Motivation

Choose the Path of Least Friction to Change Your Behavior

Overcome major obstacles with these proven self-regulation strategies.

Posted January 19, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

A new year is upon us. A time for self-reflection and new goals. For many, setting New Year's resolutions is a highly motivating task. After all, the promise of a new beginning creates excitement. You resolve to eat better, exercise more, and be more productive. Unfortunately, more likely than not, that excitement is short-lived. You may soon find yourself avoiding the gym, ordering pizza, and binge-watching episodes of your favorite Netflix series. Despite your best intentions, you are back to square one.

Sound familiar? If so, know that you're not alone. According to research from the University of Scranton, a staggering 92 percent of people who set New Year's goals fail to achieve them. Why? Because behavior change is hard. Despite our best intentions, desired actions can become quickly hampered by various obstacles that interfere with our motivation.

Experts agree that the key to lasting behavior change is to develop new habits. Habits are learned behaviors that we routinely perform, without much thought. Once an action has become part of your routine, it requires minimal effort and happens automatically.

The Science Behind Habit Formation

According to Stanford professor BJ Fogg, there is an exact science to making lasting behavior changes. In his book, Tiny Habits, Fogg describes three key ingredients that trigger behavior change: motivation, ability, and a prompt.

Motivation is our general desire or willingness to do something. You may feel motivated after watching an inspiring TED Talk, listening to your favorite celebrity speak, or hearing about your coworker's fantastic weight loss journey.

Ability refers to the level of difficulty in engaging in the desired behavior. According to Fogg, when motivation and ability are both present, a prompt or cue will elicit the desired action.

For example, many retail stores now ask customers if they would like to donate to a charity (the prompt) during the checkout process. Retailers make this process easy (ability) by displaying several dollar amounts right on the payment screen. With one click, the donation is added to your purchase. If the charity is one that you care about (motivation), then you're more likely to donate even if you hadn't planned on donating that day.

Fogg's behavior model is simple and straightforward. When a behavior is easy, we need less motivation to do it. Conversely, if the desired behavior is challenging, we will need more motivation to do it. Fogg contends that most people rely too heavily on trying to stay motivated to change a behavior. The problem with this strategy is that motivation can fluctuate from one minute to the next, making it an unreliable source (by itself) for lasting behavior change. Instead, Fogg suggests keeping it simple. Make the desired new behavior easy, and you will be more likely to repeat it. In essence, remove any potential friction.

How Friction Disrupts Behavior Change

We can all agree that sometimes even the smallest behavior change can seem daunting. New desired behaviors have to work against other deeply rooted, automatic habits. When we introduce a new practice into our routine, we will inevitably experience roadblocks. In the book, Friction, author Roger Dooley discusses how friction—"the mortal enemy of motivation"—interferes with behavior change.

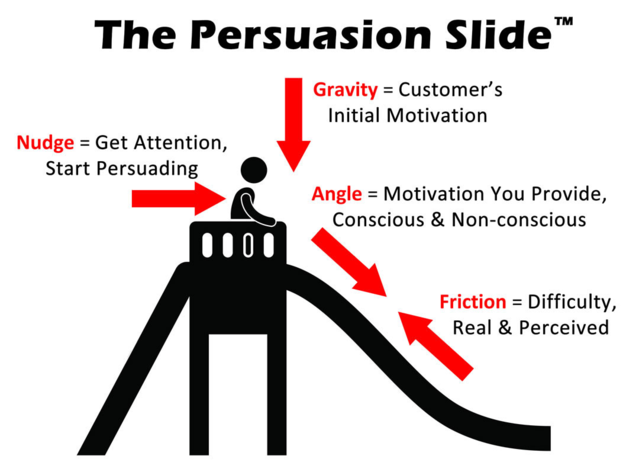

To further illustrate this, Dooley created The Persuasion SlideTM to describe his framework for the behavior change process.

Imagine that you're sitting at the top of a playground slide. To start your journey down the slide, you first need a little nudge (i.e., a prompt or cue). Once you start moving, gravity (i.e., motivation) takes over, propelling you down the slide.

Unless, of course, you run into some friction.

Friction works against gravity, forcing you to slow down—or worse, stop altogether. We can all envision those times when we lost our initial momentum and became "stuck on the slide." When we encounter friction, we must put in extra effort to complete our journey down the slide.

Friction comes in many different shapes and guises (e.g., distraction, state of mind, environment, negative self-belief, etc.). Typically, when we set goals, we feel upbeat, positive, and motivated to make a change. When we're in that mindset, we fail to recognize potential barriers that will interfere with our goals. We believe that we can resist temptation. However, in reality, moods fluctuate, motivation wanes, and old habits take over—making it challenging to stay on track.

Why Intentions Without a Plan Are Useless

Good intentions will only get you so far. After all, ancient folklore tells us that "the road to hell is paved with good intentions." Having positive intentions is not enough to generate change; we must take action to fully achieve it.

When we set a new goal (i.e., goal intention), we tend to focus on the desired outcome—"I will lose x amount of weight this year" or "I will have a better work-life balance." However, having a firm goal intention does not guarantee goal achievement. Successful behavior change involves actively committing to goals, ongoing persistence in achieving them, and planning how to overcome potential obstacles (i.e., friction) to attaining those goals. Unfortunately, people often fail to predict and plan for self-regulatory problems that they will inevitably experience along the way.

For example, let's say your goal is to eat better. As part of that goal, you decide that you will give up eating fast food. However, while setting this goal, you fail to plan for what might happen when you're starving and driving past a row of fast-food restaurants after work.

Human behavior is predictable. We gravitate toward the path of least resistance.

So, if you find yourself famished after work, are you more likely to go home and spend time preparing a healthy meal or make a pit stop and the nearest fast food restaurant? The key to lasting behavior change is to remove the need to make a decision when faced with temptation (or friction).

Avoid Friction With These Self-Regulation Strategies

Self-regulation plays an essential role in human behavior. It involves the ability to control one's own thoughts, emotions, and actions in the pursuit of long-term goals. Psychologists have proposed the use of self-regulation strategies to proactively design behavior change. Two strategies in particular—mental contrasting and implementation intentions—have proven to be effective in promoting lasting behavior change.

Mental Contrasting

Mental Contrasting is a powerful, visualization technique developed by psychologist, Gabriele Oettingen, that helps people fully commit to their goals by understanding how to overcome obstacles. Mental contrasting involves three steps. First, you name a desired and feasible future wish (e.g., having a better work-life balance). Second, you identify and vividly imagine the best outcome of fulfilling that wish (e.g., having less guilt, feeling like a better parent, accomplishing more tasks each day). Third, you identify and vividly imagine a critical obstacle that could interfere with the desired outcome (e.g., feeling pressure to make partner at my firm). This technique helps people understand how to overcome their obstacle (e.g., delegating tasks when feeling overwhelmed) and energizes people to commit to and actively strive for their desired future.

Implementation Intentions

Implementation intentions are another self-regulation strategy that helps people plan how they will deal with certain challenging situations. Introduced by NYU professor, Peter Gollwitzer, the approach involves creating an "if-then" plan that specifies the when, where, and how portions of goal-directed behavior. The idea is, "if (obstacle) happens, then I will (behavior or thought to overcome obstacle)." For example, if your goal is to study more, your "if-then" plan might look something like this, "If my roommates ask me to go to the bar, then I will tell them I will go another night."

Mental Contrasting and Implementation Intentions (MCII)

Researchers have found that a combination of mental contrasting and implementation intentions (MCII) is even more effective in changing behavior than each of the two strategies alone. In one recent study, researchers tested the effectiveness of using MCII to reduce bedtime procrastination. They conducted two separate studies using a group of undergraduate college students. In the first study, they used a motivation-relevant control exercise. In study two, they used a sleep hygiene control group. The researchers found that for both studies, subjects in the MCII group increased their commitment to reducing bedtime procrastination—as measured by the average number of minutes of bedtime procrastination per night—than those in each of the control groups. Other studies have demonstrated MCII's effectiveness in promoting healthier habits, prosocial behavior, and academic performance.

If you would like to apply these strategies to your own goal pursuits, just remember the acronym WOOP—Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan. For more information on how to use these self-regulation techniques, visit woopmylife.org.

References

Dooley, R. (2019). Friction: The untapped force that can be your most powerful advantage. New York: McGraw Hill.

Fogg, B.J. (2020). Tiny habits: The small changes that change everything. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. The American psychologist, 54(7), 493-503.

Oettingen, G. (2000). Expectancy effects on behavior depend on self-regulatory thought. Social Cognition, 18, 101–129.

Valshtein, T. J., Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2019). Using mental contrasting with implementation intentions to reduce bedtime procrastination: Two randomized trials. Psychology & Health, 1-27.