Anxiety

Thoughts and Fears

Scary times don't mean we have to be scared all the time.

Posted April 1, 2020

These are scary times, but it does not mean we have to be scared all the time. What? You’re probably thinking that’s a contradiction and I’ve been cooped up in my house too long and have lost my mind. But hear me out, please. We’re going to look at this objectively rather than emotionally.

Yes, these are scary times. And, we have to be alert and vigilant. But, we don’t have to be scared.

Alert means we are aware and attentive. We gather information, use that information to protect ourselves and others, and prepare accordingly. And, it is possible to do this without being anxious.

Scared means we’re frightened, anxious, worried, our body is having a physiological reaction to the current events. But do we need this reaction to stay safe and healthy? If your fire alarm goes off in your house, what do you do? Most likely you turn it off, assess the danger, and take action, i.e., change the battery or get everyone out of the house and call the fire station. The alarm alerts you to take action. Do we need the alarm to continue ringing all the time to remind us after we’ve already taken action? Think of the anxious response as being like an alarm in our minds.

Anxiety is an emotional response to a perceived future threat. That’s important to understand. We become anxious when we think something is going to threaten us in the future. And while the perceived threat hasn’t happened yet, we worry about it now.

It’s perfectly normal to be anxious at a time like this, but ruminating about the what-ifs that may or may not happen in the future can be overwhelming and create more catastrophic thoughts and thus more anxiety. Before we know it, our imagination spins out of control and we begin to focus on the worst that could happen rather than on what we need to do right now. It’s as if we’re saying, “I don’t know what’s going to happen, but all I’m thinking about is that it’s going to be terrible.”

Let’s look at what happens in our body when we’re scared and anxious. When we have a thought that we are in danger, a signal gets sent to the amygdala, a part of the brain that plays a crucial role in the processing of fear. It then sends signals to other parts of the brain that trigger the “fight/flight” response. It does this automatically, involuntarily and rapidly in order to protect us. The fight/flight response then creates a surge of adrenaline in our body which in turn causes the heart to pump more blood into our muscles so that we’re stronger and more energized in order to fight the attacker or quickly run away from it.

In summary: We have a thought that we are in danger, it leads to the brain, causes the body to go into fight/flight response, we get a surge of adrenaline, the body gets pumped up, and we have a ton of energy floating around in our body to use for fighting and/or fleeing.

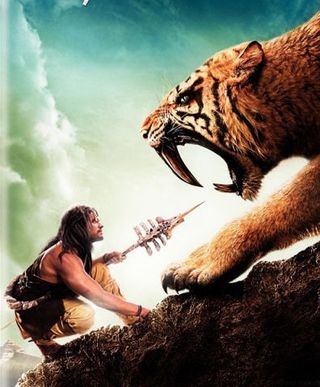

What happens to all that energy floating around in our body? The fight/flight response was lifesaving back in the day when the saber-toothed tiger had thoughts of having us for lunch. But that isn’t the case anymore. Are we going to punch the coronavirus? No, so we have the adrenaline causing our body to rev itself up, our heart to race, our blood to feverishly pump, and no way to release the energy it causes. So we feel very uncomfortable and jittery.

What can we do? Well, let’s go back to a few paragraphs above to find out. How did this cycle get started in the first place? We had a thought that we were in danger. Which was probably followed by a thought that we and/or people we love are going to get sick. Which was probably followed by a thought that we won’t be able to protect them. Which was probably followed by a thought that we might lose our jobs. Which was followed by the question of how will we pay the bills? And the thoughts can go on, and on, and on until they spiral out of control.

If the process starts with a thought, what would happen if we changed the original thought? If we don’t need the fight/flight response to protect us from coronavirus, then we don’t need the physiological response that’s caused by worrying about future events. What do you think would happen physiologically if, when we begin to worry about the future, we changed that thought to “well there isn’t a saber-toothed tiger looking to have me for lunch so, I don’t need the fight/flight response, the coronavirus is bad and scary, and because of that, I am doing everything I possibly can to control what I can control”?

If we stop our thoughts about bad things happening in the future, we will be able to focus on the here and now, the present moment, what is right in front of us. And, if there is nothing to be afraid of in the present moment, we’re OK. Remember, anxiety is always about the future.

As we take steps to protect ourselves physically, let’s also take steps to protect ourselves emotionally. The two are equally important. Below are some suggestions as to how to do this:

- Stay informed but limit your news to only legitimate sources, like the CDC or WHO. Turn the news off when it gets to be too much. You may notice that everyone on Facebook has now become an epidemiologist. Don’t listen to those people. Stay informed but don’t spend your day listening to news.

- Stick to your everyday routine as much as possible.

- Keep to your usual bed and wake times.

- Get some fresh air and sunlight.

- Find ways to exercise when you can (YouTube has exercise classes for all tastes and levels).

- Identify what triggers your anxiety.

- Stay connected with family and friends by telephone, email, zoom, etc. Schedule virtual parties, book groups, cocktail parties.

- Use your stay at home time to do things you’ve been wanting to do, i.e., books, movies, music, learning.

- Focus on the things you can control, i.e., social distancing, hand washing, getting enough sleep, etc.

- Write down specific worries you may have along with concrete solutions to them.

- Don’t self-medicate. Try relaxation exercises and/or meditation.

Remember, we don’t need to be scared to take action and be cautious. Stay healthy and well.