When recalling our past for our family or for a wider audience, how should we select and tell our personal memories? What obligations do we have to our memories, to our audience, and to the people we are remembering? The answers to these questions lead to a morality of memoir, a set of principles for guiding the way we tell our life stories.

1) The first principle in writing our memories is to begin by striving for honesty and comprehensiveness.

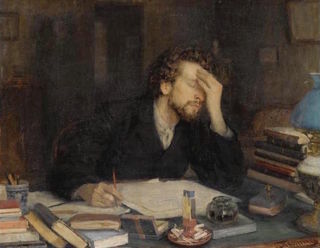

Make concentrated, effortful recall, with no goal other than to remember. If we are remembering personal events to make a point or to bolster a belief about ourselves, then the information from memory may be biased to support that point or belief. It is best to retrieve a memory, study the images that come to mind, and write everything we see in our mind’s eye. We can then let that memory lead to other memories and describe those linked memories in the same way.

It also helps to focus on the sensory qualities of our original experience, feeling what we felt when we first experienced the remembered events. The sights, the sounds, the smells, the emotions, the bodily sensations. In general, freely recalling vivid personal memories by reading from memory images is an effective method for recapturing our original experiences.

2) Become familiar with the literature on memory research. Find out what we are good at remembering and what kinds of predictable mistakes we make.

One common mistake of memory is blending two similar events. We may, for example, insert a familiar person in an event, even when that person was not there. We accurately remember the event and we accurately remember the person, but we blend the two and create a composite image.

We remember the gist of events very accurately, but because our memory is gistified quickly, we may lose specifics. This is especially true with conversation. Exact phrasing is often transformed into general meaning which is then transformed into specific words that may differ from the original words, while still representing the original meaning.

We can also make mistakes if we are answering questions about our past that we aren’t sure of. This cued recall is less accurate than free recall because we answer questions by drawing on general knowledge, which may not apply to the specific event in question. When in doubt, we often draw on the most likely information, when, in fact, the answer may be different.

The 1999 article entitled "The Seven Sins of Memory" by Daniel Schacter is a very helpful introduction – as is David Pillemer’s Momentous Events, Vivid Memories.

3) To the extent possible, compare written memories with existing documentation.

Important events in our lives are often documented. Medical records, birth certificates, photographs, home videos, legal documents, playlists from concerts, Facebook timelines, and personal journals can verify memories and specify details.

4) If possible, revisit the places of memory.

Visiting the actual places of memory can provide helpful details and show us what we have forgotten. Place is a universal petite madeleine, retrieving memories not thought about for many years.

5) Be aware that memory is selective.

In the short story "Funes the Memorious," Jorge Borges writes about a young man, Funes, who is thrown from a horse and permanently paralyzed. Funes then spends his days in a darkened room working diligently to develop his memory, which eventually becomes so prodigious that he remembers every detail in his life. The difficulty of this position is illustrated by the fact that when Funes recalls the events of the previous day, it takes a full twenty-four hours to do so. We do not remember that way. We forget a lot. In fact, forgetting trivial details is a necessary part of remembering what’s important.

6) Memory is selective, but memoir is even more selective.

Honesty comes in layers. After we recall as comprehensively as we can, we need to select from these memory descriptions for our memoir, which may be the most difficult of all the judgments in writing memories. What should we leave out, while trying to remain fiercely honest?

The specific decisions are up to the individual memoirist, but it’s important to know that such decisions are necessary in writing memoir.

One main reason for omitting information voluntarily is to avoid exposing other people's secrets. Another reason for being selective is to create a balance between providing too much detail to the point of tedium and withholding too much to the point of incompleteness or confusion.

7) After writing memories, carefully review the written descriptions. Consider the likely mistakes of memory, while also maintaining confidence in memory.

We blend different events. We draw on general knowledge or second hand information (like photographs) in constructing our personal memories. But unless we’ve been hypnotized or relentlessly interrogated, we do not fabricate memories. It is reasonable to assume that our memory corresponds to our original experience – especially with distinctive events that we’ve personally experienced after the age of four.

Final Thoughts

Each of us has a life story to tell, with memory providing the first draft. We have not evolved to misremember the world, and we can depend on our memory for writing this first draft. We can strive to remember our original experiences comprehensively and honestly, while also being aware of the predictable mistakes of memory and the potential for our memories to hurt others. It is our story to tell, but it is also important to consider guidelines that make up a morality of memoir.