Stress

Have You Lost Your Mind?

Stress and trauma damage the brain: Fact or theory?

Posted July 30, 2017

I was quoted in an Associated Press (AP) article that was published July 12, 2017. The article, How Severe, Ongoing Stress Can Affect a Child’s Brain, presents the popular theory that psychological stress harms children’s brains. The author of the story, and so-called experts quoted in the story, referred to this type of psychological stress as “toxic stress.”

Psychological stress is toxic, huh? Is it toxic just a little bit, like the itchy bump you get from a mosquito bite? Or is it toxic a moderate amount, like a whole body rash from poison ivy? Or is the toxic level really bad, like a skin-peeling infection that will kill you?

The online AP article included a super-scary companion video in which eminent Harvard neuroscientist Charles Nelson clarified the toxic level for us, “So, we know that high levels of toxic stress that occur early in life, and then continue, can lead to an increase risk of diabetes and heart disease as well.”

Oh, I see. It is toxic like it will kill you. Toxic stress allegedly increases the risk of the #1 and #8 deadliest diseases in the whole world. That is extraordinary. If we believe these claims, it seems that millions of children exposed to stress every year are, literally, losing their minds.

The super-scary video also included an interview with a pediatrician in Caro, Michigan, Tina Hahn, MD who said, “Dealing with and preventing toxic stress is the most important thing that we can do in medicine.” Really? Not immunizations? Not treatment of respiratory infections?

The stress-damages-the-brain theory is not a new theory. Experts have been trotting out this theory for over 30 years, nearly as long as research on PTSD has been conducted. I am not quite ready to believe this extraordinary claim, and I was quoted as the lone skeptic in the story.

There are many things wrong with this article, in my opinion. One problem is that this theory is not a fact. The title of the article was not If stress can affect a child’s brain, it was How, as if it were an established scientific fact. The article did more than present this notion as a theory. The article crossed the line and presented it as an accepted fact, which while often viewed as just a speed bump to roll over for many folks in the media, crossing the line from theory to fact is kind of a big deal for scientists. Or at least, it is supposed to be.

The author, AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner, has written several articles on the notion that stress damages the brain. When she contacted me by email to ask if I would be interviewed, her email said she was preparing a story “to explain and raise awareness about toxic stress and PTSD in very young children.” Not if stress is toxic, mind you, but to promote the fact that it is toxic.

I replied that I did not believe the theory and probably wasn’t who she was looking to talk with. She wanted to talk anyway. On the phone, Tanner expressed some level of dismay that I did not agree with all of the other scientists. I wondered if she thought I had lost my mind.

I told her that there were several newer studies that were designed better than the old studies, and the newer studies directly contradicted the theory that stress damages the brain. I gave her the details of one of those studies, none of which ended up in her story.

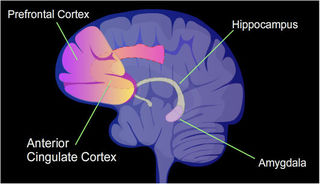

Here’s an example of one of the newer studies with a better research design. Psychologist Katie McLaughlin and a group of researchers in Boston possessed, by chance, fMRI scans on 15 adolescents prior to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing (McLaughlin et al., 2014). In this study, adolescents viewed negative emotional stimuli while their brains were scanned, and the researchers measured the degree of activation of the amygdala and hippocampus.

Then by chance, the Boston Marathon bombing attack occurred. The adolescents lived in the area while the shelter-in-place order existed and the police hunted for the terrorists. The PTSD symptoms of the adolescents were measured more than one month after the attack. The researchers found that the individuals who developed more PTSD symptoms after the bombing had different amygdalae, and also probably different hippocampi, before the bombing occurred. Those who developed more PTSD symptoms were different prior to the attack compared to those who developed fewer PTSD symptoms, and the differences in their amygdala and hippocampi could not be attributed to the stress.

Why should we believe the Boston Marathon study and not the toxic stress theory? Why was the design of the Boston Marathon study more powerful than older studies? In nearly all of the older studies, researchers examined individuals at only one point in time and that one point in time was always after the traumatic events had occurred. In contrast, in the Boston Marathon study, researchers examined individuals at two points in time, and the first of those was before the traumatic event.

In the older studies, because the individuals’ brains were examined only after the traumatic events, one can never know if their brains changed because of the traumatic events.

When brains are examined after, as opposed to before, traumatic events, such studies have absolutely no power to make causal conclusions about what caused what. Any good researcher knows that, but in nearly all of the older studies in humans that researchers and journalists have cited to support the toxic stress theory, the brains were examined only after traumatic events. And yet many researchers and journalists nevertheless state as fact that stress damages the brain. They seem all too willing to promote this theory as fact. It makes me wonder: Have they lost their minds?

References

McLaughlin, K.A. et al., (2014). Amygdala response to negative stimuli predicts PTSD symptom onset following a terrorist attack. Depression and Anxiety 31(10), 834-842.

Tanner, L. (2017, July 12). How severe, ongoing stress can affect a child’s brain. The Associated Press. Retrieved from apnews.com.