Friends

Books as Friends

Books offer relationships not just with others but with ourselves

Posted May 29, 2012

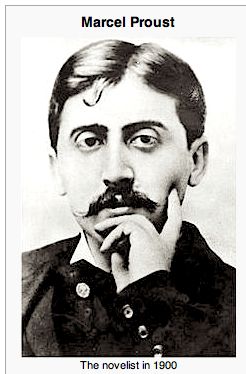

Proust at the time when he was immersed in Ruskin

However intimate our friendships, however much we value them, circumstance will have restricted our choice of people we can know. Books are friends we can choose without restriction.

This thought about the nature of friendship, and about our relationship with books, comes from John Ruskin, an English art critic of the nineteenth century. Although he's not much read now, in his time he was enormously influential. He made painters such as J. M. W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites popular, he engaged people's interest in architecture, he championed education for working people, and he denounced greed as the main motivation of British life.

A principal link from Ruskin to the psychology of fiction is via Marcel Proust who began to read Ruskin in 1897. During the next ten years he immersed himself in Ruskin, translated some of Ruskin's books into French, and published these translations. Proust's English wasn't good. He said he didn't claim to know English but that, instead, he claimed to know Ruskin. Proust went on to write his own essay, "On reading," which develops Ruskin's idea of books as friends. A new translation of this essay has recently been published by Hesperus. Proust's engagement with the mind of Ruskin was an important preparation for his great novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, for which he began to make notes in 1908.

Several people were responsible for inaugurating the era of modernism in fiction, which gave us a new kind of entry into the inwardness of mental life. Among them were James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. But none was more important than Marcel Proust, who developed the idea of a novel that was not just a friend, but a friend who enables us to become intimate both with other minds and with our own.

Here, for instance, is is a quotation from Le temps retrouvé, the final book of À la recherche du temps perdu (my translation, p. 424):

… it would even be inexact to say that I thought of those who read it as readers of my book. Because they were not, as I saw it, my readers. More exactly they were readers of themselves, my book being a sort of magnifying glass … by which I could give them the means to read within themselves.

Marcel Proust (1927/1987) Le temps retrouvé, Paris: Gallimard.

Marcel Proust (2011). Proust on reading, with Sesame and lilies 1: Of kings' treasuries by John Ruskin (D. Searls, Trans.). London: Hesperus.