system in the brain stores human emotions and memory. But your body holds onto your past, too. According to the late neuropharmacologist Candace Pert, the "body is your subconscious mind. Our physical body can be changed by the emotions we experience.” Her research reveals the integrated physiology behind emotion-body connection:

“A feeling sparked in our mind-or body-will translate as a peptide being released somewhere. [Organs, tissues, skin, muscle and endocrine glands] all have peptide receptors on them and can access and store emotional information. This means the emotional memory is stored in many places in the body, not just or even primarily, in the brain. You can access emotional memory anywhere in the peptide/receptor network, in any number of ways. I think unexpressed emotions are literally lodged in the body. The real true emotions that need to be expressed are in the body, trying to move up and be expressed and thereby integrated, made whole, and healed.”

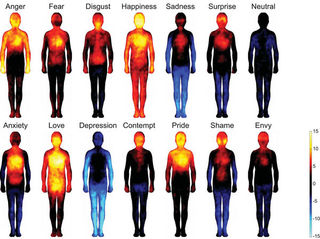

Modern scientific research is still trying to figure out the impact of emotions on the body. One interesting 2013 study tried to portray how we experience emotions in the body. Participants were instructed to color where they actively experienced the emotion in their body. Both European and Asian participants created similar bodily sensation maps for basic and complex emotions, ranging from love to shame.

Anger and pride fire up the head, neck, and shoulders. Love and happiness fill nearly the entire body, especially the heart. Anxiety and fear activate the chest, an area where people with panic attacks often feel tightness. Depression deactivates most of the body, especially the limbs, consistent with the sensation of heavy limbs that many people with depression experience.

The bodily experience of emotion is nearly instantaneous. Research has proven that within the first few seconds of experiencing a negative emotion, people automatically tense the muscles in their jaw and around the eyes and mouth. Neurophysiologists explain that with repeated stress, people over time have shorter and shorter neck and shoulder muscles. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital found that people with depression had chronically tight brow muscles (corrugator muscles) even when they did not think they were frowning. Multiple studies indicate that an increased mental workload results in increased muscle tension in the cervical and shoulder areas, particularly for people working at computers.

Muscle tension can lead to chronic pain, knots, and spasms. One theory is that muscle tension decreases blood flow, leading to lower oxygen delivery, lactic acid buildup, and the accumulation of toxic metabolites. Shortening of the muscle fibers can also activate pain receptors. Lack of movement can further reduce blood flow and oxygenation.

What can we do to prevent storing negative emotions in our tense muscles? Take a moment to see where you might be storing stress in your body. Every body is unique, and our bodies change day to day. Notice where you hold onto different emotions and kickstart the process of releasing negative emotions with the first step—giving your body attention and awareness.

Here are some common areas of tension:

Jaw

Emotions like anger and stress can cause clenching of the jaw and muscles around the mouth.

What to do: Release the jaw by a simple Lion’s breath (or if you’re in an open office, you try yawning or sighing with an open mouth).

Brow

Feeling down or worried can cause you to knit your brow, without even realizing it.

What to do: Release your forehead by raising and lowering your eyebrows 2-3 times. Also, inhale deeply while closing and squinting your eyes tightly, and then exhale while you release the tension and open your eyes.

Neck

If you are constantly looking down at papers or a computer, your neck may be angled in one position for an extended period of time without any movement, causing lower blood flow to neck muscles. Studies have shown that when mental workload increases, the cervical area feels the effects.

What to do: Bring back blood flow to your neck muscles by rolling your head gently from one side to the other, then changing directions. Avoid holding your neck in one position for long periods of time.

Shoulders

The trapezoid muscle of your shoulders holds up your head, which weighs around 10 pounds. If you have a sitting desk or work primarily in front of a computer, you are likely not moving your shoulders regularly, which can create knots and muscle spasms in the trapezoids. Studies show that increased mental workload directly results in physical tension in the arm and shoulders.

What to do: With an inhale, lift your shoulders to your ears. Exhale and draw your shoulders down and back, guiding the shoulder blades towards each other and downwards.

Hips

Most people don’t automatically associate hips with emotions. But many yoga teachers describe hips as storing negative emotions—and hip-opening classes can lead to an unexpected release of emotions.

While there is little scientific data that can shed light on the relationship between negative emotions and hips, one study has shown an interesting connection between the jaw and the hips. After tension of the temporomandibular joint was released, the range of motion of the hip significantly increased.

What to do: Try a hip-opening yoga class or poses.

Thank you to Ossi Raveh & Be Shakti & all the teachers and students at Brooklyn Yoga Project for inspiring this post. Follow me on Twitter @newyorkpsych, @yogahealthtoday and on Facebook.

Copyright © 2015 Marlynn Wei, M.D., PLLC

Medical Disclaimer: The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. This information is not intended to be patient education, does not create any patient-physician relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. Please consult your health care provider to discuss if these exercises are appropriate for your medical condition.

LinkedIn Image Credit: Prostock-studio/Shutterstock

References

Fischer MJ, Riedlinger K, Gutenbrunner C, Bernateck M. Influence of the temporomandibular joint on range of motion of the hip joint in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009 Jun;32(5):364-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.04.003.

Goleman D, Bennett-Goleman T. Relieving Stress: Mind Over Muscle. New York Times. Sept. 28, 1986

Nummenmaa L, Glerean E, Hari R, Hietanen JK. Bodily maps of emotions. PNAS 646–651, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321664111

Pert, C. “Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine.” Available here.

Roman-Liu D, Grabarek I, Bartuzi P, Choromański W. The influence of mental load on muscle tension. Ergonomics. 2013 Jul;56(7):1125-33. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2013.798429. Epub 2013 May 28.

Wang Y, Szeto GP, Chan CC. Effects of physical and mental task demands on cervical and upper limb muscle activity and physiological responses during computer tasks and recovery periods. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011 Nov;111(11):2791-803. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1908-1. Epub 2011 Mar 16.