Bias

What Is Your COVID-19 Story?

Many believe this pandemic will be a defining moment. How will you be defined?

Posted April 14, 2020

Many say COVID-19 may very well be the defining moment of a generation. We cannot escape news stories, daily and weekly statistical updates, and forecasts for the future. For some, the path is one of a hero. For others, an opportunity. For still others, a tragedy. The goal of this post is to get the reader to think about what she wants her story to be and to create that story by overcoming some of the cognitive biases that may be controlling behavior.

In the weeks that this virus has dominated public discourse, I have listened to around a dozen podcasts that have a theme related to the coronavirus. All have been podcasts I listen to regularly, and most are psychological in nature. The one that made me decide to write about this focused over half of the hour-plus podcast on how the human brain worked against preventing the pandemic. It focused on cognitive distortions that occur naturally and lead one to view the virus, and information about the virus, (as well as other aspects of reality) in a distorted fashion.

David McRaney interviews several experts for his podcast “You’re Not So Smart” to answer the question, “why didn’t people stay at home?” The discussion starts with a common cognitive bias, “Fundamental Attribution Error,” which I’ve discussed at length in other posts. This is when one attributes others' behavior to their character, but when one does something “wrong” it is attributed to the situation.

The most relevant example of this with COVID-19 is looking at those that didn’t follow suggestions to stay home, etc. right away as dumb or evil. As I wrote in “Politics and Self-Actualization,” when someone is viewed in conflict with what one considers a correct belief, there are three phases we go through: The first is believing he just does not have the correct information. When the correct information is evident and her view hasn’t changed, she is viewed as stupid. When it is realized the person is not stupid, the third phase is he must be evil. This is a reflection of fundamental attribution error. When “we” do the wrong thing, it is circumstances. When “they” do the wrong thing, it is their character, who they are.

The experts go on to discuss the following cognitive distortions and biases that contributed to people’s behavior with COVID-19:

- Complexity: Dr. Julia Shaw explains, “We’re really bad at understanding things that are big, global and have long-term implications” (McRaney) as our minds are designed to be more tribal. Then Dr. Joe Hanson explains that with viruses of this nature, you’re always playing catchup and always one to two weeks behind. He provides a great analogy of a pond that starts with one lily pad, but the lily pads double daily until it’s completely covered in 60 days. He discusses how when asked, “when will the pond be half full of lily pads?” people intuitively respond around 30 days. However, this is actually very wrong. The pond will be half full of lily pads at 59 days. He goes on to point out how when asked the more difficult question, “when will 1% of the pond be covered?” many can’t imagine it is on day 54. So it is with this virus. It grows exponentially, but in the beginning, it seems so slow no one worries about it.

- Learned Helplessness: When no matter what you seem to do, nothing works, you may then decide to do nothing. Learned helplessness was demonstrated in animals. When one side of their cage was electrified they’d jump to the other side. Eventually, when both sides were electrified, they would lay there and be shocked. Learned helplessness is a theory for depression and posits that when nothing is working, a person stops doing anything that might work. In the case of COVID-19, conflicting reports from officials and rapidly changing guidelines may have made some feel like no one knows what to do, nothing can be done, so why should I do anything.

- Wishful Thinking: When nothing seems to work and it seems overwhelming, people look for evidence to support what they want to be true. Confirmation bias, where we find evidence for what we already believe, plays a part in this. In the case of COVID-19, you can find that it is one or another conspiracy, and when you combine this with its slow growth, people may find evidence this is just another sensationalized story.

- Normalcy Bias: This is the expectation that things will go on as they have. Of course, there is a lot of evidence to support this: The sun comes up every day. Most of us (before the pandemic) did the same things every day. We expect the next day to be much like the last. In the case of COVID-19 and any other emergency, this bias works against acting quickly. It is so common first responders call it negative panic. McRaney quotes psychologist John Leach who posits about 75% of people will wait and see what to do rather than act right away. Part of this is normalcy bias.

- Social Contagion: This is the idea that people mimic or copy the behavior of others. In regard to COVID-19, seeing others out may influence others to go out. McRaney makes the case that there is evidence in studies that COVID-19 behavior is similar along partisan lines.

Above are the ways your behavior may have been influenced by common psychological phenomenon. Everyone would like to believe they are above such mind tricks, but the truth is no one is. I can certainly relate to some of these and see how my behavior was affected in the early days of COVID-19 in the U.S. The question becomes, what will you do about it?

I have written a great deal about cognitive distortions and what that has to do with personal narratives. In short, humans create stories about the events in their lives that suit their needs. Perception is not reality; everyone’s perception is filtered through their history, their own truth, which is distorted because of biases.

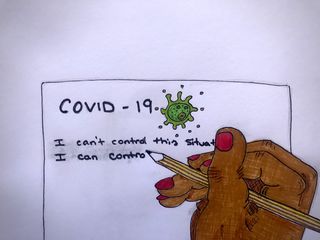

In that writing, I encourage readers to be aware of their mind's tendency to distort reality to fit their needs. I encourage the questioning of thinking, a more conscious approach to living, and the ability to create, or recreate oneself. This is an opportunity to do that. This pandemic is an opportunity to recognize one’s distortions, and to choose a different path, to choose who one will be, and what their story about this pandemic will be. There are innumerable story templates to choose from, from unseen heroes, to frontline heroes, to opportunist, to self-improvement, to almost anything you choose to make it. There will inevitably be sorrow. Lives will end and others will be forever changed. Hardships will be faced and, hopefully, overcome. Some of the story is the environment, everything outside of you. But some, and the only part you can control, is how you behave, who you choose to be, and inevitably, what your story will be about this pandemic.

One may focus on overcoming the hardship, and how that shaped him. One might tell the story of how it affected her relationship, strengthening it, or destroying it. Some will be changed forever as a result of the changes they decide to make, the reevaluation of their values, and the subsequent change in behavior. Some might discuss how the pandemic made them want to live life more fully and chase things they feared chasing previously. Some, unfortunately, will return to a life they have always complained about and leave any thoughts of change behind. Which will you be? What will your story about this pandemic be?

Copyright William Berry 2020

References

McRaney, D., (2020, April 5) 177-COVID-19 [Audio Podcast] https://soundcloud.com/youarenotsosmart/177-covid-19

Schulz, K; 2011; On Being Wrong; TED Talk; Retrieved from: http://www.ted.com/talks/kathryn_schulz_on_being_wrong on 11/20/16