Midlife

Physical Activity Improves Cognitive Function

Regular physical activity can improve brain function throughout a lifespan.

Posted April 9, 2014

Every day, a new study is published heralding the benefits of physical fitness. Everybody knows they should probably exercise more... but finding the motivation and the time can be difficult. How much do you work out each week? Hopefully, the new findings that physical activity can improve cognitive function thoughout a lifespan will motivate you to exercise more—regardless of your age.

This week, two studies were released showing that physical activity done today can benefit cognitive function for decades down the road. Countless other studies have shown that regular physical activity and fine-tuned motor skills benefit cognitive function beginning in infancy and continuing through every stage of our lives.

In the first study, researchers from the University of Minnesota found that young adults who run or participate in aerobic activities preserve their thinking and memory skills for middle age. The second study, from Finland, found that middle aged people who are physically active protect themselves from dementia in older age.

Physical Activity in Young Adulthood Benefits Brain Power in Midlife

The first study titled, "Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cognitive Function in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study” was published in the April 2, 2014 online issue of Neurology. For this study middle age was defined as ages 43 to 55. The average age of the young adults was 25.

For the Minnesota study, 2,747 healthy people with an average age of 25 participated in a treadmill test two decades ago, and then again twenty years later. Cognitive tests were taken 25 years after the beginning of the study to measure: verbal memory, psychomotor speed (the relationship between thinking skills and physical movement), and executive function.

People who had smaller decreases in the time it took to complete the treadmill test 20 years later were more likely to perform better on the executive function test than those who had larger decreases. Across the board, the researchers found better verbal memory, faster psychomotor speeds, and improved executive function at 43 to 55 years of age to be clearly associated with better cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) 25 years earlier.

How quickly can you name the ink color of each word?

Specifically, the more fit participants had been as young adults, the better they could correctly state ink color with a mismatched word in the classic Stroop test. ( i.e. for the word "yellow" written in green ink, the correct answer was "green.")

Lead author David R. Jacobs, Jr, PhD, hopes that this study will serve as yet another reminder and motivator for young adults to stay aerobically active. Running, swimming, biking, riding the elliptical, cardio classes... have so many health benefits including long-term improvements to cognitive function.

Physical Activity in Midlife Protects From Dementia in Old Age

The second study from the University of Eastern Finland found that physical activity in midlife seems to protect from dementia in old age. The April 2014 study titled "Leisure-Time Physical Activity from Mid- to Late Life, Body Mass Index, and Risk of Dementia” was published in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

The researchers found that participants who engaged in physical activity at least twice a week had a lower risk of dementia than those who were less active. The research also showed that it’s never too late to start. Becoming more physically active after midlife was shown to lower dementia risk.

The Finnish researchers said recent findings from the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Incidence of Dementia (CAIDE) study also demonstrated that people who engaged in leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) at least twice per week had a lower risk of dementia than individuals who were less active.

The researchers emphasize that staying physically active—or becoming more physically active—after midlife may also contribute to lowering dementia risk, especially in people who are overweight or obese at midlife. These results give some clues for ways to structure exercise interventions that can help prevent dementia and extend the quality of midlife to old age.

Results from currently ongoing trials in Finland—such as the Finnish multi-center trial called FINGER—will provide more detailed information about the specific type, intensity, and duration of physical activity interventions that can best help prevent late-life cognitive decline.

Conclusion: Why Does Exercise Make You Smarter?

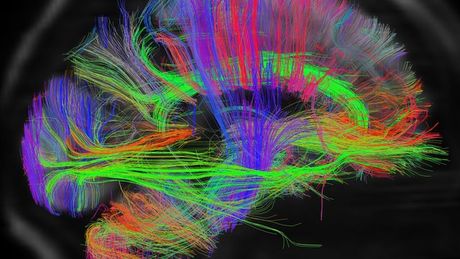

Neuroscientists have known for decades that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is released during aerobic exercise and stimulates neurogenesis (the growth of new neurons). I write about this extensively in the The Athlete’s Way. In recent months, scientists have honed in on an “exercise hormone” called Irisin that is also linked to improved health and cognitive function.

If you’d like to read more on the cognitive benefits of physical fitness throughout a lifespan, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Scientists Discover Why Exercise Makes You Smarter”

- "I Want to Make You Want to Sweat"

- “Irisin: The “Exercise Hormone” has Powerful Health Benefits”

- "Eight Habits that Improve Cognitive Function"

- “The Brain Drain of Inactivity”

- "Better Motor Skills Linked to Higher Academic Scores"

- "High School Athletics Fosters a Lifespan of Well-Being"

- "What Is the Best Way to Improve Brain Power for Life?"

- “Can Physical Activities Improve Fluid Intelligence?"

- “Exercising at a “Conversational Pace” Is Good for Your Brain”

- “4 Lifestyle Choices That Will Keep You Young”

- “What Daily Habit Can Boost “Healthy Aging” Odds Sevenfold?”

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.