Anxiety

Does Anxiety Help You Survive in the Modern World?

Lions, tiger, and bears, oh my!

Posted March 21, 2015

Let’s face it, worrying too much can seem pointless. As Shakespeare put it in Julius Caesar:

“A coward dies a thousand times before his death, but the valiant taste of death but once. It seems to me most strange that men should fear, seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come.”

That same reasoning applies to matters a lot less substantial than plots against your life. Is it really worth lying in bed at 3 in the morning worrying about things like: Will I get a $20 service charge for the bill I paid a day late? Will I lose a chance for a promotion at work? Will I have an argument with my neighbor about the tree limb hanging over his property? Will I get a flat tire if I drive to California?

If it’s going to happen, it will happen, and you can deal with it then. But us neurotics suffer a thousand imagined catastrophes for every real mishap.

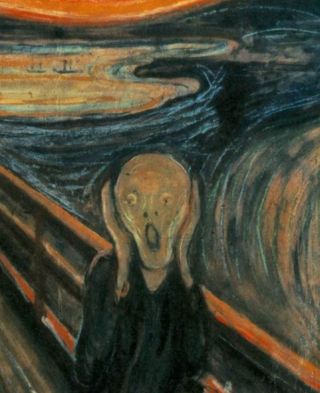

Maybe there’s a silver lining to anxiety, though. Perhaps being a worrywart keeps you from doing something really stupid. In his talk yesterday at the meetings of the International Society for Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, Arizona State University’s Randy Nesse noted that our ancestors had to worry about serious predators such as tigers. If there is even a remote chance of a hungry tiger in the neighborhood, it pays to set our worry mechanisms like a smoke detector – better to have 100 false alarms than to miss one real potentially deadly threat.

What about in the modern world, though. Is anxiety still useful?

In another talk at this inaugural Evolutionary Medicine conference, Plymouth University’s William E. Lee presented some relevant findings from a longitudinal study of 4070 men and women born in the United Kingdom in 1946. As teenagers, these blokes’ levels of anxiety were assessed by their teachers and by their scores on the Maudsley Personality Inventory. The early results suggested a surprising protective function of anxiety, at least for young men. Those who were highly anxious were less likely to die of accidents in early adulthood. They were, however, more likely to die later of non-accidental causes. This seemed to make great sense – worry keeps you away from risky and dangerous activities that might kill you off as a youth, but over the years, it wears out your cardiovascular system.

Although these results made sense, however, a number of later studies by Dr. Lee and others have not replicated them. When he and his colleagues conducted a meta-analysis (statistically combining the results of the various studies on a given topic), it appeared that the initial finding was a fluke. Sadly for us neurotics, it remains true that high levels of anxiety are associated with more disease-related deaths later in life, (Shipley, et al., 2007). But alas, all the worrying does not seem to prevent earlier deaths to any noticeable degree.

One possibility is that the times they are a-changing, such that the modern world is becoming less dangerous than it was even back in 1946. Although the newspapers continue to dwell on the dangers of modern life, it is in fact much less dangerous to live today than it was in the good old days (see Is the world becoming a nicer place to live?).

Another possibility is that anxiety is still adaptive, but only in very small doses -- the level of worry that keeps most normal people from rock climbing in Yosemite without a rope or jumping into the tiger cage at the zoo. Higher than normal levels of anxiety may not be necessary, and may indeed be harmful, especially in the modern world.

Why do some individuals have anxiety levels that interfere with, and eventually shorten, their everyday lives? Northwestern University's Jon Maner and I discussed several possibilities in a paper called “When adaptations go awry: Functional and dysfunctional aspects of social anxiety.” For one, there is sometimes a mismatch between our current environments and the environments in which our psychological mechanisms evolved (most of us no longer need to worry about lions, tigers, or bears). For another, every decision involves trade-offs: anxiety can keep you out of troubles, but worry-driven avoidance can also keep you from enjoying many of life’s opportunities. Where you set your personal smoke detector will depend in part on your recent and chronic experiences. A combination of genetic predispositions and past sensitizing experiences will lead to a range of individual differences in anxiety, and some of us will simply be less lucky than others.

But that’s all in the past. Maybe you should try not to worry about it too much.

----------------

Douglas Kenrick is author of The Rational Animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think, and Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature.

-----------

Related Posts

7 good things about feeling bad: The bright side of sadness.

Is the world becoming a nicer place to live?

References

Lee, W. E., Wadsworth, M. E. J., & Hotopf, M. (2006). The protective role of trait anxiety: a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological medicine, 36(03), 345-351.

Maner, J. K., & Kenrick, D. T. (2010). When adaptations go awry: functional and dysfunctional aspects of social anxiety. Social issues and policy review, 4(1), 111-142.

Nesse, R. M. (2005). Natural selection and the regulation of defenses: A signal detection analysis of the smoke detector principle. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(1), 88-105.

Shipley, B. A., Weiss, A., Der, G., Taylor, M. D., & Deary, I. J. (2007). Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: a 21-year prospective cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(9), 923-931.