In the Oliver Stone film Wall Street, Michael Douglas’s character infamously tells a colleague that he isn’t going to lunch; he doesn’t have time for lunch because “lunch is for wimps.” In the movie and television industry, it seems that the general attitude is that sleep is for wimps. For many years, production crews in the United States and elsewhere work long hours dictated by shifting production schedules. Unfortunately, these unpredictable schedules can lead to severe sleep deprivation, which research has shown can have dire consequences. The brain doesn’t work well when it is deprived of sleep. This article is written from my perspective as a sleep scientist, along with Russell Williams who has been in the movie production industry for decades.

Perspective from sleep science

In a previous article we focused on the amount of sleep a person needs and concluded that some individuals can get by on less sleep and others (for example, some world-class athletes) require much more. Chronic deprivation of sleep can result in many adverse effects on a person’s health. In this article, we’ll focus on the acute effects of insufficient sleep on a person’s sleep and performance.

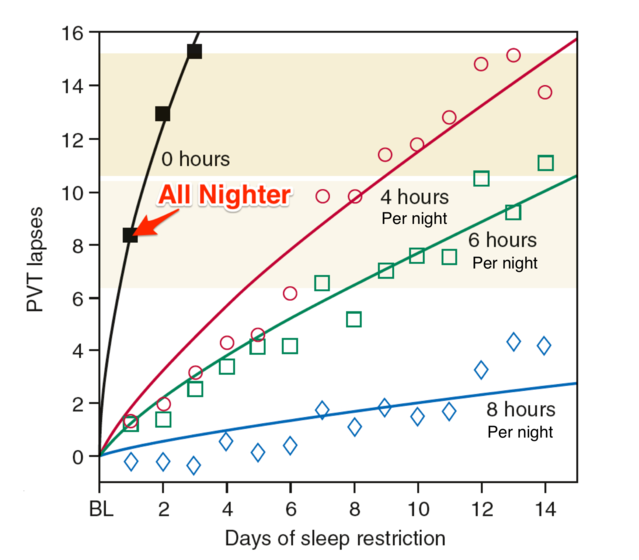

If a person stays awake all night and is tested the following day, it is pretty easy to document that their brain doesn’t work well. This experiment has been conducted by sleep researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. For example, people are supposed to respond to a light on a computer screen and we measure whether they respond and how fast they respond. After a night without sleep, the person will start to have lapses (called PVT lapses in the figure below). The light flashes, but they don’t respond at all even though they are staring at the screen, or it may take much longer to respond. Their brains experience microsleeps that may last only seconds.

If a person sleeps four out of every 24 hours, after about a week of this minimal sleep schedule their brain responds as though they had been up all night. The impairment has accumulated. Even if they sleep six hours a night, after about two weeks, their brain reacts as if they hadn’t slept at all. They have microsleeps and lapses, which are dangerous because if a person falls asleep for just one second while driving 60 miles per hour, the vehicle will have traveled 88 feet in one second. And, when that person awakens, their reaction time may be very slow.

Many industries, especially in transportation and medicine, have attempted to create rules to ensure that the public is protected from sleep-deprived operators. Would you want the pilot of your flight to only have slept four hours? Would you want to drive near a tractor-trailer when the person operating the vehicle has been on the job for 16 consecutive hours? Would you want a doctor who has stayed awake for 36 hours to perform surgery on you?

Similarly, in the movie production industry there are several factors that impact sleep, including very long work hours that force a person to stay awake when the brain’s circadian clock is expecting sleep. So, what is the harm for someone working on a movie or TV production set for 16 hours?

Perspective from film production—Russell Williams

I lost two really good friends in the movie industry as a result of sleep deprivation. One was a stuntman who fell asleep at the wheel after working all night and collided head-on with a semi-tractor trailer. The other was a standby set painter, who had worked long hours the night before but had an early call the next morning. He crashed directly into the back of a truck that had stopped in the middle of the Ventura Freeway and essentially blew himself up. He was known as a good driver, so it is highly unlikely that this accident would have occurred if he had had the proper amount of rest.

One of the checks and balances put in place decades ago to ameliorate long hours on movie and television production sets and enable people in the cast and crew to get needed rest is a concept called “turnaround.” It generally works like this:

For Actors. Turnaround is contractually stipulated if they are members of the Screen Actors Guild. Their turnaround is contracted at 12 hours. This means that if a particular cast member finishes shooting at 7 pm they cannot be called in before 7 am the next morning (or 12 hours of turnaround) without stiff financial penalties being imposed on the production company.

For the Crew. Generally, the crew must be on set before the actors arrive to light the set and set up sound and camera equipment, props, set dressing and whatever else the production day requires. The shooting crew generally gets a 10-hour turnaround, meaning that if they are finished by 7 pm the previous evening, they can be called in at 5 am the next day. The people that generally coordinate all the gear and vehicles to and from the locations on a union film are members of the Teamsters Union. Since they generally are the last to leave a location, especially if it requires traveling to a different part of town, a different state or on a plane to a different country, assuming they will be working the next shift, they have as little as an 8-hour turnaround time.

The Others. This includes nonunion members of the crew (e.g., production assistants and interns) They usually get between 5 to 6 hours of sleep at best, which seems reasonable, even with turnaround intervals, but this doesn’t account for the amount of time the crew or cast member may have to travel before they can actually get to bed and begin the sleep cycle.

As we’ve learned above, research indicates unequivocally that the effect of sleep deprivation accumulates in the body, and the brain will find the earliest opportunity to settle that sleep debt.

I remember having great difficulty falling into some sort of regular sleep pattern while working on productions. On a typical production shoot, especially one that continues for months, he might begin the day early on Monday morning (for a 6 or 7 am “call time”), and work 12 hours before ending. But suppose the day lasted 14 hours? That means the next day you may be starting at 9 am and working another 14 hours until 11 pm. This brings your call time to noon the following day. If this pattern continues, and it almost always does, it’s practically an immutable fact of show business that by the time you begin work on Fridays, call time may be between 6 and 7 pm. You will inevitably work all night until the sun rises on Saturday morning!

If you return home between 7 and 8 am, you can force yourself to stay up all day, sleep for about 2-5 hours, and then get in step with the rest of your day. You might have personal things to take care of. You might even have something related to the movie that must be done over the weekend. So that leaves Sunday to hopefully get some rest because typically on Monday morning you’ll be back on an early call time. With this type of shooting schedule, which is very typical of the movie and television industry, how does one even have a predictable circadian rhythm?

The circadian clock in your brain wants you to sleep at night. But what if production must take place late at night? When you see the footage showing a scene where the actors are outdoors during the night, in most cases, that scene was shot during the night (what we refer to as a “night exterior”) because you can’t black out the whole world with yards of cloth known as Duvatyne. So you might consistently stay on a night schedule. The saving grace in most cases is that when the sun rises. That’s a wrap except for maybe small insert shots or close-ups. So theoretically, you should be able to get 7-8 hours of sleep when you get off from working night exterior if you factor in your “turnaround.” But for someone like me, I very rarely get that full complement of time because when the rest of the world is up and moving around, the noise of the day keeps me awake!

In order for me to get a sufficient amount of sleep during the daytime, I need almost complete sensory deprivation, such as blacked out windows, an eye mask and earplugs. I also may need some background sound (for example, from a noise machine) to block out and absorb the sounds of the city because as soon as I start hearing things moving around, my mind tells me that I should be up and doing those things.

I can tell you for a fact that there were several productions that were offered me that I declined. Once I read the screenplay and realized that to get these night scenes they were going to probably have to shoot more than 3 or 4 weeks of night exteriors, I generally turn the project down just based on that. Why? Because I am a very unpleasant person when I come in day after day without sleep, and if you’re really going to work on high-level television and film projects, it might behoove you to be in a good mood and be collaborative because it’s going to be a long day and the worst thing you want to get is a reputation as someone who is grumpy and grouchy.

For me, night exteriors were the worst. Driving home in the 1000 square miles of LA County can become very boring and monotonous after you put in a 12, 14, or 15-hour night. You’re trying to navigate your way home when everybody else is just leaving for work fresh and alert. I remember one morning, I was driving home with less than a mile to go. Driving uphill in my cargo van, I drifted off to sleep for what seemed an eternity. In actuality, it may have been only three or four seconds but my eyes were closed long enough to realize that I had drifted across the center lane of a 5-lane thoroughfare. As the hill had reduced my speed and the angle of attack was so shallow, had I not awakened at that precise second, I would have sideswiped at least five or six cars. Also, I was indeed very fortunate that no one was coming down the hill, as I was in the southbound right lane going North. I was lucky that time as I have been every other time so far that I have drifted off to sleep after an all-night shoot.

Within the entertainment business there has been much discussion, pushback, documentaries, (the most famous being by Haskell Wexler), requests to change policy and efforts to enforce regulations to prevent a movie company from working its crew and cast to the point that they can barely stand. State governments have also weighed in, but the reality of show business is that the work hours tend to be long and the sleep hours tend to be short. And that’s on a good day.

A final word from Meir Kryger and Russell Williams

Sleep deprivation related to work schedules and lifestyle can have a devastating effect. It can harm the person who is sleep deprived and harm the public. Society needs to understand that sleep is not for wimps. It is for all.

Meir Kryger MD FRCPC, Professor, Yale School of Medicine (author of the Mystery of Sleep)

Russell Williams, II, Distinguished Artist-in-Residence, Film and Media Arts Division, SOC, American University (Honors: 2 Academy Awards; 2 Prime Time Emmys for Sound Mixing)