Mating

New Details Revealed About an Important Human Ancestor

A big announcement from South Africa about Homo naledi.

Posted May 9, 2017

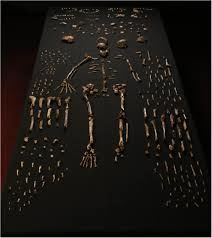

In September of 2015, scientists at the University of Witwatersrand, led by Dr. Lee Berger, made a bombshell announcement. Not only had a new species of hominin been discovered, but the find contained more than 1,500 fossils from at least 15 individuals. The remains were found all in one place, a deep dark cave in South Africa. This was, by far, the largest number of fossils ever found in one place in the history of paleoanthropology.

In one full swoop, Homo naledi went from being completely unknown to us to being one of the most fully described hominins of all. Although no age was given to the fossils at the time, speculation was rampant.

The big news in the world of paleoanthropology today is that the recently discovered H. naledi is a lot younger than previously thought, and a second cave of fossils has been found. I caught up with Lee Berger last weekend to ask him what all this means.

Over the last few months, the paleoanthropology community has been abuzz with rumors that more H. naledi fossils had been found and that the age of the fossils had been determined. On May 9th, a huge team of scientists, again led by Berger, confirmed the rumors and made two big announcements regarding this enigmatic species. First, a second cave had been found harboring more H. naledi skeletal remains. Second, and even more dramatically, the dating effort from the original fossil find revealed that the fossils are much younger than previously thought, a mere few hundred thousand years old.

The results are released in three papers in the journal eLife, published by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which was also the venue for the first publication of Homo naledi in 2015. Both of these announcements have astounding and far-reaching implications.

The Second Cave

The second cavern, called the Lesedi chamber, is a mere 80 lateral meters from the now-famous Dinaledi chamber, which housed the treasure trove of fossils announced in 2015. That find remains the largest hominin discovery in history with enough fossils to nearly recreate the entire skeleton. Both the Dinaledi and Lesedi chambers are within the Rising Star cave system in the UNESCO World Heritage Site called The Cradle of Humanity.

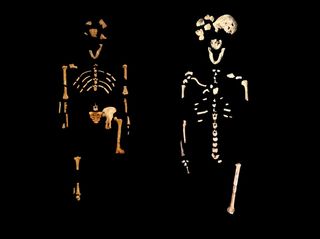

The Lesedi chamber contains fewer fossils than were in Dinaledi. However, while the Dinaledi fossils were all mixed in together, Lesedi harbored partial skeletons corresponding to three distinct individuals, two adults and an infant. One skeleton, called Neo, is nearly as complete as the "Lucy" skeleton, possibly the most famous ancient skeleton in the world and the type specimen of Australopithecus Afarensis.

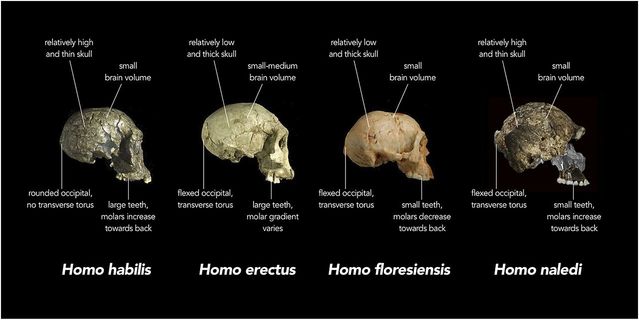

The remarkably complete skull of Neo adds additional information about the anterior skull and face. For example, we now know that the nose and maxillary area of naledi is flatter than previously thought. "Hopefully this puts the argument that this is Homo erectus to rest!" said Berger, a reference to the small but vocal contingent of those that believe that naledi is nothing more than a ‘primitive H. erectus.’

Both of these “burial chambers” are in the same cave system and both are incredibly difficult to access. All assumptions are that the hominins in both chambers were contemporaries, but the age of the new fossils is not yet known. Dating will require that some fossils be destroyed in the process, and Berger insists on publishing the fossils first and making them available to the community via Morphosource before any of the samples are consumed for the dating efforts. As I wrote in Skeptic Magazine last year, the H. naledi team has displayed an unprecedented commitment to transparency and the democratization of science, believing that fossils belong to no one and should be shared freely and widely.

The surprising young age

When H. naledi was first announced, many assumed that the fossils were between two and three millions years old. The unique and surprising combination of primitive and advanced features places this species at or near the base of the Homo family tree. The tiny brain and curved fingers, for example, are primitive characteristics within the hominin lineage, but the heel made for striding, the proximal femur, and the shoulders are clearly derived features for the Homo clade. (A clade that needs some revision, by the way.)

Based on the anatomy, most agree that naledi is an early species of the Homo genus, so the tender young age of 300,000 years is quite a surprise. While there are several possibilities, what seems most likely is that this hominin was a long-persisting species. It evolved somewhere in Africa, possibly from a common ancestor of Homo habilis or even from habilis itself.

For comparison, H. erectus was also a long-persisting species, but it was more advanced than naledi, was spread throughout Asia (but not much in Africa except its earliest beginnings), and showed a steady increase in brain size over the life of the species. H. naledi seems to be more in the style of Homo floresiensis, the "hobbits" who maintained a primitive hominin form until surprisingly recent times. The hobbits had the benefit of isolation on a Pacific island, however, while naledi lived in the aptly named cradle of humanity amidst several lineages of hominins, including our own.

Whether or not naledi was long-persisting or evolved more recently from some ancestor waiting to be discovered, this adds yet another lineage of hominins roaming through the Southern half of Africa during the Pleistocene and late Pliocene epochs.

The importance of the skeleton

Hardly a new lesson, but one of the most important precepts gleaned from the bones of Homo naledi is that attempts to infer ancestry from isolated bones, fragments, or dentition must be viewed with a grain of salt. The history of paleoanthropology is filled with tall tales woven from the fragments of a mandible, a single tooth, or a piece of skull. As Donald Prothero told me when we were discussing one of his books two years ago, "That would never fly in any other field of paleontology, but when it comes to the hominin fossil record, it's us that we're talking about, so the rules get bent a little bit in our desperate desire to understand our origins."

With these two big discoveries of H. naledi and other recent finds including H. floresiensis from Indonesia, the Dmanisi skulls from Georgia, and the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain, paleoanthropology has a lot more material on which to base our still-murky understanding of our evolutionary origins. As Berger told me, "We used to joke that paleoanthropology had more practitioners than fossils, but finally that's not true anymore!" The power of having so many naledi fossils cannot be overstated. We now have an essentially complete skeleton that harbors an interesting but confusing mosaic of primitive and derived characteristics.

"The phylogeny works out very differently based on which anatomy you consider," says Berger, a point made very clear in an accompanying paper discussing how naledi fits into the rich hominin diversity of subequatorial Africa. Looking only at the skull, naledi looks primitive indeed, and this is why having the postcranial skeleton is so important. In addition, by having so many individuals, we also gain a sense of the interpersonal variation in their anatomy. From even just the first cave, we now have more fossils of naledi than we do of any other extinct hominin except Neanderthal and erectus.

Big implications for archaeology

When I inquired as to the largest impact that might not be immediately obvious, Berger replied, "The field that will be most impacted by the young age of naledi may actually be archaeology!" This is because, previously, stone tools that were found anywhere in Southern Africa dating to the middle or late Pleistocene were attributed to the coastal populations of archaic Homo sapiens. By the last half-million years, there were no other hominins in Southern Africa except our lineage. Or so we thought.

It is not known whether naledi crafted tools. When asked if any artifacts had been found in the caves, Berger demurred but did not issue a definitive 'no.' While the small brain of naledi might make it seem unlikely to be a stone tool-maker, recall that two million-year-old Homo habilis remains are associated with simple stone tools and their brains were only slightly bigger than those of naledi. It is also worth noting that the long fingers of naledi are ideal for fine handiwork.

Further still, size is only a crude measure of the power of a brain. After all, our own brains have shrunk by 10% since the last ice age. Analysis of the naledi skull has provided evidence that their brains may have undergone substantial organization and specialization like the brains of our immediate ancestors did. Because of how energy-hungry brains are, adaptations that allow greater efficiency and computing power without growing larger would be heavily favored. With this in mind, it is wise not to underestimate the brain power of the diminutive naledi.

More evidence for deliberate body disposal

Perhaps the most controversial and interesting feature of the naledi discovery is the manner in which the remains have been found. The two caves contain homogeneous collections of this single species. The only other fossilized remains are those of an owl and a few small scavenger mammals that found their way into the caves. Such mono-specific collections of remains are most unusual in paleontology, even unheard of, except in the case of a sudden catastrophe like a volcanic eruption. In these two caves, there are many individuals of the same species, with no other species present, collected in a tight space that is extremely inaccessible. This is remarkable and calls for an explanation.

From the first announcement of the dinaledi chamber in 2015, the possibility of intentional body disposal has hung in the air. On the one hand, the evidence is circumstantial and it may be impossible to ever know for sure. On the other hand, no alternative explanations supported by evidence have emerged in the last eighteen months, and surely not from lack of attention. "It's getting harder and harder to deny that the only reason we have a hard time accepting [the notion of intentional body disposal] is because we just don't want to," says Berger. Indeed, the idea that an otherwise primitive hominin might have developed enough social complexity to care about disposing of their dead is jarring, to say the least.

Even among those who agree that deliberate disposal is the most likely explanation, there is disagreement about whether this implies great social complexity. If a population was firmly rooted to a specific location, disposal of decomposing bodies could have become a simple "housekeeping" behavior to keep the area tidy. One problem with this idea is that sedentary homesteading is not a lifestyle found in any primates (except fully modern humans).

Further, the chambers are very far from the cave opening. Even if simply tossing a dead body down a hole doesn't require much intelligence or social complexity, that's not what occurred with these naledi collections. To reach either of the caves, one must traverse 60-70 lateral meters and descend almost as many vertical meters of treacherous terrain, in complete darkness. Both caves require passage through gauntlets, extremely narrow passages of 18 cm and 25 cm, respectively, at their narrowest point. Most humans cannot fit through these passages and Berger himself got stuck for some time in 2014. Geologists are quite confident that the caves were no more accessible 300,000 years ago than they are today. Whoever put those naledi bodies in those caves went to great lengths to do so. This makes little sense if the only goal was getting rid of a rotting corpse.

Fire lighting the way

While most attention understandably focuses on the body disposal itself, not to be forgotten is that both chambers were well into the "dark zone" where whoever deposited those naledi bodies was working in the complete absence of light. This suggests, though indirectly, that Homo naledi had mastered the use of fire. How else but with torches could they have navigated the twists, turns, drops, and climbs of the Rising Star caves?

Acknowledging this, Berger confirmed that scientists are scouring the cave for signs of fire use and any other artifacts that might give clues as to how and why these remains ended up in the chambers.

Something tells me that the Rising Star caves haven't given up all of their secrets yet.