The Treatment of Anxiety

Some anxiety is part of the cost of admission to humanity. Because its distinguishing raison d’etre is the anticipation of bad outcomes, it can be a helpful stimulus to preparation or rehearsal before a significant event so as to up the odds that things will turn out the way you want. Eliminating anxiety altogether is not a desirable goal. Finding workable ways to manage anxiety and keep it from interfering with life is a skill everyone needs to have. Anxiety that hogs your mental life or curbs your normal activities demands serious attention.

On This Page

- When does anxiety need treatment?

- Does anxiety ever go away on its own?

- What are the treatment options for anxiety?

- What happens if anxiety isn't treated?

- What is the first-line treatment for anxiety?

- What does psychotherapy do?

- What does medication do?

- What types of medication are used to treat anxiety?

- How do anti-anxiety drugs work?

- How do I know which treatment is best for me?

- Are brain scans useful in determining treatment?

- How long does it take for treatment to start working?

- What are signs the treatment is working?

- How long will treatment be needed?

- Are there ways to reduce anxiety naturally?

- What's the best way to help someone who has anxiety?

- Does exercise help?

- Is it possible to be cured of anxiety?

Like every other disorder, anxiety needs treatment when, through frequency or intensity, or both, worry interferes with functioning. Anxiety encourages the maladaptive response of avoidance of uncomfortable situations, limiting experience and, often, enjoyment of life. Worries can consume an inordinate amount of time, day and night, disrupting concentration, preventing sleep, and just creating all-around suffering. And like most other mental health disorders, anxiety is isolating, discouraging the very contact that counters anxiety’s pervasive sense of threat. As a preoccupation with some imagined future bad outcome, anxiety keeps people from enjoying the present and, perhaps more cruelly, finding a solution to whatever problem is the source of worry—when, In fact, freeing up mental space to engage in immediate activities is more likely to create the conditions for resolving the worry, one of the major goals of treatment.

And yet, an astonishing number of sufferers avoid getting treatment. They often mistake the many physical symptoms of anxiety for proof of a physical disorder and pursue diagnosis of what they believe is a hidden malfunction. Or they may feel they can get a grip on their worry on their own, a grip that usually proves just out of reach. In one large study, barely 20 percent of people with anxiety disorders sought professional help.

Anxiety is a deeply rooted protective mental state essential to the survival of individuals and the species. Some anxiety is therefore necessary. Unfortunately, the neural pathways of anxiety are given to overactivity, and worst-case scenarios of possible danger ahead, dreamed up in the imagination, commandeer attention. Anxiety naturally waxes and wanes on its own, but in the absence of skills for managing worry—and especially the disquieting physical components of anxiety—it can get the upper hand. Given the natural variable course of anxiety, there may be periods when symptoms no longer meet the diagnostic criteria for disorder, but residual symptoms are still likely, as is the possibility of recurrence. There are many things to do when your anxiety won’t go away.

All patients need to be educated about the nature of their disorder and what triggers it. Beyond that basic information (psychoeducation), there are three evidence-based approaches to anxiety disorders. The first is psychotherapy, most commonly cognitive behavioral therapy, which has been found useful for generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and panic, the anxiety conditions for which most patients seek clinical help. Phobias including agoraphobia respond to a type of behavioral treatment known as exposure therapy. Psychotherapy aims not to root out anxiety—which is neither possible nor desirable—but to provide tools for calming physical arousal, correcting cognitive distortions, and decreasing the avoidance of what is feared. Therapy, however, takes time, and the distress of anxiety can be so acute that many patients seek immediate relief.

Medication is commonly prescribed alone or in combination with psychotherapy, although not all medications used to treat anxiety provide immediate relief. The most commonly prescribed drugs, SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), can take several weeks to have a noticeable effect. Benzodiazepines are also widely prescribed, and while they act quickly, they are broadly sedating. Further, they carry the risk of dependency. So-called lifestyle approaches, such as exercise regimens, breathing techniques, and mindfulness training are also important approaches to anxiety, prescribed as stand-alone measures or as adjuncts to other therapy.

If untreated, mental illness in general, and anxiety in particular, can progress in symptom severity and significantly restrict people’s lives. Untreated anxiety can lead to panic attacks, which are not only terrifying in themselves but so dramatically distressing that they strongly shape future behavior. They prompt people to curtail activity for fear of another bout of intense anxiety and to devote a great deal of mental life to plotting the possible need to escape from places that make them feel unsafe. In addition, untreated anxiety creates the risk of co-morbid depression; studies show that over the course of a lifetime, 64 percent of those with generalized anxiety disorder develop major depression.

Because anxiety shares many of the same neural pathways as pain and commonly co-occurs with it, anxiety exacerbates the perception of pain and increases the risk of disability from it. Further, anxiety activates the stress response, and the hormones of stress repeatedly batter body and brain, leading especially to memory problems due to toxic effects on the hippocampus. Anxiety typically interferes with sleep, and through chronic insomnia, untreated anxiety can undermine body systems of metabolism, raising the risk for diabetes; disrupt immune function; and chronically raise blood pressure.

But the cost of untreated anxiety on quality of life and relationships may be greatest of all. Anxiety encourages people to avoid situations and experiences that give rise to its distressing physical sensations, reinforcing the (mistaken) sense of danger. It shrinks people’s lives—one reason it so often leads to depression—and can especially rob children of important developmental experiences.

In adults, anxiety is a common cause of substance use and abuse. Studies show that a quarter of all people with anxiety are unaware they have a mental health condition; alcohol or other substances can mask the uncomfortable symptoms. Over time, anxiety affects both mental and physical health, impairing functioning to the equivalent degree of suffering from a chronic physical disease such as congestive heart failure.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is regarded as a necessary treatment for anxiety, and studies show that it is at least as effective as medication. Unfortunately, many people may not be able to focus on therapy without the symptomatic relief provided by medication. For that reason, psychotherapy is often used in combination with medication. A major value of therapy is that it helps people identity the triggers for their anxiety, an important first step in learning the lifetime skill of managing anxiety. Drugs, on the other hand, provide relief only as long as they are taken. While they carry the risk of side effects, the most commonly recommended drugs, the SSRIs, do not work immediately and don’t work at all in about a third of patients.—and only moderately in another third.

One of the paradoxes of anxiety is that the condition produces bodily symptoms that are, at a minimum, highly unpleasant but many people do not seek treatment at all. Many who do seek treatment go from doctor to doctor searching in vain for diagnosis of what they believe must be a physical disorder.

The most widely tested therapy for anxiety is cognitive behavioral therapy, a short-term, skills-based approach, It takes aim at several aspects of anxiety at once—the cognitive processes that lead to endless worry; the uncomfortable physical symptoms such as hypervigilance, racing heart, and general jumpiness; and the behavioral consequence of anxiety, such as avoidance of what is feared, which winds up shrinking life and robbing it of pleasure.

CBT teaches skills to diminish body-wide hyperarousal, such as diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation. At its heart, CBT targets distorted thoughts, such as the expectation of disastrous outcomes to future events, on the grounds that maladaptive thoughts underlie maladaptive feelings and behavior. Patients are taught, for example, to examine the evidence for and to challenge their automatic thoughts, rather than to accept them at face value. They learn to identify all-or-nothing thinking (such as, “If I don’t get into College A, my life will be ruined”), jumping to conclusions, catastrophizing from tiny bits of evidence, ignoring or discounting positive evidence, and other thought distortions that incline the mind negatively.

Anxiety is a state of mental and physical arousal, manifest in hypervigilance, inability to concentrate, and general jitteriness, among other symptoms. There is no one specific type of agent to resolve anxiety, because the condition is complex and involves many systems in the brain and body. In fact, the nature of anxiety and the circuitry of the brain that it utilizes is still very much under active scientific investigation. Nevertheless, there are several different types of medication used to treat anxiety. In general, medication aims to calm the nervous system. Often, medication is used to help lower levels of anxiety enough so that patients can focus attention on and get the benefits of cognitive behavioral therapy. It may take trials of more than one drug to find the best anxiety-reducing medication for any patient.

There are several types of anti-anxiety drugs doctors have at their disposal to help patients. The first such drugs to enter the anti-anxiety arena were the benzodiazepines Librium (chlordiazepoxide) and Valium (diazepam), in the early 1960s, later joined by such agents as Xanax (alprazolam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin (clonazepam). They are all tranquilizers and have a general sedating effect on mind and body. They work quickly and can relieve the acute anxiety of panic attacks. But they can also create dependency, and, although they are still in wide use today, they are considered best for short-term use.

Another group of drugs, developed in the 1960s, are the so-called beta-blockers, such as propranolol, which are perhaps best known for treating abnormal heart rhythms. Although they are not officially approved for use in anxiety disorders, there is significant research supporting their use as needed to help individuals who suffer from performance anxiety get through stage fright, and there is evidence they improve the performance of musicians when taken before a performance.

The most popular anti-anxiety drugs in use today are the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), first introduced with Prozac (fluoxetine) in 1988, and their siblings, the SNRIs (selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors). Generally regarded as antidepressants, they also help relieve a wide array of anxiety and anxiety-related disorders, including generalized anxiety, panic disorder, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and PTSD. It is not clear why they work against anxiety, but both anxiety and depression involve many of the same neural pathways in the brain. They are often used along with psychotherapy. Typically, SNRIs are used if a patient fails to respond to an SSRI. It is a topic of considerable controversy, but much of the response to SSRIs is believed to be due to the placebo effect.

There is no one pathway or mechanism by which anti-anxiety drugs work; each group of chemically related agents takes a different approach to some characteristic of anxiety. The benzodiazepines, for example, are sedating agents that affect the whole body, promoting relaxation and reducing muscle tension, which is why they are also often given prior to surgery. The benzodiazepines boost levels of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a neurotransmitter that is widely distributed in the brain and puts a brake on the firing of neurons; it tamps down the nervous system in general. Because they act quickly but can create dependency, they are sometimes used in the early weeks of anxiety treatment, until other agents achieve their effect, after which their use is tapered off. As central nervous system depressants, benzodiazepines can impair driving and cognitive functions such as memory.

Beta-blockers are so-called because they block a group of receptors for the neurotransmitters epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), which mediate the flight-or-fight response. The agents control such performance-disturbing symptoms as racing heart, rapid breathing, sweating, and shaking and can be helpful when taken shortly before a performance.

SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) target receptors for the neurotransmitter serotonin, while their siblings the SNRIs target receptors for both serotonin and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). They block the reuptake of the neurotransmitters at nerve-cell junctions, increasing levels of neurotransmitters to facilitate the transmission of nerve impulses. Serotonin is known to be involved in mood, while norepinephrine mediates the stress response, a component of anxiety.

While both drugs are typically used in higher doses in anxiety than in depression, they are started in low doses and can take four to six weeks to reach maximum impact. It is thought that their ultimate effect is to create neuroplasticity in the brain, stimulating the growth of new neurons that underlie increased behavioral flexibility. Among the most commonly used SNRIS for anxiety are Effexor (venlafaxine) and Cymbalta (duloxetine).

The treatment of anxiety is both an art and a science, depending in large part on which of the many symptoms of anxiety are most prominent and most troubling in each affected individual. In many patients, anxiety is accompanied by depression, a diagnosis that mitigates again the use, for example, of benzodiazepines and for the SSRIs or SNRIs. In addition, the choice of drug is influenced by the profile of side effects it is associated with, possible interactions with other medications a person may be taking, and general health status.

Because of the many variables physicians must weigh in deciding on a drug and measuring its effectiveness in each individual, some degree of trial-and-error should be expected. Clinical psychiatrists who are highly experienced in treating anxiety disorders have a general sense of which symptoms, and which clusters of symptoms, may respond to which drugs. Still, more often than not, it takes a trial of one or more agents to find the most effective one, or combination of drugs, and the most effective dose, with the fewest, or most tolerable, side effects.

Brain scans have been very helpful in research to identify brain regions that are key to processing emotional stimuli and circuits of neural communication that malfunction in anxiety. This information helps researchers assess the mode of action and effectiveness of drugs in development. It is also used in studies of the effectiveness of psychotherapy, to assess brain function before and after treatment.

But neuroimaging remains primarily a diagnostic and research tool, and a costly one at that. And while it is helping identify nerve circuits involved in distinct clusters of anxiety symptoms, and especially in distinguishing how the brain processes anxiety versus fear—information that enables researchers to identify promising targets for drug intervention—such use is very much in the research realm. In general, scanning does not yet provide enough specificity or utility for personalizing therapy.

Benzodiazepine drugs, given for generalized anxiety and panic, can produce a noticeable calming effect almost immediately—within an hour. But because of their ability to create dependence, they are recommended primarily for use short-term, sometimes along with SSRIs before their effects kick in.

Beta-blockers also work almost immediately against the physical symptoms of anxiety and are usually taken just before a speech or performance to curb stage fright or performance anxiety.

For longer-acting agents, depending on which medications are used, it can take two or more weeks to feel any relief from anxiety and six weeks or more to feel significant relief.

SSRIs and SNRIs affect neurotransmitter levels rapidly, although those effects are not directly responsible for symptom improvement, which takes time; the agents generally take several weeks to produce any reduction in anxiety symptoms and several weeks more to exert maximum effects. Research shows that is the time needed for neurons to grow and rewire the brain.

The first signs of relief may be moderation of the physical symptoms of anxiety, such as reduction in muscle tension and headaches. However, there is the possibility that such symptoms as jitteriness will increase in the first week or two. With benzodiazepines, people may also experience a speedy reduction in worry, or rumination over possible undesirable outcomes ahead. The anxiety relief usually lasts no more than a few hours.

For people taking SSRIs for anxiety, it can take more than a month for effects to kick in, but those who respond often report that their anxious thoughts are less insistent, and that they are able to engage with psychotherapy. Studies show that 40 to 60 percent of patients treated with an antidepressant experience an improvement in symptoms within six to eight weeks.

Care standards specify that once patients experience a reduction in anxiety symptoms with SSRIs or SNRIs, treatment should be continued for at least six months. In contrast to use of psychotherapy, where gains are maintained for months and even years after treatment ends, patients typically relapse immediately after stopping medication. Relapse prevention studies, in which patients are randomly assigned to receive a drug to which they previously responded or a placebo, show a significant advantage for staying on active medication. Based on such studies and widespread clinical experience, as well as the chronic nature of anxiety disorders, experts recommend that drug treatment be continued for 12 months or more after remission has occurred, although there are few studies of long-term anxiety treatment. When drugs are stopped, the dose should be slowly tapered off.

There are three extraordinarily effective way to moderate anxiety without the use of medications. All are simple lifestyle modifications. The first and most accessible is deep breathing, or so-called abdominal breathing. It can be done anytime, anywhere, and requires no special equipment of any kind. Taking deep breaths that fill the lungs and then exhaling slowly through pursed lips stimulates the parasympathetic nerve, directly countering the stress response and inducing a state of calm. Heart rate slows, blood pressure falls, muscles release tension.

Physical activity is another highly effective antidote to anxiety. It has a number of direct and indirect effects against anxiety. It stimulates neuroplasticity, which ultimately restores behavioral flexibility and pathways out of rumination and worry. It also counters the physical components of anxiety, decreasing muscle tension and dissipating the effects of stress. As little as 30 minutes of walking three times a week activates the frontal lobes of the brain, restoring executive control over the amygdala and over reactivity to real or perceived threats. And while exercise is a distraction from worry, its most important psychological benefit may be that it restores a sense of control in a condition that can feel beyond control.

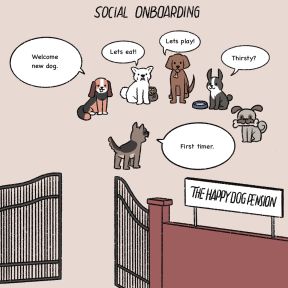

A third natural antidote to anxiety is the value of companionship. Physical contact restores sense of safety, countering the sense of threat that characterizes anxiety. Not least, play is the antithesis of anxiety. Any activity that involves play—whether tossing around a ball with kids or friends, engaging in board games with a partner, or doing crossword puzzles by oneself provide relief.

Let’s be clear: Saying “Don’t worry” is never helpful to someone with anxiety, whose brain simply can’t turn off the worry. The very best way to help someone who is anxious is to get them to a therapist for treatment. Another important step is to support regular physical activity. It is one of the most effective remedies for anxiety, yet there is evidence that those with anxiety are more sedentary than others. Better than reminding someone to get exercise is handing them a jacket and taking them out for a walk. Both the exercise and the companionship have direct anti-anxiety effects. So does the change of scenery. Maintaining social contact with someone who is anxious is vital. Anxiety is a disorder of perceived threat. Companionship restores a sense of safety.

Exercise may be the single most effective remedy for anxiety. It is one of the most effective ways to jump-start neuroplasticity—the exit ramp from anxiety as well as depression. Numerous studies show that engaging in simple activity such as walking immediately stimulates the growth of new nerve cell connections, the foundation of neuroplasticity. Exercise appears to especially increase neuroplasticity in the hippocampus, a center of learning and memory and an area of the brain especially vulnerable to the disruptive effects of stress, a component of anxiety. In addition, weight training, or resistance exercise, has been shown to increase the signaling power of nerve cells. Exercising for at least 30 minutes a day three to five times a week has been found to be of benefit.

In addition to the direct effects on the nervous system, engaging in any form of exercise restores a sense of control over one’s life. Studies show that even 15 minutes of physical activity daily—especially in the afternoon—can have beneficial effects. Exercise also provides anxiety relief by serving as a diversion from worries, but that’s the least of it. It dissipates the muscle tension that is among the most prominent of the physical symptoms of anxiety. And it activates the frontal lobes of the brain, restoring executive control over the amygdala and reactivity to real or perceived threats.

All evidence indicates that anxiety disorders run a chronic course. However, symptoms tend to naturally fluctuate in severity, and there are periods of relapse and remission, particularly in generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. By contrast, symptoms are usually more chronic in social anxiety disorder, until age 50.

Patients maintain a fear of being the center of attention or talking to authority figures. In fact, generalized anxiety is the only anxiety disorder that is still common in people 50 years or older. It is neither possible nor desirable to eliminate the capacity for anxiety from human experience. Psychotherapy has been rigorously tested and found to deliver important skills for managing anxiety over the course of a lifetime.