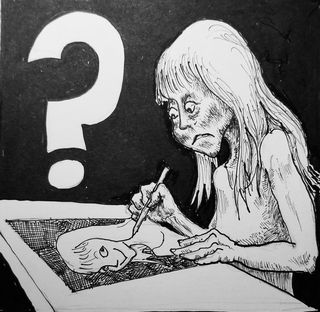

Trauma

How to Use Stories to Heal

Narrative therapy aims to deconstruct false narratives and propose new ones.

Posted December 16, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

When someone leaves you,

they flow out of you like milk,

and if you allow it, you can feed people …

(Emily Berry, "from Unexhausted Time'")

Last month I had coffee in Paris with Richard. He was originally a friend of my brother Louis's and has become a close friend of mine. We met in a café in the seventh arrondissement, less than a mile from the site of the Vel d'Hiv, where 13,000 Jews, including over 4,000 children, were sent in 1942 before being transported to concentration camps.

We talked about Louis, who died of cancer in 2013, and I was telling Richard that the loss of my brother, along with some other types of loss (including death of parents, and of an infant son, and the far less tragic syndrome of the empty-nester) had combined to create a kind of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that was preventing me from getting on with my life. It wasn't just me making this diagnosis, I continued, somewhat defensively: At least one therapist had said the same thing.

Richard frowned. "But you can't look at a loss that way," he told me (I am translating here). "You don't forget what you've lost, you don't forget your brother, but you choose to think of him as a positive and wonderful story, which he was—is. Someone whose life was full of joy, who is now part of your own strength and personality, who wants you to go on."

I wasn't sure why, but Richard's words had a powerful effect on me. And I realized that what he was advocating in my own life was something I'd been researching, intellectually, for a while: how humans are the stories we tell of ourselves, and how this fact logically implies opportunities for therapy, for healing.

In my previous post I quoted Wilhelm Schapp, who claimed there is no difference between a human and the tales a human tells of her- or him-self. The entire existence of humans and their world, Schapp wrote, consists of stories they tell themselves, both stories of what happened in the past and stories of what they plan for the future. It follows, logically, that one way to heal psychological trauma might be to change those stories, as Richard suggested.

The discipline that embodies this approach is called narrative therapy, and it was originally propounded by Michael White and David Epston in the 1980s. It starts with a similar premise to Schapp's, positing first that our identity is based on a story or "discourse" that is (1) socially constructed, (2) expressed through language, (3) maintained via narrative, and (4) lacking absolute truth.

The narrative approach views the patient as someone not sick or dependent, but rather as an expert in the problem s/he is fighting, an expert in the false discourse that created the problem. The person is not the issue, according to this viewpoint: "The problem is the problem" and is the end result of twisted or false stories that "dominant voices" in a person's environment have imposed.

In such a worldview, the therapy consists of a process of "deconstruction," of separating the person from her "problem" and the historically dominant negative stories through which she sees herself, making her aware of alternative, positive stories offering constructive possibilities, which are validated in her own life by supportive side-narratives and the individuals associated with them.

One example—going back to PTSD—might be survivor's guilt which, amid a cloud of grief, saps an individual's drive and optimism by suggesting that the individual should have done more to save a loved one or, in more cosmic terms, should have died in the loved one's place. A narrative approach to this problem might be to drill down to myths of original sin in Judeo-Christian theology and to paternalistic tales of responsibility and duty imposed by the typical Western family in a patriarchal culture. You don't have to read the fables of La Fontaine or the Brothers Grimm to understand how the "thin" story (White's term) of a child's responsibility to the family implies guilt and punishment when things go wrong: when the family self-destructs, or a family member dies.

An alternative and "fat" therapeutic story would not deny personal responsibility, but rather recount how each family member embodies the strengths as well as the weaknesses of every other person in the family, and how the happiness and progress of a survivor must be deeply wished for and supported by the rest of the group, both living and dead.

The aim here is to find a "unique outcome ... in which the problem does not feature ... to alert the client to exceptions to the dominant story that often go unnoticed." This outcome turns personal loss into a gain for the survivor's world. It's an approach that, thanks to my friend's comment, turned around my own way of thinking about loss: not dramatically but gently, and I think fundamentally.

Yet there are many kinds of loss and trauma that remain simply too vast to deal with by tweaking the dominant story, or by creating a happier alternative with a unique and positive outcome. And the question then arises: What answers could come from changing the story one tells of such a person's life and people? How, to cite Adorno's example in the last post, could a poem do anything to palliate the agony and losses of the Shoah?

Perhaps the answer lies in the political dimension of narrative therapy: the perception that the "thin" stories lying at the heart of dysfunction are deeply political in nature. No one whose family was rounded up in the Vel d'Hiv and subsequently murdered could take worthwhile refuge in an alternative story. No one who suffered Auschwitz can build a happy narrative from such trauma.

But what they can do is analyze the fake myths, lies, and propaganda that Fascism generated and that set the stage for the Holocaust. They can examine the many tales of heroism and self-sacrifice that allowed victims of Nazi repression to survive.

Even more importantly, their survivors can examine with utmost care the false narratives, both personal and political, that twist the world they currently inhabit.

In a country like the U.S., whose sitting president has been found, by various fact-checking bodies, to have uttered well over 10,000 lies or misleading statements in his three years in office; whose key adviser recently justified an outright falsehood by calling it an "alternative fact"; a society where untruths and exaggerations, instantly disseminated over social media, gain currency on both sides of an increasingly vast political divide, whether they are eventually disproved or not—such examination becomes not just a vital political act, but an expression of the most fundamental, and the most essential, of human qualities.

References

White, M. (1995a): Re-authoring lives: Interviews and Essays. Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications