Mindfulness

Mindfulness in Silicon Valley: Is Work Becoming Religion?

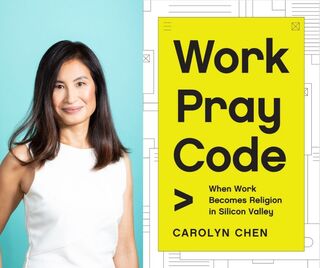

"Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley" is a must-read.

Posted April 11, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Carolyn Chen’s new book about Silicon Valley culture, Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley (Princeton University Press, 2022) is a must-read for anyone interested in the rise of mindfulness in corporate culture, and anyone concerned with how Silicon Valley culture might be shaping and distorting modern ideas of the workplace and the community-writ-large.

Chen, a sociologist and associate professor of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley, interviewed over 100 people for this book. These profiles are interesting and illuminating. She writes

“I met people like the thirty-two-year-old entrepreneur John Ashton (not his real name), who left his tight-knit evangelical community in Georgia to move to Silicon Valley—where he traded his Christianity for an even more zealous faith in the eventual IPO of his start-up.”

Ashton “drinks the Kool-Aid” of his tech firm, and finds identity, belonging, purpose and a kind of transcendence in his workplace, leaving his evangelical community behind.

Another, “Cecelia Lau,” “a thoughtful and articulate Asian American woman with a chin-length bob, moved to San Francisco when she graduated from Dartmouth College in 2014.” Chen describes how Lau was introduced to mindfulness at a start-up in Silicon Valley, but became disillusioned by ethical concerns, left tech, and converted to Buddhism while pursuing a career more congruent with her values. Chen writes, “[Lau] claims that she began to experience the truth of Buddhism only after letting go of her ‘attachment’ to the ‘capitalist’ worldview that ‘we’re all supposed to be megaproducers and efficient,’” a concept promoted by some iterations of corporate mindfulness.

Mindfulness, in the Buddhist tradition, is a tool to sit with, understand, alleviate, and ultimately overcome suffering. No doubt, mindfulness in itself might alleviate some of the suffering workers experience. However, corporate mindfulness often supports productivity as the sole arbiter of self-worth, which is in itself a source of suffering. Moreover, corporate mindfulness is typically shorn from the ethical teachings that accompany it in Buddhism. “Right Livelihood” is a part of the “Eightfold Path” of Buddhism, and one can wonder if the actions of corporate America align with “Right” or ethical livelihood.

Chen also explores “corporate maternalism,” in which corporations provide everything from day care to laundry to fitness centers and snacks, meals, and happy hour drinks, in an effort to glue workers to the workplace. Some corporations even sent their workers weekly snack boxes during the pandemic, as well as paying for mindfulness and other wellness apps and programs. What are the pros and cons of this approach? What happens when workers are displaced from their neighborhoods? Will this change post-pandemic?

Chen asks us to wonder where all this leaves ethics, equity, social responsibility, environmental concerns, and connection to the community beyond the workplace. Another significant question is whether corporate mindfulness will water down the message and practice of Buddhism to the point of absurdity – or whether it will open the door for some to explore further.

Silicon Valley appears to have created an elite within corporate America, one which has developed its own religion, co-opting mindfulness to suit its own purposes. Will workers continue to drink the Kool-Aid? Are we all buying into the religion that says Big Tech (and social media) will solve all our problems, thus disconnecting ourselves from more meaningful engagement with our neighborhoods and communities?

Chen writes (see self-interview in references):

"While many tech workers feel fulfilled and “whole” because of work, others at the margins of the tech industry are living broken lives. There is a social cost to what I call “Techtopia,” a society where work is the highest form of fulfilment. The problem with Techtopia is that work monopolizes the resources of a community—its time, energy, money, and devotion. As a result, people disinvest in other vital social institutions—families, faith communities, neighborhoods, and political institutions. Work becomes the alpha institution, around which all other institutions must submit and cater to in order to get a share of the community’s resources."

In my own book Facebuddha: Transcendence in the Age of Social Networks (2017), I write, tongue-only-partly-in-cheek,

“Social media is not just a medium. It is a new religion. The Tweet is our Call to Prayers. We thumb our Phones like Rosaries. We take Food Pics instead of Saying Grace. The Status Update is our Sermon on the Mount. The Selfie our personal Anointment and Beatification. Facebook Messenger is our Messiah. The Apple Store is our modern Cathedral, our Silicon Sanctuary. New Emoji are released to the fanfare of a new Pope.”

Where are these religions taking us?

Chen’s book is an important rejoinder and counterpoint to the social and cultural challenges posed by Silicon Valley culture in the 21st century.

I was recently in conversation with Chen for the Brown Club of Greater San Francisco, and that conversation is now available on YouTube. (Appended below.)

Sociologist Carolyn Chen Discusses her Book Work Pray Code

(c) 2022 Ravi Chandra, M.D., D.F.A.P.A.

References

Chen C. What the Anti-work Discourse Gets Wrong. The Atlantic, March 22, 2022.

Carolyn Chen on Work Pray Code, March 16, 2022.