Eating Disorders

Why Interpersonal Difficulties Need to Be Addressed Alongside Eating Disorders

Social problems for a young person can interfere with treatment.

Posted May 1, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Interpersonal difficulties are common among people with eating disorders, but tend to improve with the remission of the eating disorder.

- Some people have marked interpersonal difficulties that maintain the eating disorder and create on obstacle to change.

- When the interpersonal difficulties are marked they should be directly addressed during the treatment of the eating disorder.

Interpersonal difficulties are common in people with an eating disorder but generally don’t interfere in the treatment’s progress. In fact, the difficulties get better on their own if the eating disorder is successfully treated. However, some people have such severe interpersonal problems that reinforce their eating disorder and/or interfere with its treatment.

Here are some examples of marked interpersonal difficulties that tend to maintain the eating disorder and/or interfere with the implementation of the treatment:

Social isolation and interpersonal functioning deficit

The most frequent interpersonal problem in young people with eating disorders is the lack of fulfilling relationships. People with this problem lack social skills, struggle to meet and connect to similar people, or react strangely to relationships. In these situations, the pursuit of thinness can become a dysfunctional way of trying to please others and develop more intimate and satisfying relationships.

Interpersonal conflicts

These typically occur when a person and at least one significant other do not share the same expectations about the roles they should have in the relationship. Arguments of this nature may be present with any important figure in the life of a person with an eating disorder, including parents, siblings, partners, and friends, and can trigger and maintain eating disorders in some individuals.

For example, if a susceptible 17-year-old girl is constantly treated like a child by her parent(s), she may decide to assert her independence by controlling what she eats. Unfortunately, the most likely parental reaction to this kind of behavior is to treat the 17-year-old even more like a child. Dysfunctional behaviors can be also used as a coping strategy, and it is not unheard of for teenagers to use binge eating, for example, as a response to the negative emotions triggered by a conflictual relationship.

Role transition

It is not easy to be a teenager. This age group has to deal with important changes in hormone levels, body shape, environment (for example, starting a new school), and roles ("growing up"), which may be confusing and distressing. Puberty begins in early adolescence, and the resulting development of "secondary sexual characteristics" (i.e., pubic hair, breasts and changing hip shape in females, and increased muscle mass in males) is a significant change. This can trigger anxiety and vulnerability in some teens and bring a sense of loss regarding their known and "safe" childlike bodies. Adolescence is also a period in which some experiment sexually for the first time. Indeed, their changing bodies attract greater attention from the other sex, which some may find difficult to handle.

All of these changes can cause a sense of loss of control when they feel a need to develop their autonomy. This may be why some teens decide to curb their eating—both as a means of feeling in control and in an attempt to revert to their "safe" prepubescent body shape. Dysfunctional strategies for coping with the physical, psychological, and social changes brought on by puberty are common in young people with eating disorders.

Mechanisms of maintenance of the eating disorder

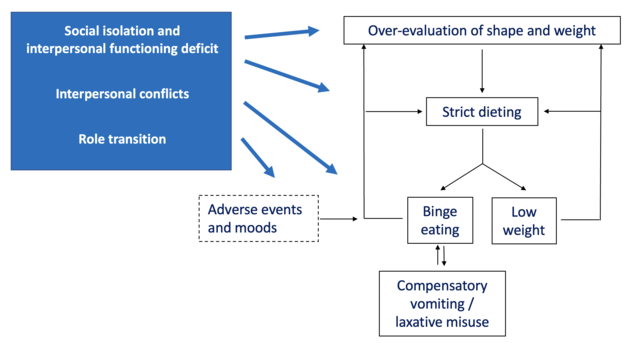

Marked interpersonal difficulties tend to maintain the eating disorder and obstruct treatment progress through several mechanisms (Figure):

- They intensify the overvaluation of shape, weight, eating, and control, as they hinder the development of other self-evaluation domains.

- They can drive an individual deeper into their eating disorder as a way to escape, avoid and distract from interpersonal difficulties.

- They may worsen self-esteem and, consequently, encourage the use of shape, weight, and eating control to improve self-evaluation.

- They may precipitate episodes of binge eating, and there is evidence that patients with bulimia nervosa tend to be particularly sensitive to social interactions.

Interference with treatment

There is evidence that poor interpersonal functioning predicts a poor response to treatment. In fact, when interpersonal difficulties are marked they inevitably interfere with treatment. Two examples are:

- Interpersonal turbulence. When life difficulties hijack treatment sessions or interfere with the patients’ compliance with homework.

- Interpersonal vacuum. When an absence of relationships prevents patients from exploiting some aspects of treatment (such as developing new self-evaluation domains).

Addressing interpersonal difficulties

Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E), a recommended, evidence-based treatment for eating disorders in adults and adolescents, directly addresses interpersonal difficulties when:

- They are contributing significantly to maintaining the patients' eating disorder

- They are interfering with the implementation of treatment

- It has been decided that core low self-esteem should be addressed by tackling interpersonal difficulties

This decision is usually taken after four weeks in people who are not underweight or during the process of weight regain in those who are underweight. The analysis of the interpersonal history of the person can help understand whether interpersonal difficulties need to be addressed by the treatment. Moreover, this procedure helps to identify the most impactful interpersonal problems and whether there are other associated problematic interpersonal issues. If the conclusion is reached that interpersonal difficulties are a problem to address, the treatment should address both interpersonal problems simultaneously as addressing the eating disorder.

CBT-E addresses the interpersonal difficulties in a specific module with two interrelated goals: (1) to resolve the identified interpersonal problem or problems, and (2) to improve patients' interpersonal functioning generally. The two goals may be achieved using two main strategies.

The first is combining the CBT-E with interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), an evidence-based psychological treatment specifically designed to improve current interpersonal functioning. IPT was created for the management of clinical depression but it has since been shown to be effective in treating bulimia nervosa. Indeed, it is the leading empirically-supported treatment for bulimia nervosa after CBT.

The second is using cognitive-behavioral strategies and procedures to address the main cognitive processes maintaining the interpersonal difficulties. These include, among the others, problem-solving, assertive communication, addressing interpersonal avoidance, cognitive restructuration of dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs, and developing new interests and relationships. The advantage of using cognitive-behavioral strategies is maintaining a similar approach to that used to address the eating disorder without confusing patients or reducing the risks of diluting their individual effects. Furthermore, only a few clinicians are trained both in CBT-E and IPT, and those trained in CBT-E are usually more confident in using cognitive-behavioral strategies and procedures than in IPT.

The improvement of interpersonal difficulties achieves beneficial effects through several potential mechanisms. For example, helping to address role transition may be of great help for people who, due to the effects of the eating disorder, have missed out on some of the common interpersonal challenges of adolescence. In others, the increased importance of the interpersonal aspect of life in their self-evaluation can indirectly reduce the importance they attribute to the control of eating, shape, and weight. Finally, in some people, the sense of influencing their interpersonal life may reduce their need to control eating, shape, and weight.

To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Dalle Grave R, el Khazen C. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders in young people: a parents' guide. London: Routledge; 2022.

Dalle Grave R, Calugi S. Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2020.

Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.