Personality

Getting Outside of Your Own Head

Why do we think others are like us?

Posted December 18, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- We sometimes project our ideas of who we are onto others.

- We are likely to project when we know someone well and when traits are connected to personal values.

- We are not actually that similar to others in terms of personality traits.

It’s the holiday season, and I’ve been buying gifts for people. Just this week I bought my friend a shirt I wanted and my nephew a hat I wanted. I bought my wife a candle that I thought smelled nice. These purchases all rest on the assumption that things I like, others close to me might also like.

The general phenomenon of a correspondence between one’s attitudes and preferences and those of the general public has been termed by social psychologists a false consensus effect (Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). Its cousin in personality psychology is a similar phenomenon in which we observe a positive correlation between how one sees themselves and how they see other individuals in terms of general thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. For example, if I am more introverted, I may have a general assumption that others are also introverted.

Personality psychologists have referred to this tendency as assumed similarity, perceived similarity, social projection, the self-based heuristic, and probably a few other terms. The terminology matters here, and I will return to that point in a moment. But the more appropriate initial question is whether we tend to do this as a rule. That answer, like many answers in psychological science, is a bit complicated, but the short version is probably yes—we do tend to assume similarity, at least to some degree. Some greater complications arise when we look a bit deeper and ask under what conditions we assume similarity and/or why we have this tendency. And this will take us back to how to name the phenomenon.

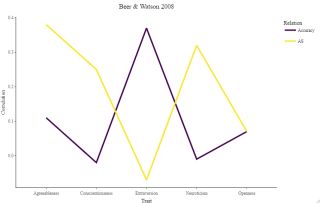

Early in my research career, I was very interested in assumed similarity, and one of my first projects as a graduate student resulted in a paper (Beer & Watson, 2008) in which we demonstrated that assumed similarity tended to occur more often when a) we were less familiar with the person we were thinking about and b) when it was pertaining to a less “visible” trait (i.e., traits about which we more accurate in judging others showed lower assumed similarity, and vice versa).

This general pattern of results mirrored an earlier study showing similar findings, and these findings jointly supported a growing sense that perhaps assuming similarity was best termed a “self-based heuristic” (Ready et al., 2000)—a simple judgment strategy to fill in the gaps when we lack good information about a person and their characteristics. This implies a non-conscious, fairly automatic fallback option, as opposed to a conscious choice to consider oneself and the other jointly and to actively assume similarity, for example. Mystery solved; onto the next big important question for me.

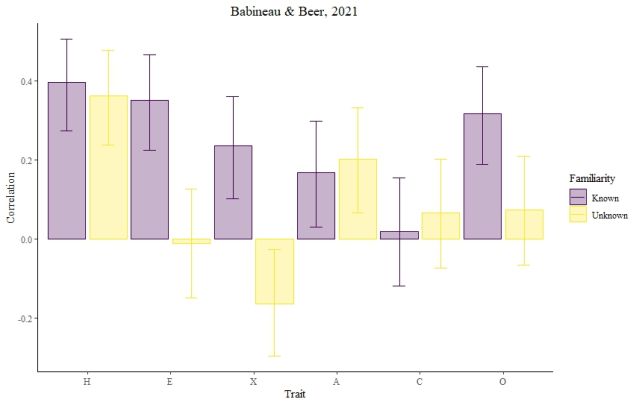

Except it wasn’t. While I was otherwise occupied, better scientists were hard at work unraveling this particular myth. The culmination of these efforts, in my opinion, was somewhat recently published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Thielmann, Hilbig, & Zettler, 2020). Here, Thielmann and colleagues looked back over the corpus of research on assumed similarity for personality traits, conducted several studies of their own, and came to some different conclusions. Namely, they found that in reality, assumed similarity is slightly greater for those whom we know better, and that visibility of the trait is probably less important than the trait’s connection to one’s personal values. That is, we tend to assume that close others are more similar to us, and we tend to assume similarity specifically for traits like honesty and openness to experience (two traits that typically correlate with value orientations). Thus, I was wrong for neither the first nor the last time. In fact, I wanted to see my wrongness in all its glory, so with the help of some of my undergraduate research assistants (thanks, Becca Babineau and Chris Camillo), we successfully replicated Thielmann et al.'s (2020) general findings:

At this point, you are rightfully asking, “But what about the gifts—you’ve talked about when we assume similarity but should we assume similarity? When is false consensus indeed false?” Well, in terms of personality, quite a bit—we are actually not all that similar to people close to us (Watson et al., 2004). So though it seems perfectly logical to assume that close others share our characteristics, it is probably often inaccurate, as I’ve (occasionally painfully) learned.

“OK, so don’t buy gifts I like?” The better news here is that we actually do tend to cluster with people who share attitudes and values with us (see the same reference above). So there’s a reasonable chance that my friend will like his shirt--even though I’m silly and he’s serious—as personality and likes and dislikes aren't the same thing. In the meantime, the precise reason why we tend to assume similarity more for some things (and people) than for others isn’t fully settled. Are we motivated to feel closer to others? Do we want our worldview upheld, even if only in our own minds? Thielmann et al. have provided some good starting points for others to carry forth. I can only assume many will have great interest in doing so.

References

Babineau, R., & Beer, A. (2021). Assumed similarity and valued personality characteristics. USC Upstate Student Research Journal, 14, 1-8.

Beer, A., & Watson, D. (2008). Personality Judgment at Zero Acquaintance: Agreement, Assumed Similarity, and Implicit Simplicity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(3), 250–260.

Ready, R. E., Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Westerhouse, K. (2000). Self- and Peer-Reported Personality: Agreement, Trait Ratability, and the “Self-Based Heuristic.” Journal of Research in Personality, 34(2), 208–224.

Ross, L., Greene, D., and House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: an egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 13, 279–301.

Thielmann, I., Hilbig, B. E., & Zettler, I. (2020). Seeing Me, Seeing You: Testing Competing Accounts of Assumed Similarity in Personality Judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(1), 172–198.

Watson, D., Klohnen, E. C., Casillas, A., Nus Simms, E., Haig, J., & Berry, D. S. (2004). Match Makers and Deal Breakers: Analyses of Assortative Mating in Newlywed Couples. Journal of Personality, 72(5), 1029–1068.