Genetics

Why Is Doing Good More Important Than Feeling Good?

Having a noble sense of purpose changes the human genome.

Posted July 30, 2013

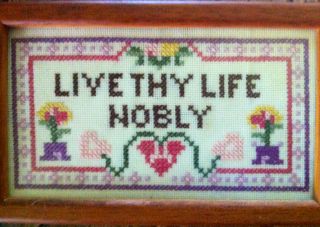

Live Thy Life Nobly

My parents bought an abandoned farmhouse in the Berkshires back in the 1960s. When they were cleaning out the kitchen they discovered a framed cross-stitch with timeless words of wisdom which scientists now realize have a direct effect on the human genome. The cross-stitch said: “Live Thy Life Nobly.”

On July 29, 2013 a study was released which found that doing good—as opposed to feeling good—has a potent beneficial impact on human gene expression and our well-being. The report appears in the online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This is the first study to investigate the impact of different types of happiness on the human genome. Researchers from UCLA's Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and the University of North Carolina set out to examine how specific components of positive psychology impact human gene expression. The researchers discovered that different types of happiness have dramatically different impacts on our genomes.

The driving question of this study was whether different types of positive well-being activated different types of gene expression. To do this, the researchers examined the biological implications of both "hedonic" and "eudaimonic" well-being through the lens of the human genome, which is a complex system comprised of over 21,000 genes that has evolved to help us survive and stay healthy.

Eudaimonic Well-Being vs. Hedonic Well-Being

The UCLA researchers broke happiness into two types of well-being and studied people with high levels of each type. The first category of well-being is called “eudaimonic well-being” which is defined as a type of happiness that comes from having a higher sense of purpose and deeper meaning in life. The second category of well-being is called “hedonic well-being” which is defined as a type of happiness that comes from consummatory self-gratification.

In the new study, people with a eudaimonic disposition showed favorable gene-expression profiles in their immune cells and had low levels of inflammatory gene expression. Eudaimonic individuals also had strong expression of antiviral and antibody genes. Those with a hedonic sense of well-being showed the exact opposite. Hedonic individuals had an adverse expression profile involving high inflammation and low antiviral and antibody gene expression.

For this UCLA study, the researchers drew blood samples from 80 healthy adults who were assessed for hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, as well as potentially confounding negative psychological and behavioral factors.

For the past decade, Steven Cole, a UCLA professor of medicine and a member of the UCLA Cousins Center, and his colleagues, including first author Barbara L. Fredrickson at the University of North Carolina, have been studying how the human genome responds to stress, misery, fear and all kinds of negative psychology.

Barbara L. Fredrickson is a pioneer of fascinating research on the vagus nerve and how Loving-Kindness can create an upward spiral of happiness and well-being. For more on these topics please check out my Psychology Today blogs: "The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure" and "Positive Actions Build Social Capital and Resilience."

Previous studies had found that immune cells are thrown into a systematic shift in baseline gene-expression during extended periods of stress, threat or uncertainty. This chain reaction is known as Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA). CTRA is marked by an increase in the expression of genes which are involved in inflammation and a decreased expression of genes involved in antiviral responses. The researchers used the CTRA gene-expression profile to map the potentially distinct biological effects of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being.

Steven Cole, the senior author of this study, says that the CTRA shift “likely evolved to help the immune system counter the changing patterns of microbial threat that were ancestrally associated with changing socio-environmental conditions; these threats included bacterial infection from wounds caused by social conflict and an increased risk of viral infection associated with social contact. But in contemporary society and our very different environment, chronic activation by social or symbolic threats can promote inflammation and cause cardiovascular, neurodegenerative and other diseases and can impair resistance to viral infections.”

Conclusion: Doing Good Trumps Feeling Good

Individuals with relatively high levels of eudaimonic well-being create favorable gene-expression profiles in their immune cells. Individuals with hedonic well-being show an adverse gene-expression profile. Luckily, deciding to take a eudaimonic or hedonic approach is in the locus of your control. We all have the free will to decide if we are more interested in feeling good or doing good.

Steven Cole concludes, "people with high levels of hedonic well-being didn't feel any worse than those with high levels of eudaimonic well-being. Both seemed to have the same high levels of positive emotion. However, their genomes were responding very differently even though their emotional states were similarly positive.”

"What this study tells us is that doing good and feeling good have very different effects on the human genome, even though they generate similar levels of positive emotion," Cole said. "Apparently, the human genome is much more sensitive to different ways of achieving happiness than are conscious minds."