Media

How Our Tendency to See Patterns May Lead People to Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories can be very tempting when we connect the dots.

Posted September 27, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Conspiracy theories are often presented compellingly, taking advantage of our tendency to see patterns that may not exist.

- When we encounter limited information that leads to a conclusion, we will very likely see the pattern and connect the dots.

- People who believe conspiracy theories may have seen limited information that leads to a claim consistent with their worldview.

When I was a kid, I loved doing connect-the-dots drawings. I enjoyed discovering a pattern. Those who suggest conspiracy theories know the brain's natural ability to find patterns. They know that just a little information will be enough for us to connect the dots.

Conspiracy Theories as Connect the Dots

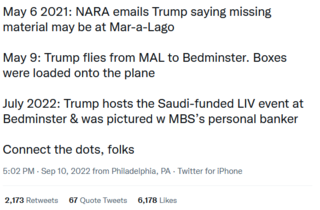

When people suggest conspiracy theories, sometimes they don’t state the conclusion directly. Instead, someone will put together a list of statements–maybe even true statements. Then they encourage you to come to your own conclusion. For example, consider the tweet in the picture. In this example, the person provided three claims. These claims may be valid. The writer then encouraged us to "connect the dots."

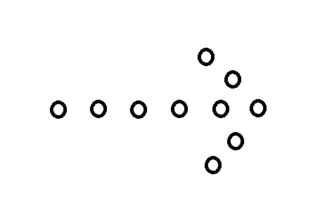

In essence, they have drawn an arrow pointing to a particular conclusion. Maybe it’s a conclusion you like. Perhaps you think it implies something ridiculous. Either way, you are being led to a particular conclusion.

If you are on social media or watch news media, you will routinely be exposed to this type of presentation. We are all at risk of following the set of information to the implied conclusion. It is like a connect-the-dots arrow being drawn pointing to a single and obvious conclusion. Yes, I can connect the dots. I see where you are leading me.

Illusory Correlations and Finding Patterns

People are great at seeing patterns. We’re so adept at finding patterns that we can see patterns even when none exist. This is the nature of cognitive processing that leads us to illusory correlations.

An illusory correlation is a belief that two things go together when they are not associated (Chapman, 1967). For example, many people believe that people riding bicycles break more rules of the road than people driving cars. But as has been documented in multiple data collection projects in different locations, cyclists are less likely to break laws. Why do we believe cyclists flout the rules of the road? Illusory correlations may contribute.

We constantly search for patterns. Cyclists stand out because they remain rare compared to car drivers. When a cyclist breaks a rule, it will be easy to notice and remember. Thus, we can put these two things together. But we don’t notice or count the cyclists who obey the road rules or the car drivers who break road rules. We see a pattern, but that pattern doesn’t exist: It’s an illusory correlation.

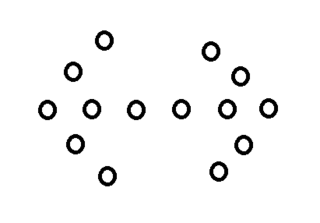

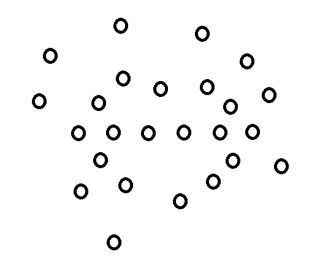

As pattern seekers, we can be susceptible when someone shows us partial information that points to a particular conclusion. They have given us dots, and we connect them. This is most effective when we are only given limited information. More information shows us that the conclusion may point in either direction. And with a full set of information, it may be hard to discern any pattern.

Worldviews and Conspiracy Theories

But another aspect of conspiracy theories can make them particularly enticing. The conclusions we are asked to consider may fit our belief structure and worldview (Hyman & Jalbert, 2017).

Perhaps when you considered the Tweet about Donald Trump and documents, you found the argument compelling. It may be consistent with your beliefs about the former president. You may find it emotionally satisfying. On the other hand, maybe you didn’t find it believable–you don’t think it is consistent with something that Trump would do. Either way, this conspiracy theory either is or is not consistent with your beliefs and worldviews.

We are more likely to believe and remember information that is consistent with our beliefs. If the pieces of a conspiracy remind you of things you know and believe, you’ll nod as you hear about those claims. Encountering ideas that fit with your existing knowledge can help you remember new information–even if that new information isn’t leading you to the truth.

The Appeal of Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories can be compelling and easy to remember. When we have a limited set of facts and can create conclusions from the implications, we are likely to both remember and believe that conclusion. When that conclusion is consistent with our worldview, we are more likely to remember and accept the suggestion.

People who believe conspiracy theories have seen limited information that leads to a claim that fits their worldview. This is something that we all can experience. Conspiracy theories can be very tempting when we connect the dots.

References

Chapman, L. J. (1967). Illusory correlation in observational report. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(1), 151-155.

Hyman, I. E., Jr., Jalbert, M. C. (2017). Misinformation and worldviews in the post-truth information age: Commentary on Lewandowsky, Ecker, and Cook. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6, 377-381.