Dissociation

Dissociating is the experience of detaching from reality. Dissociation encompasses the feeling of daydreaming or being intensely focused, as well as the distressing experience of being disconnected from reality. In this state, consciousness, identity, memory, and perception are no longer naturally integrated. Dissociation often occurs as a result of stress or trauma, and it may be indicative of a dissociative disorder or other mental health condition.

Dissociation can be terrifying for those who experience it, as well as for their loved ones. But seeking treatment can help people regain their sense of self and lead a fulfilling life.

There are three main dissociative disorders, as listed in the DSM-5. They are Dissociative Identity Disorder, Dissociative Amnesia, and Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder.

Dissociative Identity Disorder is when someone’s identity is characterized by two or more distinct personality states. This discontinuity leads to a disrupted sense of self. The person may not be able to recall personal information, everyday events, or a traumatic incident. These symptoms cause significant distress in work, school, relationships, or other aspects of daily functioning. This condition was previously called Multiple Personality Disorder.

Dissociative Amnesia is when a person is suddenly unable to remember important biographical information about themselves, outside of the realm of normal forgetting. The event they can’t recall is often a stressful or traumatic one, and the experience leads to significant distress in the person’s life.

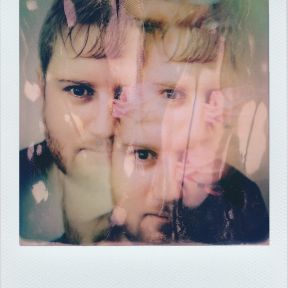

Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder is when persistent episodes of depersonalization occur—feeling a sense of unreality, detachment, or being an outside observer of one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, or actions—and/or derealization—a sense of unreality or detachment regarding one’s surroundings, such as individuals or objects seeming unreal, foggy, or visually distorted. These experiences lead to distress and impairment in the person’s life.

Depersonalization refers to feeling severed or alienated from your body. Individuals who experience depersonalization often report not recognizing themselves in a mirror, feeling like their body is not their own, or even being temporarily unable to talk. It’s the ultimate “out of body” experience. For many, there’s a sense of emotional numbing as well—feeling “meh” about things that should be emotionally intense.

Derealization is feeling isolated from your surroundings, like being in the middle of a crowded party and feeling like you’re just vaguely watching it on TV. People will often say the world looks fake, or that they are seeing it through a veil. Some say that the world loses color.

Naturally, dissociating often feels scary, especially if the experience feels profound and uncontrollable.

Children who suffer from dissociation often display symptoms that can be misinterpreted. Kids with dissociative disorders are prone to trance states or blackouts, where they become unresponsive or has a lapse in attention. They may also stare at nothing, forget parts of their life or what they were doing moments ago, or act as if they just woke up in response to being called to attention. Coupled with sudden changes in activity levels (being lethargic one minute and hyperactive the next), these symptoms are often misinterpreted as ADHD or Bipolar Disorder.

Dissociative symptoms like dramatic, abnormal changes in mood, personality, or age, acting in socially inappropriate ways, or insisting on being called by another name can lead to misdiagnoses of psychotic or behavioral disorders.

Underlying all of these symptoms is a tendency for the child to separate parts of themselves, or fragment. This fragmentation is often the result of experienced trauma, which, for children, is often abuse or neglect in the home.

Dissociating isn’t always negative. Detaching from reality can be positive, such as in a flow state, or neutral, such as when daydreaming or “spacing out” during a walk.

But in many cases, especially those in which dissociation occurs due to trauma, the experience is deeply distressing, both in the moment and in the aftermath.

Trauma is one of the central reasons why dissociation and dissociative disorders emerge. When faced with tremendous physical or emotional pain, an individual may unconsciously distance themself from the experience.

For example, dissociation is a common response to child sexual abuse. Among those with Dissociative Identity Disorder, the prevalence of childhood abuse and neglect is about 90 percent according to the DSM-5. Stress and trauma can trigger dissociation in adulthood as well, such as in the case of physical assault or military combat.

Dissociation may also be a symptom of several other conditions, including acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, personality disorders, seizure disorders, and substance or alcohol use.

Trauma is often a precursor to dissociation. The overwhelming force of traumatic events can overpower existing coping mechanisms. For those unable to physically escape, dissociation provides a psychological exit from the horror of the event. Once the traumatic experience has been dissociated from the sense of “who one is,” it is no longer considered as a self-narrative. For example, someone who was sexually abused as a child may have feelings of overwhelming shame and anger that could not be processed consciously at the time.

A pattern of abuse or trauma is one way for an isolated incident of dissociation to shift into a disorder, as dissociation becomes habitual, reinforced, and conditioned with every episode. The person may eventually dissociate automatically when a particular environmental cue or event is similar to a previous traumatic event, such as in the case of repeated parental abuse.

Dissociation can be an effective defense against acute physical and emotional pain, especially for children. A creative survival technique, it can allow an individual enduring hopeless circumstances to preserve areas of healthy functioning. When a person dissociates, some information—particularly the circumstances surrounding a traumatic event—is not integrated with other information and instead held in peripheral awareness. In that way, it is kept at a distance from the person’s immediate awareness, ideally until the time when he or she has the strength or perspective to confront the experience.

Dissociation is often treated through a combination of therapy and medication. Therapy can allow people to gradually access and consciously process the experiences during which they have dissociated. Coming to terms with that pain can liberate dissociated feelings and fully integrate one’s identity. Therapy can also help people identify and change harmful patterns of thinking and develop healthy coping skills, such as through cognitive behavioral therapy or dialectical behavior therapy.

No medications are specifically approved to treat dissociation, but antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs can help with accompanying symptoms.

With support and treatment, individuals can manage dissociation and greatly improve their daily lives.

It can be very frightening to witness a loved one become disconnected from their identity or memory. Stay with them throughout the episode, and try to help them feel grounded, such as by asking them to state where they are and what they hear, or focusing on sensory experiences such as holding a warm or cold object. Some people report that skin-brushing is particularly helpful in staying connected to their body and reducing dissociation.

If the person dissociates regularly, ask about their past experience and potential triggers so that you can be ready to help in the future, and explore whether you can help them seek mental health care.

If you have distressing episodes of dissociation, it’s important to seek help. Support and treatment is available, and finding a therapist can help begin that process. But in the moment, a few strategies can help you stay grounded:

• Engage your senses: For example, name five things you can see or squeeze an ice cube to connect to the world and your sensations.

• Pay attention to your breathing: Feel the air move in through the nose and out through the mouth.

• Focus on an object: Choose a photo, keepsake, or piece of jewelry that can help tether you to your memory and identity.

When working with trauma survivors, it’s not unusual for therapists to witness a client dissociating. The client may abruptly stop talking, break eye contact, feel frightened, or say they feel disconnected from space or time. Although therapists may be tempted to wait for the client to “come back” or avoid discussing it for fear of how the client will respond, it’s crucial to address dissociation to help the client move forward. The therapist can ask about the cues, topics, or triggers that led to the episode, and explore how to replace dissociating with healthier coping mechanisms.

Healing from dissociative identity disorder is a complex process, and certain techniques can be more helpful than others. In one woman’s experience with dissociation, six therapeutic tools proved most valuable: building trust between therapist and patient, responding non-defensively, flexible facing, exploring hypnosis to face traumatic memories without their full force, illustrating the healing process through stories, and asking the patient before addressing different personality states.