Fear

Tachysensia: One Small Survey Tells a Lot

A small sample of stories about a fast-feeling syndrome.

Posted October 11, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

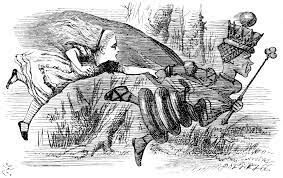

- Tachysensia/Alice-in-Wonderland syndrome may be a form of migraine.

- Symptoms can be frightening, but they shouldn’t be.

- Through submitted stories we have a representative picture of how it feels to be in an episode of tachysensia.

A year has passed since my latest piece about tachysensia with Dr. Osman Farooq, clinical associate professor of neurology at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Buffalo. In earlier posts, long before I had any backup information from neurologists, I wrote, “with billions of neuronal connections firing 24 hours a day, an occasional short-circuited moment is likely to happen when the brain memory of its developmental experiences of circadian time misfires because of a blip of electro- or biochemical interference. Those occasional interferences often accommodate strange mind-changing inhibitors producing fear, awe, stress, and changes in body temperature.”

At the time, It was a risky thing to say, for I am a science journalist, not a neurologist. Now, since reading more than a hundred replies to my last post, and consultations with Dr. Farooq, I believe that I was correct in everything posted so far, including the point that tachysensia/Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS) is another form of migraine.

The brain follows a complex synchronization between what it expects of the world and what the body needs to stay alive and healthy. So, with the billions of neurons that could misfire electrical signals, there are bound to be rare moments of speed-sense confusion that have us perceive speeds and sizes volumes that do not align with familiarity. It is rather astounding that bouts of tachysensia do not occasionally hit every human on the planet. Yet, perhaps they do and we just don't hear about it.

Limited Information From the Survey

We now have some tentative results from the survey that was distributed back in December 2020. From the data, which admittedly are not large enough to secure high degrees of sureness, we can speculate that the norm of durations is between 5 and 10 minutes and that the frequencies of episodes scatter between 2 and 12 per year. There are occasional long durations and high frequencies. For cases with durations less than 20 minutes and frequencies less than 15 per year, there should be comfort in having that lucky fast-forward feeling symptom of migraine rather than having knife-edge pain typically associated with migraines.

Experiences of loud and aggressive sounds are prevalent but inarticulate and without instructions for behavior. There were few reports of headaches and none with epileptic seizures. The average age of the first occurrence is not calculable because many responders did not answer that question. However, I guess it begins at puberty, and, for most people, the frequency diminishes significantly with age.

There were many replies from young people, mostly teenagers, who were frightened, believing that something was wrong with their eyes or brains. Many said they had not told their parents and had not seen a doctor. For those cases, all within the norms, I was able to reassure readers that their episodes are not to be feared but that they should let their parents know or make an appointment to see a doctor. The first few episodes tend to be frightening but, after a while, when they end quickly and do not happen often, fear recedes. With age comes a calming as frequencies diminish. Many adults have moderate fears, and some have learned to enjoy their episodes.

The Representative Picture

So many people wrote descriptions that read as if they were dream experiences rather than episodes in living awareness. I included three of those dream-like narratives in a previous posting, “Uncovering the Mystery of Tachysensia.” And, now, out of a hundred of the most recent replies to the survey, I pick one (translated from French with permission) that presents a collage of the most vivid representative accounts of how episodes feel to the person experiencing an attack:

Everything is normal, and then, suddenly, I feel that my brain "disconnects" from reality. It is as if I no longer live "with the times" of others. Sounds come to me much louder than normal. But I know that it's my brain that perceives them too strongly because they are aggressive and poorly ranked among them. A bit as if it took all the information from my environment without sorting out the useful information.

The gestures and movements around me accelerate as if someone had put "fast forward" on the film of life. I perceive all the movements everywhere around at the same time, they are aggressive and too fast. But I can receive sounds at normal speed, while I see gestures in fast-forward. Which is kind of a mathematical impossibility when you think about it. Yet it is possible to receive it neurologically as well!

This is also reflected in the music I listen to. I hear a piece of music that I know, but it sounds different. The tracks seem to shift as if my brain heard them separately but no longer knew how to put them together. I have trouble following as if each piece of information is received in one part of my head and reassembled incorrectly. Rhythm is lost. The bass seems super-strong, and the song is totally distorted compared to what I once knew so well.

It was a typical picture, although more detailed than most. More data come in by the day with similar narratives, though some messages of concern tell of debilitating, high-frequency episodes lasting more than 20 minutes. For those rare cases, I would recommend professional consultation.

No one should be frightened by a few episodes per year that last under 20 minutes. They are likely to be the symptoms of migraines without headaches. If there is a concern, however, it would be best to see a neurologist. For most people, the outcome is often favorable.

With so many cases of a condition (very likely many millions) that we now call tachysensia, it seems astonishing that the medical community continues to be relatively unaware of the syndrome. Fortunately, for cases involving infrequent and short durations, tachysensia is nothing to fear. With more research, we should have more definite answers. That will come soon.

References

Saskia de Leede-Smith and Emma Barkus, “A Comprehensive review of auditory verbal hallucinations: Lifetime prevalence, correlates and mechanisms in healthy and clinical individuals,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience,” 7 (2013): 367.

Osman Farooq MD, Edward J. Fine MD, “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Historical and Medical Review,” Pediatric Neurology, 77 (2017) 5-11.

Joseph Dooley, Kevin Gordon and Peter Camfield “The Rushes: A Migrain Variant With Hallucinations of Time,” Clinical Pediatrics (Sept. 1, 1990) Vol. 29 No. 9 536-538.