Spirituality

Positioning Our Knowledge in Four Quadrants

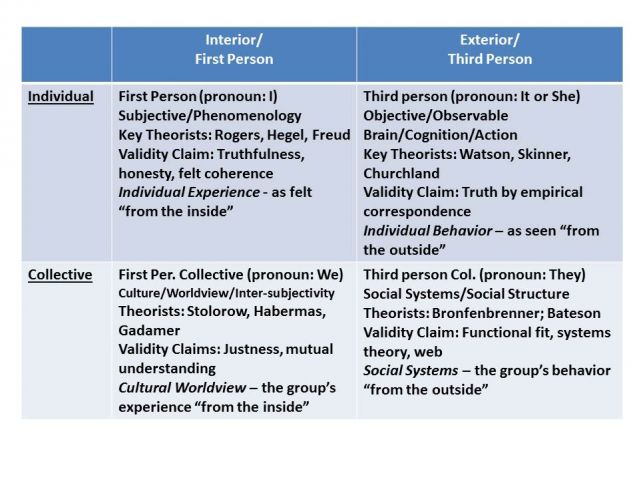

Four quadrants that help make sense out of different philosophies.

Posted October 14, 2015 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Written with Professor Andre Marquis, University of Rochester

One of the basic claims that stems from the unified approach is that human knowledge is “positional,” meaning that human knowers exist at certain points in social and historical contexts and that their position in these contexts frames what it is that they claim to be justified (see here for an example of this perspective applied to the therapeutic context).

This post introduces a complementary view on understanding how knowledge is inevitably positional, derived from the work of Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory. Integral theory is a broad, rich, and complex system that, not unlike the unified approach, attempts to provide the outline of a Theory of Everything. It is simultaneously philosophical, psychological, and spiritual, and in our opinion warrants serious consideration from any scholar who is attempting to develop broad philosophical or meta-theoretical systems. The whole of integral theory is too complex to be effectively summarized here, and readers are referred to Wilber’s work here for summaries of the philosophy, and here for Andre Marquis’ work that summarizes how integral theory applies to psychotherapy and psychopathology.

One of the most useful aspects of Wilber’s theory is the frame it provides for epistemology and especially for understanding why there are different epistemologies and why they conflict. Epistemology refers to how people know things and what kind of knowledge is valid.

To make sense out of the cacophony of different perspectives on epistemology, Wilber offers a four-quadrant model, framed by two axes. The first axis is the interior-exterior axis, and it refers to whether one is considering knowledge from a first-person perspective (i.e., interior) or whether one is considering knowledge from a third-person, objective perspective (i.e., exterior). The second axis is whether one is focused at the level of the individual or at the level of the collective. The combination of the two axes gives rise to the four quadrants: interior-individual; exterior-individual; interior-collective; and exterior-collective. The key elements of the four quadrants are captured in this table and described in more detail below.

The interior-individual view is concerned with phenomenology, which refers to the first-person experience of being. When you open your eyes in the morning, your “theater of consciousness” comes online. You see the world full of shapes and colors and perceive meaning all around you. The philosopher Hegel began with this view and developed a philosophy from this starting point. Solipsism is the term for the belief that the only “true” entity is one’s own mind and would represent a radical or extreme commitment to this quadrant.

The exterior-individual view is concerned with behavior; that is, that which is observable from the third-person perspective or that which can be measured or captured by a video. When behaviorists like John Watson objected to early studies on consciousness and argued that the true natural sciences did not allow for such concepts like consciousness, they were arguing strongly for an exterior-individual view. Indeed, Watson’s behaviorism is a form of radical exterior-individual epistemology. It is important to note here that a brain-based view would also fall into this quadrant, as well as perspectives in computational neuroscience. They all take an objective, third-person view in their attempts to explain behavior.

The interior-collective view is concerned with the relational and socio-cultural construction of reality. The perspective here is that we are inherently relational beings and relational knowers and our knowledge systems are inextricably tied to that social context. Hermeneutics, feminist perspectives, and strong cultural psychology perspectives tend to operate from the interior-collective view. The radical interior-collective view is that all knowledge is inherently socially constructed and there is no truth independent of the social, historical, and cultural context. An extreme example of this view is when Sandra Harding referred to Newton's Principia Mathematica as a "rape manual" in her 1986 book, The Science Question in Feminism because it supposedly embodied the dominant patriarchy of the time.

The exterior-collective view is concerned with social systems and how social systems operate from the third-person perspective. Individuals like the sociologist Emile Durkheim exemplified this view, for example, by explaining suicidal behavior in terms of degrees of social interconnectedness. Macro-economists and sociologists often emphasize this perspective. Donald Black’s pure sociology, which argues that to explain social behavior, one needs to consider only the geometry of social relations across time and distance and nothing else (i.e., psychology is completely irrelevant) is an example of a radical exterior-collective view.

Integral theory claims that the knowledge perspectives represented by these quadrants are (a) dynamically interrelated (events or aspects of one quadrant influence goings-on in the other quadrants); (b) complementary (the same event or slice of reality can be, potentially, fruitfully considered from multiple quadrants); and (c) irreducible (one will never obtain a full description of one quadrant by relying completely on the other quadrants, thus all the quadrants are necessary for a full understanding of human behavior and human knowing).

The quadrants from integral theory provide a very useful meta-perspective that enables one to grasp why different philosophical or scientific paradigms (e.g., phenomenology versus behaviorism) that initially appear to be fundamentally incompatible can potentially be understood in much more complementary ways. In addition, the quadrants enable us to maintain clarity about the kinds of evidence that can be used to support particular kinds of claims. For example, subjective, phenomenological “evidence” (i.e., intuitively feeling or experiencing truths) should not be used to confirm behavioral truths (objective or third-person descriptions of cause and effect).

Interestingly, even some who work from an integral perspective have found themselves confused on this point. The next post (Part II), by Andre Marquis, weighs in on some debates about spirituality that have been occurring in the integral community and uses the quadrants to remind folks that phenomenological evidence of a higher power found via spiritual transcendence (events in the interior-individual quadrant) should not be confused with evidence of such entities in the natural or behavioral scientific sense of the term (the exterior-individual perspective).

This is an important debate to share with a broader audience outside the integral community for at least two reasons. First, too many in our culture, especially in religious contexts, move from the claim that “I (or we) feel and believe in God strongly” (the interior quadrants) to the claim that now we can pressure our government or others to act as if this were a given, independent truth about the world (the exterior quadrants). On the flip side, many scientific atheists are so strong in their commitment to a third-person knowing that they dismissively reject spirituality and other notions in a way that is fallacious. The quadrants help to make sense out of how to hold these various claims without either dismissing phenomenology or making irrational truth claims in problematic ways. (See this post on building understanding between spiritual/religious and scientific worldviews.)