Gender

Gender Equality Improves Life for Everyone

Research shows that equality benefits both women and men.

Posted July 31, 2019

This article was written with my colleagues, Professor Andre Audette (Monmouth College) and Ms. Haley O’Connor (Harvard Law School).

Our recent paper "(E)Quality of Life: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Gender Equality on Life Satisfaction," which appeared in the peer-reviewed Journal of Happiness, examines two questions in the context of cross-national differences in human happiness:

- Does greater gender equality promote greater levels of happiness, on average?

- Do increases in gender equality improve the happiness of only women? Or do both men and women benefit, such that we all win with more equality, as far as happiness goes?

We find strong empirical evidence in support of the conclusions that more gender equality implies more happiness; that this applies for men and women alike; and that such results were obtained while controlling for other factors that also affect the cross-national pattern of life satisfaction.

The theoretical reason for these connections are ones that people on both the political Left and Right would endorse. Briefly, (a) how happy people are, in general, is determined by the extent to which their needs as human beings are fulfilled, and (b) we are more likely to be successful in fulfilling our needs when we have the freedom to do so. Thus, less gender inequality (i.e., less gender discrimination) implies a world in which both men and women equally enjoy the same rights and liberties.

Both genders are thus equally capable of their own "pursuit of happiness," unhampered by discriminatory laws or social practices. Progressives will take comfort from the substance of the outcome, believing as they do in equality as an end in and of itself. Similarly, Libertarians and others who believe in the market society ("free people make free choices in a free market") should also be well pleased to learn that when there is indeed a level playing field for all—so that markets are allowed to work as they should in theory—everyone is better off.

Of course, there are critics of gender equality (principally cultural conservatives, rather than economic conservatives), who sincerely believe that equality has a downside. As they see it, promoting the “empowerment” of women, or otherwise making men and women equal before the law, actually has negative effects on women—and thus society as a whole—for two reasons.

The first is that so-called "equality" (they say) really means removing the “protections” offered women by traditional laws and customs that recognize their special status as women. The second (it is argued) is that an equality of gender roles in practice actually harms women (and thus their children and others), because it will increase the life burden of women (e.g., because they would be expected to work outside the home as well as being principally responsible for the household, with deleterious consequences for their well-being, given that their (male) partners are unlikely to accept a proportionate increase in their share of necessary domestic labor). Thus, some believe, the costs to women inherent in equality are greater than the potential benefits.

To test these competing claims, our paper followed the conventional social science practice of looking to see if we could find a statistically meaningful connection between equality and happiness, when controlling for (holding constant) the other major things known to affect happiness. If, again controlling for other factors, we find a positive connection (more equality implies greater happiness), and if that connection is statistically significant (not likely to be due to chance), then we can confidently conclude that gender equality is indeed positively associated with greater happiness.

In terms of equality, we studied not just one, but four different well-known and respected measures, each focusing on a slightly different aspect or definition of equality. These are the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), the Gender Development Index (GDI), the Gender Inequality Index (GII), and the Gender Gap Index (GGI).

Each captures somewhat different elements of gender equality in a country, including, for instance, gender equality in education, pay, and health; women’s representation in government; how long women have held the right to vote; and the degree to which women are equally as likely as men to be managers or hold other senior-level work positions, among other things. Using all four measures allows us to capture a comprehensive assessment of the level of gender equality in society, given, as we find, that each measure leads to the same substantive conclusion.

We combine these data with the standard data on life satisfaction from the World Values Surveys, along with other variables that influence levels of satisfaction, including the individualism of a nation's culture, its level of economic development (as measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita), the unemployment rate, and the yearly rate of economic growth.

In a second set of analyses, we also use data from the Eurobarometer survey, which gives us a longer time period to consider (about two decades). To ensure that the countries analyzed are comparable, we limit our analysis to the industrial democracies of the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

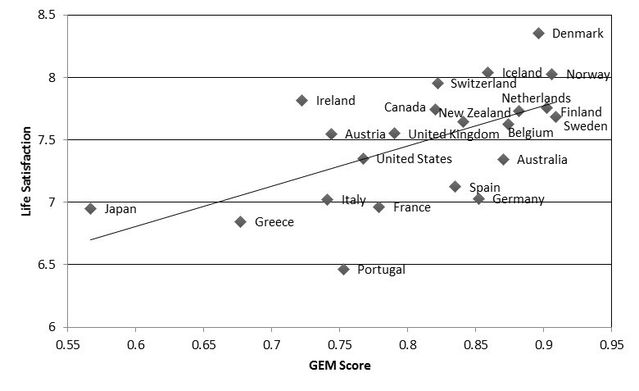

The results all tell a clear and convincing story: The residents of countries with greater gender equality are, on average, more satisfied with their lives than those in countries with less gender equality. For examples, see the figure above.

This figure uses the GEM data, with a higher score along the horizontal axis indicating that a society has greater equality between the sexes. On the vertical axis is the measure of how satisfied, on average, citizens are with their lives on a scale of 1-10. The line that best represents the data is upward sloping (and statistically significant), showing that citizens in countries with lower gender equality (like Japan) tend to be less satisfied with their lives compared to countries with greater gender equality (like Denmark).

We include this simple graph as it is helpful in illustrating the general pattern we find, though we stress that our published paper relies upon more demanding statistical methods that include the "control variables" mentioned above, such that we can be sure that it is equality (not, say, culture or economic development) that is causing happiness to increase.

The results look similar for each measure of gender equality and across all time periods we examined. Moreover, the results suggest that the magnitude of the relationship is pronounced, such that relatively modest increases in equality produce large improvements in happiness.

Thus, the data clearly suggests that we prioritize working for gender equality not merely for its own sake, but also because it contributes to building a better (happier) world.

Our analysis also showed that equality not only affected the overall, societal-level life satisfaction, but also that this improvement did not come at the expense of men's happiness. Nor did it suggest that, as cultural conservatives sometimes argue, women themselves are made less happy by equality. We tested for these eventualities by computing life satisfaction for each gender separately. When we conduct the analysis focusing not on the societal average, but considering the mean for men and women independently, we find that gender equality raises life satisfaction not just for women, but for men too. To be sure, the effect is moderately stronger for women (as we would expect), but only moderately so.

As a familiar aphorism suggests, “a rising tide lifts all boats.” Building a more equal—and presumably more just—society does not benefit only women as the primary beneficiaries of the pro-equality policies, but rather everyone wins from promoting equality and justice.

In sum, the research shows that gender equality benefits society as a whole. Promoting equality thus commends itself as a practical, tangible method for making life better for everyone.

References

The research described above is from:

Audette, A., S. Lam, H. O'Connor, and B. Radcliff. (2018). Journal of Happiness Studies, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0042-8.