By most standards, Julius Caesar wasn’t attractive. He balded early (and was famous for combovers), but had hair all over his body (“Caesar” means hairy: he looked like an ape).

Women were all over him, anyway. Caesar slept with the wives of his enemies. There was Eunoë, who was married to the king of Mauretania; there was Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, who was married to her brother but gave birth to her Latin lover's bastard son. And Caesar slept with the wives of his friends. There was Pompey’s wife, Mucia—who had three legitimate children; there was Crassus’ wife, Tertulla—whose husband was rich; there was Brutus’ sister, Junia Tertia—who was pimped by her own mother to get a cut-rate on a lot from Caesar's estate; and there was Brutus’ mother, Servilia—the woman Caesar loved best.

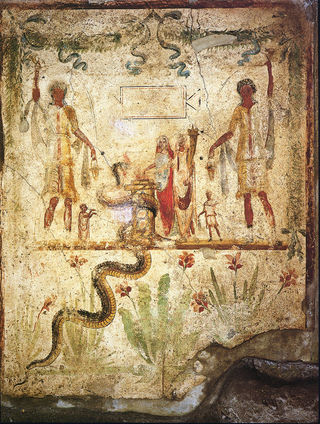

So they called him the father of his country: pater patriae; and they ordered sacrifices to his genius, from the root word gignere: to give birth, to bring forth, to bear, to beget.

They offered the same honors to Caesar’s successors. Caligula swore by the genius of Incitatus, his horse, and had men from good families tortured or sawn in half for failing to swear (“Dare to forbid it!”) by his personal genius. Later, sacrifices were offered to the genius of Nero ("You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons"), though objections were made.

Because the persecutions had started in earnest. Nero rounded up an immoderate multitude of subjects reluctant to swear by his genius and had them put to death. “Covered with the pelts of wild animals, dogs tore them to pieces; or they were hung up on crosses and turned into human torches.” Saint Peter was hung upside down, “at his own request,” on a cross; and Saint Paul, “having taught righteousness to the whole world,” had his head cut off.

Almost a century later, under the adoptive emperors, Polycarp, a bishop from Asia Minor, was brought before his provincial governor and made a martyr. “Swear by the genius of the emperor. Recant,” he was asked. Instead, he was burned at the stake. Others were imprisoned and interrogated under Marcus Aurelius in Lyon, where 48 disobedient subjects were brought up on charges of ἀθεότης, or atheótēs, or atheism, and martyred; another dozen were martyred in Carthage. “We too are a religious people, and our religion is simple,” the proconsul of Africa warned. “We swear by the genius of our lord the emperor and we offer prayers for his salus. And you should too.”

Under the Severans, many who failed to make sacrifices to the fertility and health of the emperor were put to death. Septimius Severus’ governor at Carthage asked Vibia Perpetua, a 22-year-old wife with an infant son at her breast, to offer a sacrifice to the emperor’s health. “Have pity on your father’s grey head; have pity on your infant son. Offer sacrifice pro salute imperatorum: for the emperors’ welfare.” But she would not. So she and her servant Felicitas, another newly delivered mother, were stripped, bound in a net and tossed about by a mad heifer; Perpetua guided the gladiator’s knife to her neck.

A decade and a half after Severus Alexander was assassinated, another emperor posted an edict that ordered sacrifice throughout the empire to his τύχην, or genius, and to his gods. Many apostatized. On 46 bits of papyrus signed and dated after the fall of 249, Decius’ subjects responded: “I have always and without interruption sacrificed to the gods, and now in your presence in accordance with the edict’s decree I have made sacrifice, poured a libation, and partaken of the sacred victims.” Smoke rose from sacrifices all over the empire: infants were rushed to imperial altars in the arms of their mothers or fathers; others swore by the emperor’s τύχην, or genius. But not everybody lapsed. Pope Fabian—who was surrounded by 46 presbyters, seven deacons, seven subdeacons, 42 acolytes and 52 exorcists as bishop of Rome—was bought before the emperor and martyred. Babylas, the bishop of Antioch, and Alexander, the bishop of Jerusalem, were taken to prison, where they breathed their last; Dionysius of Alexandria rode off into the Libyan Desert on an ass.

Then from early 303 to early 304, a series of four edicts ordered the persecutions started again. Many swore by the τύχην, or genius, of the emperor Diocletian; altars were set up in the courts so that subjects could apostatize before their cases came up. Those who declined were whipped, burned, or mutilated on their genitals or bowels. “The prisons were crowded; tortures, hitherto unheard of, were invented; and lest justice should be inadvertently administered, altars were placed in the courts of justice, hard by the tribunal, that every litigant might offer incense before his cause could be heard,” wrote Lactantius, the persecuted teacher from Nicomedia. “Entire families of the pious were put to death,” wrote Eusebius, the persecuted bishop from Caesarea. There were witnesses in Britain, in Iberia, in Africa, in Macedonia, in Palestine, and in Rome. It was impossible to remember the number and splendor of all those martyrs.

Seven years later it was over. In April of 311, Galerius—who succeeded Diocletian—issued the first edict of toleration. Then in the spring of 313, Licinius—who succeeded Galerius—and Constantine drew up another edict at Milan. Subjects were suddenly free to observe any religion without molestation. “The Christians and all others should have liberty to follow that mode of religion which to each of them appeared best,” they wrote. The emperor’s genius was a matter of indifference. The Imperial Cult was a thing of the past.

We can hope it never comes back.

References

Betzig, Laura. 2020. Every kingdom divided against itself: The evolution of Christianity. In J. Feierman and L. Oviedo, The Evolution of Religion. London: Routledge, pp. 271-284.

Betzig, Laura. In preparation. The Badge of Lost Innocence: A History of the West.