Stress

Why Stress Is Both Good and Bad

Five facts that might surprise you—plus advice on how to cope.

Posted January 20, 2016 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Stress. We use that word quite a bit. And for good reason.

The American Psychological Association’s Stress in America survey discovered that recent stress levels in the U.S. population are 4.9 on a 10-point scale, with 10 being the highest level of stress. The most common stress sources are money, work, the economy, family responsibilities, and health concerns.

But what exactly is stress? Why do we experience it?

Here are five interesting facts about stress that might surprise you.

1. Stress is good

Stress is actually useful. Without stress, we would not be here to talk about stress. If our hunter-gatherer ancestors did not experience some stress when that lion was roaming around their sleeping quarters, or when those red berries looked good but also emitted a strange odor, they would have been eaten or poisoned. Hence, our ancestors experienced stress and used it to their advantage so that they could procreate, allowing us to have this discussion today.

Even in modern society, stress is useful. If college students didn't experience any stress over tests, they probably wouldn't study or show up for class. If workers didn't experience stress about project deadlines, they might end up getting fired.

So, stress keeps us accountable for our actions. It motivates us and inspires us to be better citizens.

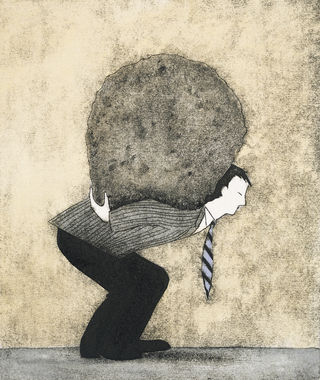

2. Stress is bad

Unfortunately, there are equally as many reasons why stress is bad. Whereas mild stressors—such as what to get your spouse for his or her birthday—are motivating, major stressors can be debilitating. For instance, caring for a loved one who has a chronic illness is a serious stressor. Chronic or major stressors are extremely taxing on the brain and the body, possibly leading to depression and other mental health consequences, as well as physical health issues.

3. Stress is contagious

Stress is intimately tied to our social world. Social stress, such as feelings of loneliness or isolation, takes a toll on the brain and body. These forms of stress can lead to depression, anxiety, and heart disease.

But stress does not have to affect us directly to change our brains. Stress can also be contagious. Many of the sources of stress in our daily lives may not be ours directly, but rather those of our loved ones, such as health problems affecting a loved one, family responsibilities, and relationship issues. These stressors also have mental and physical health consequences—for our loved ones and for us.

4. We can learn about stress from animals

Animals can teach us quite a bit about stress. For example, prairie voles are social rodents. Scientists use them to study how the social environment influences health, and how we can cope with stress. Like people, prairie voles live in family groups, raise offspring cooperatively (both parents together), and display many negative effects from changes in their social environment.

We have learned from these rodents that social stress can influence the way that the brain communicates with the body and lead to poor functioning of the heart, increasing the risk for heart disease. We also have learned that exercise can be a useful strategy for reducing the effects of social stress. In fact, my laboratory is currently using these rodents to understand how the brain changes in response to contagious stress (stay tuned for results in a future blog).

5. Stress is about perception

So this brings us back to the original question. What exactly is stress?

Stress is a perceived disconnect between a situation and our resources to deal with the situation. In other words, stress is a (real or imagined) threat that taxes our resources. The operative word here is perceived. Stress does not always arise from an actual threat; but if we perceive it to be a threat, then it's a threat.

Consider a ride on a roller coaster, for example. For one person, this is a fun and fantastic thrill. For another person, it’s a scary and stress-inducing event.

If we perceive something as stressful, our brains release hormones into the blood. These hormones change our behavior, mental experience, and physical functioning. If the threat is real, such as a lion that is about to eat us, these hormones will help save our lives, for instance by helping to deliver necessary oxygen to our legs so we can run.

If the threat is imagined, such as thinking about a potential traffic jam each morning that will make us late for work, these same hormones flow through our bloodstreams. Over time, these hormones use critical energy, causing a detriment to our body and leading to psychological and physical problems.

So what can we do to combat bad stress?

The fact that stress is a perception also means that we can do something about it. We can train ourselves (or we can be trained by a professional, if necessary) to change our perspective.

Remember that stress is a perceived disconnect between the situation and our resources to handle the situation. Therefore, there are two possible ways we can change our perspective about stress.

First, we might be able to change the situation. If traffic is a chronic source of stress, can we take the train to work?

Second, in situations that cannot be changed directly, we can possibly change the way we view the situation. If we have no other option but to drive to work, can we use that time to our advantage instead of dwelling on how slowly the traffic is moving?

Perhaps we can use the time to mentally plan the day, so that when we arrive to work we are ready to get started. Perhaps we can use the time to relax and listen to some music or an audiobook. Perhaps we can engage in some mild relaxation exercises before we leave the house, so that when we get in the car we are equipped to cope with the traffic.

Some stress might be inevitable. But its negative effects on the brain and body do not have to be inevitable.

By altering the way we interpret the world around us, we can gain control over stress. By changing our perception about a situation, we can even gain the power to see its benefits.

Angela Grippo is an associate professor of psychology at Northern Illinois University.

References

American Psychological Association (2014). Stress in America. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/.

Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT (2015). Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 238-249.

Grippo AJ (2011). The utility of animal models in understanding links between psychosocial processes and cardiovascular health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5/4: 164-179.

Sgoifo A, Carnevali L, Grippo AJ (2014). The socially stressed heart: insights from studies in rodents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 39C: 50-60.

Wardwell J, McNeal N, Scotti ML, Colburn W, Dotson A, Ihm E, Woodbury M, Grippo AJ (2015). Combined vicarious stress and social buffering in the prairie vole. Society for Neuroscience (Chicago, IL).

Sapolsky RM (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers. Henry Holt and Company, New York, NY.