Pornography

Why Do We Hate Porn So Much?

Our dislike of porn may extend from longstanding sexual dualism in the West.

Posted February 13, 2019

Busy pink retail displays, children working diligently on store-bought tokens of affection, and Facebook ads burgeoning with flowers and lingerie: Valentine’s Day is upon us once again. Of all the Western holidays, February 14 is perhaps the most relevant for me, as this holiday comes close to publicly acknowledging and celebrating sexuality. More than that, though, its origins as a Roman fertility festival and its subsequent whitewashing by the Catholic Church reminds me of a more general sexual dualism in the West: Sex is simultaneously exciting, pleasurable, and generative, but also dangerous, damning, and deeply shameful.

I find that incredibly fascinating.

As a social scientist who studies porn, I’m often contacted around Valentine’s Day by journalists or bloggers looking to do a piece on sexuality. This year, an intrepid student reporter from the local university paper wanted to know about how porn impacts relationships. What struck me about this interview was not the topic—after all, I wouldn’t have a job if people didn’t want to know about these things. Instead, a single question caught my attention. Paraphrasing a little, the reporter asked me why we often assume that porn is a problem. I didn’t say it at the time, but I was impressed: In all the interviews that I’ve given and all the classes I’ve taught, I’ve never been asked this before.

At its core, this question really speaks to why I do what I do. Many years ago, I happened to take an introductory course in human sexuality. I was in a forensic science program at the time, but I was looking to expand my horizons. As part of a term assignment, I had the opportunity to read some of the academic literature concerning pornography use. I was amazed at how inconclusive much of the research was. Is porn addictive? Does porn contribute to the devaluation of women or contribute to sexual violence? Does porn destroy relationships? We don’t really have firm answers to any of these questions. The discrepancy between public rhetoric about the harms of pornography and convincing empirical evidence for these claims was so great that it made me reconsider a career in forensics.

So then, why is it that we tend to assume that pornography is harmful? The most obvious answer is that pornography actually is harmful. As Arizona state Rep. Michelle Udall recently reminded us, “pornography is a social toxin that destroys families, damages children, harms women, and creates violence.” Certainly, if you read through the empirical literature with an uncritical eye and ignore contrary evidence, it’s easy enough to justify this position. Indeed, recent meta-analyses have indicated that pornography is implicated in sexual aggression as well as sexual/relationship satisfaction. Despite the seeming piles and piles of research in this area—we’ve been at it for about 50 years—I remain largely agnostic when it comes to many claims about pornography. Hopefully you’re wondering why I don’t find much of this evidence compelling. If so, you may be happy to hear that over the coming months I’ll be making an effort to defend this position more thoroughly. For now, I hope it suffices to say that this area of study is quite complex, not particularly known for its methodological rigor, and clearly influenced by political and moral positions concerning pornography.

Independent of whether or not pornography actually contributes to personal and social harm, I think that there are probably several factors that influence our perceptions of its harm. With some notable exceptions, public discussions of pornography use, particularly male solitary use, tend to focus on the negatives. If you accept the notion that pornography impacts people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, you should at least consider the possibility that your exposure to negative media (or personal) discussions about pornography may influence your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors concerning pornography use. If you hear day after day that pornography is harmful, you may come to believe that there’s a problem.

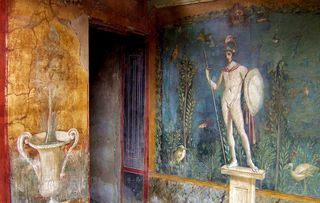

Judeo-Christian morality has also long contributed to negative views towards recreational sexuality. As best we can tell, the pre-Christian Roman Empire was replete with sexual and outright pornographic representations—for examples, Google “Pan and the Goat”—many of which were displayed prominently in public places. If you think that porn is everywhere now, you may want to read a little bit about what was found in the ashes of Pompeii. With the rise of Christianity, many of these sexual artifacts were censored by artistic license (genitals were reduced in size or covered with fig leaves), or were destroyed outright if they couldn't be easily modified, leaving us where we are today. It is now fairly well established that Western religiosity is related to more negative attitudes towards pornography, including firmer beliefs about its harms.

Of course, there are other sources of anti-pornography morality. In the 1970s, the political struggle for gender equality gave rise to a radical form of feminism that offered a new perspective of pornography. During this time, some activists and scholars began to argue that pornography was a social ill, not because it incited lust (and related sin) but because it commodified women, reducing their value to their apparent sexual characteristics. Thanks to such efforts, it is now commonly believed that pornography is a product of patriarchy that reinforces the subjugation of women and contributes to sexual violence.

More recently, growing concerns about sex and pornography addiction (which are controversial diagnoses) have spawned a lucrative treatment industry. While undoubtedly well-intentioned, those who offer such services have an economic interest in convincing you that porn is everywhere, that it is more addictive than cocaine and heroin, and that its use will eventually destroy your life. Under these circumstances, it’s hard to imagine that any of these service providers would have positive things to say about pornography.

So, there are probably lots of reasons to believe that porn is problem, whether or not it actually is. What I think connects all of these harm-based perspectives is the common view that pornography is both attractive and dangerous. Now, people who know me will tell you that I’m not a huge fan of tradition. For this reason, I’d like to suggest that just this once, we try to disrupt this sexual dualism. Tomorrow, on Valentine’s Day, let’s all adopt a new perspective on pornography, one that acknowledges the potential for harm, but at the same time, considers its potential benefits—and yes, there are some potential benefits: Users (and their partners), consistently tell us that porn helps them learn about sex, particularly their own likes and dislikes, that it helps them feel more comfortable with their own sexuality and the sexuality of others, that it can spice up a stale love life, and that it can improve sexual communication and, consequently, closeness with a partner. If you know that your partner uses porn, and you’re open to the idea, consider asking your partner to share their favorite porn with you tomorrow. You might just learn some interesting things about one another that could improve your relationship.