Grief

Drawing Out Grief

A new memoir explores girlhood friendship, hippie parenting, and buried grief.

Posted June 18, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

By the Forces of Gravity (Hippocampus, 2018), a new hybrid cartoon/free verse memoir by Rebecca Fish Ewan, explores childhood friendship and grief in hippie-era Berkeley with a unique and raw power.

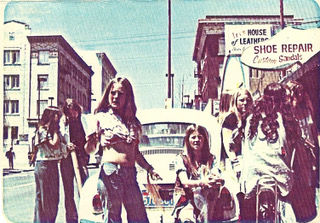

In an era of laissez-faire parenting, Rebecca drops out of elementary school and takes up residence in a kids commune—no parents allowed! We follow her, bestie Luna, and their boho pals as they search for love, acceptance, and cosmic truths in a violent world.

I asked Rebecca to share her insights on using drawing and writing to process traumatic experiences.

Whatever the cause, I get overwhelmed by sensation and drawing helps me filter sensations. Drawing does what my neurons can’t. So does writing.

—Rebecca Fish Ewan

Ariel Gore: How does art—writing and drawing—help you work with grief?

Rebecca Fish Ewan: Drawing and poetry are both immediate and visceral. They can reach grief directly and bring it out in a pure form. Not polished with heady reflection. For this story, I needed rawness. Drawing has always been my way of processing my feelings. In the sixties and seventies, kids like me were called sensitive. Nowadays there are more clinical terms for the way my brain works, based on theories about mirror neurons, serotonin, sensory filters and so on. Whatever the cause, I get overwhelmed by sensation and drawing helps me filter sensations. Drawing does what my neurons can’t. So does writing.

Sometimes I wish my work was less cartoony or that my impulse for humor was less pronounced. But not really. I just get bummed that cartoons and humor are often misinterpreted as superficial renderings, not edgy or gritty enough to be real. As if only super dismal stories can be meaningful. But maybe the best vehicle for driving into hell is a clown car.

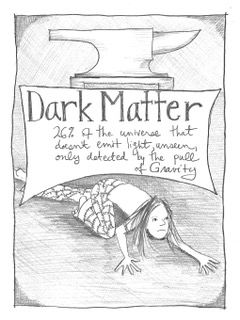

In terms of the drawings in the book, they both process and convey grief. There is a concept called re-grieving, the idea that grief is not a thing gotten over, but rather becomes a part of your being. Processing grief is not about overcoming it as much as finding ways to feel it when it comes, and it comes again and again. Not even Elizabeth Kubler Ross, with her five stages of grief, believed grief was a thing gotten over. It’s harmful to pressure people to speed up their grieving. I grew up by the ocean, so most of my life lessons can be explained in marine metaphors. A vibrant sea responds to currents, the moon’s gravity, everything around it.

To grieve is to stand in the surf. If you understand the ebb and flow of tides, of wave sets, you can move with it. You may even feel enlivened by the ride. But if you try to fight the sea, you’ll get knocked down, rolled around, and spit out onto the shore. It might even kill you.

The hardest drawings for me to make were the dark pages that follow Luna’s death. I had to stand in the saddest, heaviest surf I’ve ever known to make those drawings. I had to reach into my memories to recall how I felt after she died and draw those feelings. I had to use both hands. I’m not ambidextrous, but I can scribble with my left, so I recalled October 3, 1976, and scribbled my hurt and shame onto the paper. Just looking at these drawings conjures up this grief. I paired the dark pages with words mostly mined from my old journals. I needed their fragmented sorrow, how they were like scraps of a life fluttering about in the breeze as time passed.

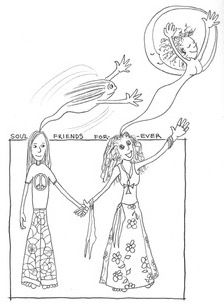

The other cartoons, comics, and illustrations have a different purpose. Luna’s death cast a deep shadow on my life and I show it that way, but throughout the story, I experienced a mixture of light and dark moments. Take, for example, when I was sexually abused by a drifter. Obviously, this was a shitty moment for me. Maybe it’s hard to understand, but I wanted to offer the cartoons as a kind of buoyancy compensator for the heaviness of this experience. And to reveal the truth, which was that he was a captivating grown-up and a monster at the same time. The drawings provide levity and contrast, and I hope they work together with the words to convey life as it was, mixed and magical, terrifying and splendid. I hope they reveal that my childhood was not all darkness. Part of it was a wonderful adventure, being Luna’s friend the biggest adventure of all.

The number one reason I created this book is that I believe people should be remembered for how they’ve lived their lives, not for how they left it. Luna’s death has overshadowed the magic of her life since 1976 and I’m so happy that I can now share what I knew of her as a living human being.

1970s Berkeley seems both ridiculous and horrifying in retrospect. As a parent and a person in sobriety, I couldn’t conjure a true sense of the times in my grown-up voice.

—Rebecca Fish Ewan

Ariel Gore: Your book is such a unique genre-bend of poetry, prose, and drawing. How did you get to that form?

Rebecca Fish Ewan: Arriving at the form was essential to uncovering the story. Form-wise, I had two distinct ah-ha moments—the first in 2013, watching my 12-year-old son curled up on the couch. My son, who is now a big gangling teen, looked so tiny at twelve, it struck me that this is what I must’ve looked like when the story of my friendship with Luna began. I understood in that moment that me-then had to be the narrator. Not adult-professor-mom me, but this child. I was a waif at 12 and stayed small until I started eating beef midway through high school. Waif-me needed to take readers by the hand and show them the story as it unfolded. The book’s quick unpunctuated free verse grew out of that recognition. It was the form her voice required.

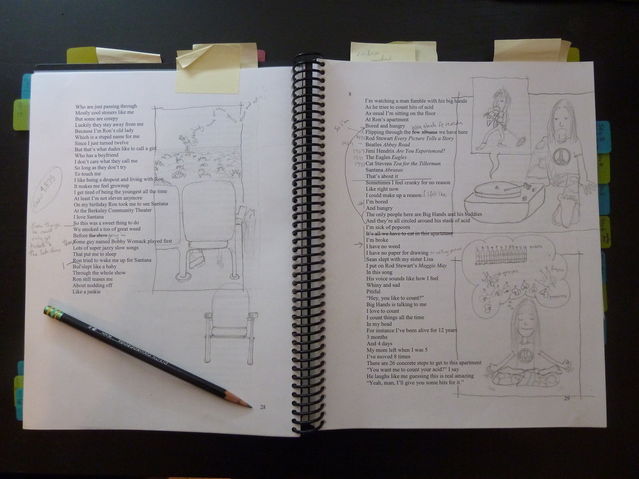

This discovery led to the second moment, months later when I sat hunkered at my desk, pencil in hand, struggling over edits for the draft poetry manuscript that the image of my son had unlocked. I started sketching on top of the words to help me see the scenes more clearly. At first, I drew to help me sculpt the text. The more I drew, the clearer it became that the drawings needed to be in the book. They were essential to the storytelling.

I entertained reworking the whole book into comic form, but that would’ve obliterated the voice I had found in the poetry. Instead, I set them side-by-side, cartoons on one page and free verse on the other, so they could bring the story to the reader together, as distinct yet connected forms that work together to create something new. Like harmony.

So, I had those two ah-ha moments and a form was born. Instant magic! Presto! Right? In truth, I toiled for years to arrive at those two sparks of insight. First, I tried writing this story as a straight memoir, using a reflective adult narrator who is remembering her childhood. This failed completely. 1970s Berkeley seems both ridiculous and horrifying in retrospect. As a parent and a person in sobriety, I couldn’t conjure a true sense of the times in my grown-up voice. The writing fell flat, weighed down by the wisdom of hindsight. So, I tried fictionalizing the story. I wrote a four-book series for young adults about following love into alternative universes by blood-fainting under the full moon. Fiction is not my wheelhouse, but I learned a ton about storytelling while writing the Love Lines series. I also blundered my way through dozens of mortifyingly bad query letters. I don’t believe in wasted time, so even though none of these novels have been published, they were essential to bringing By the Forces of Gravity to life. Mistakes are how I learn, so I had to make a lot of them to get to the form for this book. And all that bumbling around helped me wrestle the memories out of my mind’s dark recesses where I had squirreled them away.

The seventies, as an era, has a reputation for free love, which is often misinterpreted as informed love. Or fully self-aware and open love. But it was actually a very binary, homophobic and misogynistic time.

—Rebecca Fish Ewan

Ariel Gore: I love the way in the book that Luna comes in as the more-developed, sexually experienced child, and the way your waif-self looks up to her even as you struggle to protect your own sexuality from lecherous men. How do you see this friendship influencing your character’s development?

Rebecca Fish Ewan: I have always felt distinctly different from girls and women like Luna, those who I used to consider real girls versus my imposter self. The old term for girls like me was 'tomboy.' The thing about being a tomboy, is men still regard you as a girl. You have a vagina and they desire that, and if they feel you are vulnerable enough, they will grab it without asking for permission, without asking if you’re okay with it. This was happening to me before and as I was becoming friends with Luna. She embodied an intensely feminine energy. I was in awe of it. I was envious of it. And, I desired it for myself. The confusing part of being sexualized by others at a very young age—men and boys tried, as we called it then, to de-virginiatize me beginning when I was 12 years old—at the same time as I was forming a deep childhood friendship, is how love and sex get blurred.

I could write another memoir on where all that confusion left me as a young adult. For one, thinking every time I made a friend, I should show them how I care by jumping in the sack with them. Eventually, I learned that I don’t have to have sex with everyone I like. And I don’t have to love everyone who is physically attractive to me. In By the Forces of Gravity, because it is told from the perspective of my young self, I don’t have these kinds of adult revelations. I bumble through with what I know. I know I love Luna more than anyone. If she had said, hey let’s be girlfriend girlfriends, I would have done that for sure, even if my predilection has mostly been for males. But we were twelve, an age when girls have girl-bonds that transcend sexuality. The book is about our friendship and navigating it through a complex and at times abusive social environment. In the seventies, at least the seventies I experienced, children were sexualized and this made platonic friendships confusing.

In the seventies, there also wasn’t a common language for the diverse and fluid nature of human gender and sexuality that we know today. Nonbinary. Genderqueer. Gender Fluid. The list grows every day and thank goodness for that. The seventies, as an era, has a reputation for free love, which is often misinterpreted as informed love. Or fully self-aware and open love. But it was actually a very binary, homophobic, and misogynistic time. Even in Berkeley. For the most part, girls were thought of as male playthings. You were supposed to be flattered if a boy desired you. You were supposed to work at being attractive to boys, which meant being hyper-feminine. Feather your hair, wear hip-huggers, and make-up. Shit like that. Sex was a mechanism for keeping boys interested in you. All I had to prove my girlness was a vagina. The rest of me was pure tomboy.

Even though it’s true that my love for Luna was deep and confusing, I cherish it to this day. Hell, I wrote a book about it. The regret I have is not so much that I was a child and couldn’t figure out my feelings. My regret is that I squandered time I could have spent with Luna when she was alive by being jealous and angry about sharing her love with other people. Luna tried to teach me about the infinite nature of love. I get it now, but I didn’t then.

The laissez-faire parenting and educational system both empowered and endangered children. Before I dropped out of elementary school, I took a beer-making class. At a public school.

—Rebecca Fish Ewan

Ariel Gore: What aspects of hippie values and culture would you like to see a resurgence of? Which experiments of that time would you consider failures—or at least things not to try again?

Rebecca Fish Ewan: The laissez-faire parenting and educational system both empowered and endangered children. Before I dropped out of elementary school, I took a beer-making class. At a public school. Probably not an ideal subject for a budding alcoholic. My dad let me move into a commune just for kids when I was twelve. Maybe he could have been a little stricter as a parent. But his looseness and the social softness on truancy afforded me freedoms that taught me to be independent, to think for myself, to get by on next to nothing. In a world where people wouldn’t dream of harming children, letting them roam free can be healthy. I would like to see more faith put in children’s independence, but not to the same degree I experienced as a child.

A failed experiment was letting the whole free love thing apply to children. I’m sure I wasn’t the only kid in the seventies made to feel like an uptight square if I didn’t let some full-grown adult grope me. I was sexually abused under the guise of sexual freedom. It was wrong then. It’d be wrong now.

What I long for from the seventies, beyond a resurgence of awesome music, is actually one of its myths. Berkeley in the seventies is believed to be all peace, love, and oneness. The world could use more of this right now, but the truth is misogyny, homophobia, and other forms of human cruelty and intolerance were very much alive in the seventies. Prior to the current administration, I felt like true progress was being made to eradicate hatred towards women, people in the LGBTQ community, people of color, people living in poverty, people with mental and physical challenges, and all the myriad ways people are othered, oppressed and discriminated against. I get it now that I underestimated the human capacity for hatred.

A lot of people gripe about millennials, but I’m encouraged by today’s young people. I recognize their youthful sense of urgency about climate change, ecological degradation, hunger, violence, racism, bigotry, misogyny. I see in them a resurgence of the peace, love, and oneness of the seventies. Only this time, it feels more urgent and necessary. I feel like they’re more protective of their identities, rights, bodies, and dignity. This gives me hope.