Identity

If These Walls Could Talk

Personal Perspective: What you say about your stuff, and what it says about you.

Posted August 24, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The physical spaces we inhabit contain clues to our personality.

- Objects in our lives often have personal meaning that is not immediately obvious to others.

- Talking about our things is talking about ourselves.

This fall will be the first time I return to my office full-time since…well, you know. As I’ve been settling in, I’ve been able to look at my office with fresh eyes, and it’s brought to mind some research, both old and new.

Last spring, my students chose to read and discuss the article “The ‘Stuff’ of Narrative Identity: Touring Big and Small Stories in Emerging Adults’ Dorm Rooms” (Breen, Scott, & McLean, 2021), in which the authors merge two interesting and theretofore largely separate streams of research. Essentially, the authors consider whether telling stories about our stuff can give insight into what someone is like. This general line of inquiry is at least a couple of decades old, the seminal piece being Gosling et al. (2002) or, alternatively, Sam Gosling’s book, Snoop (2008). In these works, Gosling et al. lay out the theoretical rationale for connecting personality with our physical environments.

How do our personalities appear in our physical spaces?

Gosling et al. (2002) suggest two primary pathways to personality’s connections to our physical spaces: via identity claims or via behavioral residue. Identity claims involve largely conscious choices of surrounding oneself with objects that signify something about the person. My portrait of Tom Waits and my Radiohead poster are things that remind me of who I am and what I like, tastes that individuate me to some degree. The former is hung on the wall (well, it’s on the floor temporarily), and the latter is on the back of my door (and thus only seen by me when the door is shut).

These distinctions may matter, as Gosling et al. suggest that identity claims can be self-directed (meant for me) or other-directed (meant for others). That is, sometimes I want people to know something about me (like when I put a bumper sticker on my car), and sometimes I want to remind myself of something. Obviously, many objects serve in both capacities.

Beyond the claims we make about ourselves, there is also evidence of our actions in our spaces or behavioral residue. Underneath my Danish Modern chair are my running shoes, which represent exterior behavioral residue or evidence of something I do (or did) outside the space itself. The disassembled remote light switch on my desk is interior behavioral residue, indicative of something I’ve done or am doing inside the space (fixing the switch).

People’s personal spaces are full of opportunities to examine behavioral residue and identity claims, which have been quantitatively assessed and connected to measures of people’s personalities, yielding fun findings, such as conscientious people have homogeneous book collections or neurotic individuals have more decorations in their offices.

So why stories about stuff?

The connections above are fascinating, but anyone who has a personal space knows that a stranger’s appraisal is probably missing context. When I referenced my Danish Modern chair, it may have given the impression that I carefully choose my office furniture and comb through various antique dealers looking for just the right piece, and not that a colleague had dumped said chair in the hallway, and I snatched it up despite its ill fit with my existing office décor. These convey very different messages, no?

I think this is highlighted in Breen et al.’s study, in which they merge Dan McAdams’s personal narratives tradition with Gosling’s study of personal environments in the hopes that each can enhance the other’s impact. In their paper, they generally conclude that asking someone to tell stories about the things in their space can accomplish many of the same goals as McAdams’s Life Story Interview, a tried-and-true narrative method for understanding the whole person.

A brief walkthrough

I thought I’d look at this myself by providing a very brief (and very incomplete) narrative accounting of a few aspects of my office to see how much can be learned and in what manner. Without further ado, here is my office:

I have arranged nothing. This is how it appears as one walks in today, August 17, 2022. We often have limited choice as to the location of our offices in the academy, but we moved buildings in my second year, and I was able to request a window with a view of the lower quad’s greenspace.

One of the things I like about where I work is that it’s a nice physical campus, and this allows me to enjoy that as much as possible. Probably the other standout feature here is the couch, which was (once again) salvaged from deep storage in the university. What isn’t apparent about the couch is that I obtained it through my friendship and favored status with our previous departmental administrative assistant, who knew all the right people and places. The couch is exterior behavioral residue in that it is evidence of social bonds I created—something that could never be apparent without my adding narrative context. It also serves as interior behavioral residue in ways that maybe aren’t obvious: When my children were small, and I never slept at night, sometimes I would catch a nap between classes on ol’ Bessie.

Above the couch is an arrangement of nature photos. A casual observer may conclude that I am a photographer. But I am not. Those were captured by a former colleague who bequeathed them to me upon his retirement. I do love the photos, but rather than serving as an other-directed identity claim (I’m a photographer!), they are a self-directed identity claim: I like to think of the days when my friend was two doors down and remember all of our chats and musings and counseling.

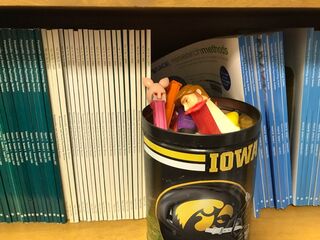

Here’s my Pez collection. Well, here’s a bucket of Pez dispensers and the yet-to-be-repurposed spice rack that will display many of them.

When people see this display, they will think that I love Pez and would like them to know that. The truth is that I loved Pez as a child and that, many years later, in my 20s, my parents bought me a Pez dispenser as a gag. Then a few more. Then other people saw them here and there and started buying me Pez dispensers.

Now I have a Pez dispenser collection. Is this even an identity claim or behavioral residue at this point? I’m not sure. But I think the story says something about me and how people relate to me.

Relatedly, you may have noticed the basketball-related paraphernalia next to the empty Pez display. I am indeed a big fan of NBA basketball. However, a naïve theory of straightforward identity claims would suggest that I am a fan of both the Sacramento Kings and the Houston Rockets. If not, why have a giant stuffed Kings bear and Rocket bobbleheads displayed?

You’ve now guessed that, indeed, I am decidedly not a fan of either organization. Rather, one of my friends from graduate school was from Houston, and we used to watch when the Rockets played my Los Angeles Lakers (from where I grew up) or Dallas Mavericks (representing where I grew up after that) and yell at each other about the contests. Later, when he and his spouse moved to Davis, California, they sent me the Kings bear to further troll me. The display of these items is again an internal identity claim, something that reminds me of two good friends, the latter of whom officiated our wedding and is also one of my favorite people ever.

All things considered

I've only covered about 10 percent of my office's contents. But I think what stands out to me is how often the story not only enriched the impression the object might create on its own but also how often it fundamentally changed the meaning of the object as it pertains to my personality.

The other thing that stories allow is for themes to emerge. In just these few descriptions, we can see I surround myself with things that are mostly for me and not for others and that these things are mostly intended to remind me of people who are important to me (I have many photos of my wife and children and various artifacts connected to all of them as well). Another theme that emerged is that I intend to organize and fix things (the light switch, the Pez display, the hanging of the Tom Waits portrait—which was also a gift from a valued friend, by the way) but sometimes (often) get sidetracked. Finally, one might have noticed that my relationships with close others often involve a sort of jovial antagonism (I think some of the Pez purchases are just to rib me).

These are nuances that capture a lot of what a Big Five Personality Test might and much more. And I found myself agreeing with Breen et al. (2021) that a longer conversation about the contents of my office might cover many of the highs and lows and changes in my life. I wonder if that’s true for everyone. What does your stuff say about you, and more importantly, what do you say about it?

References

Breen, A. V., Scott, C., & McLean, K. C. (2021). The “stuff” of narrative identity: Touring big and small stories in emerging adults’ dorm rooms. Qualitative Psychology, 8, 297-310.

Gosling, S. (2008). Snoop: What your stuff says about you. Basic Books.

Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A room with a cue: personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 379-398.