Happiness

The Resiliency of Happiness

A study of the history of happiness shows that even nations bounce back.

Posted December 16, 2019 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Would you be happier without antibiotics, functional plumbing, and a car? What if you had never heard about these things in the first place, might you be happier then? New research that my colleagues and I published in Nature Human Behavior suggests that it may not really matter.

Questions about happiness are a tricky subject. As Daniel Gilbert points out in his book Stumbling on Happiness: “Few of us can accurately gauge how we will feel tomorrow or next week. That's why when you go to the supermarket on an empty stomach, you'll buy too much, and if you shop after a big meal, you'll buy too little.” If we don’t even understand our own happiness, how can we be expected to understand the happiness of others?

One way to try and get a better handle on happiness is to investigate its history. But how can we do this? The best way we know of, also noted by Daniel Gilbert, is to ask people. The UN’s World Happiness Report, in cooperation with many nations, has been doing this for quite a few years. This has come to be called Gross National Happiness, and some nations have been measuring it in various forms steadily since the 1970s. For example, you can see here that the proportion of survey respondents in the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom claiming to be “very satisfied” with their lives has been rising since roughly the 1980s.

What about before that? Can we see whether people were more or less happy before or after the World Wars? Obviously, we can’t go back and ask them. Not yet, anyway.

But new methods developed by psychologists and computer scientists allow us to examine written text to predict the emotional state of the author reliably. This is called "sentiment analysis" and it involves using words rated on scales of positivity and negativity. When one takes thousands of such rated words and applies them to thousands of words of written text, one can compute the overall positivity and negativity of the text. This, in turn, has been shown to correlate with the emotional attitude of the author.

In recent work, my co-authors (Eugenio Proto, Daniel Sgroi, and Chanuki Seresinhe) and I used this method to compute a measure of sentiment for four nations (Germany, the USA, Italy, and the UK). We then asked if our measurement correlated with the "ground truth" survey measures noted above, taken from the Eurobarometer data. They did with a positive correlation of about 0.53, which is promising, if not ideal. Future work may improve that.

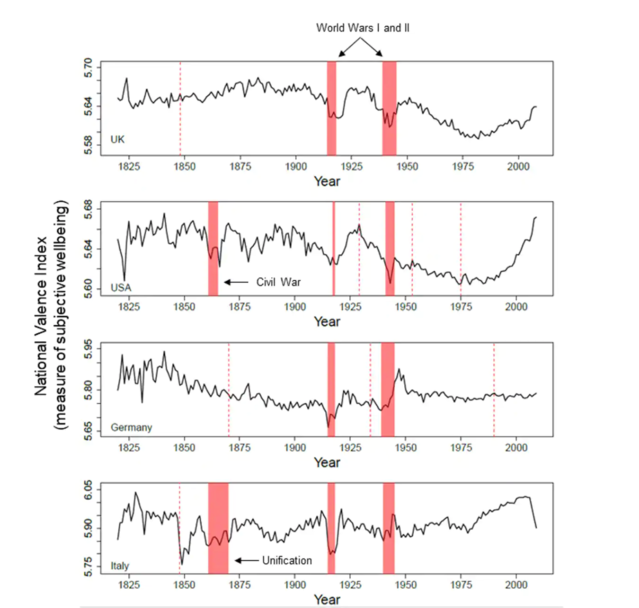

In the meantime, however, we asked if our National Valence Index, a measure of subjective well-being computed for each country separately, might also correlate with historical events, such as wars, the Roaring '20s, and other economic indicators, such as gross domestic product (GDP) and longevity.

The figure below shows the National Valence Index for each of the four countries. The red lines indicated notable historical events. Things look about as one might expect here. Wars tend to reduce sentiment dramatically unless there is censorship (well-known in WWII Germany). The Roaring '20s leap sentiment upwards, and the British Winter of Discontent is a trough, mirrored fascinatingly by a similar bust in American sentiment.

What is perhaps most fascinating, and important for national happiness, is that sentiment tends to be quite resilient over time. People bounce back from wars and fall predictably from highs.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is often assumed to be correlated with subjective well-being. The data on this is mixed, however. Several recent studies have shown the opposite (e.g., Campante & Yanagizawa-Drott, 2015). And our data support a similar reticence. Though GDP has increased roughly across all the nations over the last 200 years, the National Valence Index fails to show a similar rise.

Indeed, longer and presumably healthier lives are a good match for GDP. One extra year of life is worth about a 4.3 percent rise in GDP in happiness-equivalents. Lifespan also has increased over the last 200 years. In the UK in the 1900s, the average lifespan was about 50. It is now around 80.

One goal of having a measure like this is to help policymakers see how their policies and other historical events (that might be prevented) influence the subjective well-being of their constituents. And since subjective well-being has also been shown to improve economic output, one may get double the bang for one’s buck by attending to happiness over economic output.

Still, the question of what makes us happy is rather open. The lack of antibiotics is probably not what made people happier in the 1800s. Indeed, comparisons across time like this are rife with unlikely assumptions. The writers in the 1800s were not the same kind of people who were writing in the 1900s, for example. In our work, we deal with many of these kinds of problems by comparing across nations at the same time and doing this across many years.

Nonetheless, even as our measures improve, I suspect the single most common finding will be that happiness goes up, and then it goes down, and when it goes down, it will later go up, and so on. Call it a scientific endorsement of Buddhism's middle path. Or just call it a reminder that the sun will shine on your back door someday(s), guaranteed. Unless your house is facing north.

References

Campante, F., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2015). Does religion affect economic growth and happiness? Evidence from Ramadan. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 615-658.

Hills, T., Proto, E., Sgroi, D. & Seresinhe, C. (2019). Historical analysis of national subjective well-being using millions of digitized books.