Psychology

Two Ways Marketers Realize Stealthy Price Increases

They minimize coupons and sales and add higher-priced, higher-value offerings.

Posted January 4, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

"Overall Promotional Intensity in both the multi-outlet and grocery channels has been consistently below last year's levels at the total CPG, total edible, total non-edible, and category levels." – Finding from IRI CPG Promotional Index.

This past fall, I came across a rather strange headline on CNBC: "Peloton cuts prices, capitalizing on people staying at home." Peloton is the maker of expensive stationary bicycles and treadmills and one of the success stories of the Covid-19 pandemic. The company's stock price was around $28 in February 2020, and today (early January 2021), it is over $151. It benefited because millions of Americans canceled their gym memberships and started working out at home. The demand for stationary bikes and treadmills went through the roof. Why, then, would Peloton cut prices instead of increasing them?

This question lies at the center of an interesting consumer psychology conundrum faced by marketers of suddenly popular products. Imagine that you work for a company that makes and markets a product that everyone wants, courtesy of the pandemic, say Clorox wipes or HelloFresh meal kits, or Peloton bikes. While the higher demand is good news, it also creates a fascinating and difficult pricing challenge involving two conflicting goals.

On the one hand, you want to benefit from your products' popularity and make a higher profit. After all, what better time to raise prices and earn a higher profit margin than when everyone wants your products? On the other hand, simply raising the price of your products won't work. Your customers will feel betrayed and think you are taking advantage of them. They may even accuse you of price gouging. The negative publicity from raising prices will damage your brand's reputation and hurt the company in the long run. What to do?

To answer this question, it is essential to understand the psychology behind how consumers use price information in their buying decisions. Smart marketers rarely raise the list or regular prices of their products. Instead, they use more nuanced pricing strategies that achieve the same result of effectively increasing the price paid by customers. I know this sounds impossible. How can a seller increase their prices without raising their regular prices? In this post, I want to explain two methods that marketers, of suddenly popular products, use to do this. (There are other methods, but let's focus on these two).

Method 1: Reduce or stop offering coupons and sales to customers.

Price promotions are commonly used to market consumer products. They are particularly significant for packaged goods (or what marketers call Fast Moving Consumer Goods or FMCG) that we buy in grocery stores. If they are chasing a deal, consumers only have to wait, and the detergent, the frozen pizza, the soda, and most other groceries they buy will be available for a lower promotional price. The offer could take any number of forms such as a sale, a manufacturer's coupon to be clipped for 50 cents off, 75 cents off, a buy one get one half off, and so on.

Although consumers don't think of it this way, price promotions work as a stealthy and highly controlled price change. Promotions are particularly useful to the seller to implement temporary price increases. To see why, imagine a cleaning products company that sells a gallon of bleach at a regular price of $5. It also runs different price promotions throughout the year like coupons, BOGO, limited-time sales, etc. so that customers effectively only pay an average price of $4 per gallon after the promotions are accounted for.

Now imagine that bleach becomes very popular and everyone is using more of it to clean and disinfect their homes and workplaces. The bleach company can increase its price by merely reducing or eliminating its price promotions. While the demand remains elevated, no more coupons, no more sales, no more offers of Buy One Get One! The result will be that all bleach-buyers will have to pay the regular $5 price. With this move, the company has essentially increased the bleach's price by 25 percent, from $4 to $5, by eliminating price promotions. All the while, the regular price of the bleach has remained unchanged, so customers can't really complain.

We can see this principle at work in the explanation provided by Clorox's CEO Linda Rendle, for the strong financial performance of her company's brands, in a recent earnings call to Wall Street analysts:

"So those two things coming together, a revival of our business plans, having the right merchandising plans in place, and you know, there was very little price discounting during this entire period of COVID, and we still saw the volumes hold steady and the sales increase that we experienced."

Method 2: Use a Good-Better-Best pricing strategy

A second method to "increase the price paid by customers without raising regular prices" is introducing new and better quality versions of the product at higher prices while maintaining the price of the existing product. This is called a "good-better-best" (GBB) pricing strategy. From the consumer's perspective, GBB pricing looks good for their welfare because it gives them more options to choose from. And this is indeed the case. However, a common side-effect of GBB pricing is to function as a stealthy price increase.

Let's return to the cleaning products company selling a gallon of bleach for $5. To use the GBB pricing method, let's imagine it introduces two new bleach products, a new bleach that is viscous and doesn't splash ("no-splash") and a bleach that has a lavender scent. Because both products have extra features, the company charges $7 a piece for them instead of $5. Introducing these new products also acts as an effective price increase. This is because even though the company maintained the regular bleach's price at $5, its customers are now paying a higher average price: many are buying the $7 bleach versions instead of the $5 basic bleach.

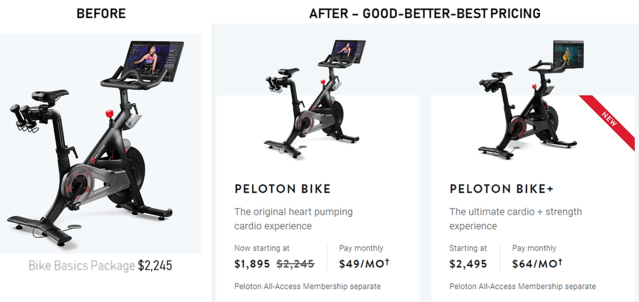

During the pandemic, many companies followed the GBB approach to take advantage of higher consumer demand and earn higher prices. As I pointed out earlier, instead of raising prices, Peloton lowered the price of its most popular basic spin bike by $350, or about 16 percent, from $2,245 to $1,895. At the same time, it introduced a more expensive new bike for $2,495, which is more profitable.

GBB pricing does two useful things for Peloton. First, the average price paid by Peloton-buyers increases. And second, the company sells $39 monthly memberships for virtual fitness classes to every bike owner. Higher bike sales (achieved by lowering the basic version's price) increase the customer base and the company's monthly revenue from memberships.

Similarly, Clorox introduced many "best" quality products throughout the year, such as compostable cleaning wipes, fabric sanitizers, and compostable trash bags. By and large, these are higher in quality (and in price) than the respective basic versions, resulting in an increase in the average prices paid by its customers.

The bottom line for consumers

Marketers don't have to splashily raise their products' regular prices to take advantage of higher consumer demand. In fact, doing so will be likely to cause more harm than good. What smart marketers do instead is to employ nuanced pricing strategies to reach the same goal. They increase prices stealthily without changing the regular prices of existing products. I must point out that the seller is not taking advantage of consumers with either method I've discussed here. What they are doing is aligning the customers' (higher) valuation of the newly popular product with new products and pricing offers.