Politics

A Brief History of Taking Down Competitors

Tall Poppy syndrome in antiquity.

Updated May 28, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- The thought that insubordinate subjects should be eliminated is older than history.

- It goes back to Herodotus, Aristotle and Livy.

- Julius Caesar failed to take their advice, and paid for it. His son learned from his mistakes.

- Alpha chimps take beta chimps out, anticipating Herodotus.

It’s lonely at the top.

There are reasons for that.

Long ago and far away, in the middle of the 5th-century BC, in a city on the Aegean in what has become Turkey, Herodotus told a story in his Histories. He wrote about Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus, who took an ambassador from Corinth on a walk through the country. His conversation was meaningless, but his actions were not. “He kept cutting off all the tallest ears of wheat which he could see, and throwing them away, until the finest and best grown part of the crop was ruined.” To the tyrant in Corinth, it was obvious what Thrasybulus was up to. “He recommended the murder of all the people in the city who were outstanding in influence or ability.”

A century later, Aristotle, who quoted Herodotus, got the point. In his Politics, he wrote: “Tyrants have borrowed the art of making war upon the notables and destroying them secretly or openly, or of exiling them because they are rivals and stand in the way of their power.” In short: “The prominent citizens must always be made away with.”

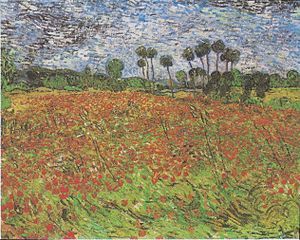

Three centuries later, Livy, who taught the Roman emperor Claudius, and probably had read Aristotle or Herodotus, rehashed that advice. In Ab Urbe Condidta, his history “From the Founding of the City,” he had Tarquin, the last of the Roman kings, respond to another ambassador from Gabii, who wanted to know how to secure power. “He said not a word in reply to his question, but with a thoughtful air went out into his garden. The man followed him, and Tarquin, strolling up and down in silence, began knocking off poppy heads with his stick.” Good advice, thought the ambassador’s boss. “Many were openly put to death; some, against whom any charge would be inconvenient to attempt to prove, were secretly assassinated. A few were allowed, or forced, to leave the country.”

The Betrayal of Caesar

Julius Caesar had invaded Britain and conquered a big part of what has become France, then won battles in Egypt, Northern Africa and Spain, when his senators put an end to him. After his civil wars were over, Caesar had famously spared his worst enemies. “This is a new way of conquering,” he wrote in a letter to Cicero, “to make clemency and generosity our shield.” Some opponents were promoted to high offices; others were given whole armies to command. Caesar was particularly happy to let Brutus live. He’d had affairs with his sister, and with his mother. So he set him up as a consul, the highest office under the republic; and as he was being stabbed in the groin, may or may not have complained: “You too, my son?”

Caesar’s successor learned from his father’s errors. Augustus used the law of treason to get rid of anybody who offended his maiestas, or majesty. Shortly after he became an emperor, he went after his prefect of Egypt, Cornelius “the Cock” Gallus, for insolence: “He not only set up images of himself practically everywhere in Egypt, but also inscribed upon the pyramids a list of his achievements.”

Gallus was prevented from living in the emperor's provinces, and eventually took his own life. A couple of years later, the immoderate and unrestrained Lucius Murena and a few friends were caught in a conspiracy to assassinate the emperor. “Seized by state authority, they suffered by law what they had wished to accomplish by violence.” Then Egnatius Rufus, a candidate for office who resembled a gladiator more than a senator, but won over too many voters, offended Augustus. Rufus and was executed, along with his followers. “Winds fell tall pines; lightning strikes at the high peaks.”

Parallels in Chimp Society

Pan troglodytes, commonly known as chimpanzees, generally restore order in similar ways. Frans de Waal, the prolific primatologist, started his career with a project in the Arnhem Zoo. He documented the antics of three males jockeying for power. Yeroen, calculating and ambitious, was the oldest; Luit was more vigorous, and more social; Nikkie, the youngest, was acrobatic and disruptive. Like a heavy steam engine or an attacking rhinoceros, Yeroen would charge at insubordinate group members, hair on end. After which his subordinates would greet him with low grunts, and grovel in front of him. But Yeroen was passing his peak.

One late summer night those apes got into in a fight. Nikkie was unhurt; Yeroen was scratched and cut. But Luit, who had challenged Yeroen for alpha status, and taken advantage of females in estrous, was covered with gashes on his head, flanks, back and around his anus. Several fingernails and toes were lost. There were a number of small, canine incisions in his scrotum. And his testicles had dropped out.

One is a dangerous number. Alpha is a risky letter.

In Memoriam:

References

Betzig, Laura. 2015. Suffodit inguina: Genital attacks on Roman emperors and other primates. Politics and the Life Sciences, 33: 54-68.

Betzig, Laura. 2021. A note on religion. In L. Betzig, ed., Human History as Natural History, in Evolutionary Psychology, 19, issue 4.

Waal, Frans de. 1982. Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes. New York: Harper & Row.

Waal, Frans de. 1986. The brutal elimination of a rival among captive male chimpanzees. Ethology and Sociobiology, 7: 237-251.