Media

Will Apple and Google’s New Apps Change Addictive Phone Use?

Perhaps, but first we have to change our brains.

Posted June 13, 2018

[Note the "Update" appended to the end of this post for further information and thoughts.]

Recently, Apple and Google announced the introduction of phone apps for the iPhone (Screen Time) and Android devices (Digital Wellbeing) that are designed to “discourage smartphone overuse.” An excellent summary of the apps can be found here.

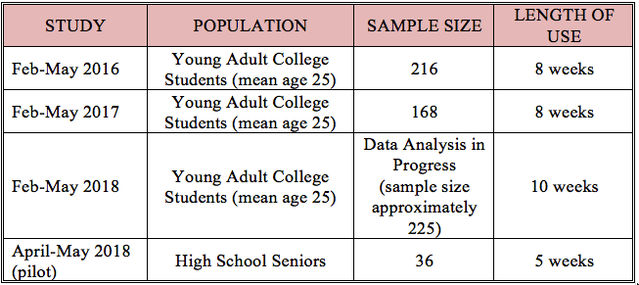

In our lab, we have had college and high school students monitor their smartphone usage for long periods of time since 2016 using the Instant Quantified Self app and the Moment app. The table below shows the relevant information about our four studies. [NOTE: our college students are 25 years old on average and most have full-time jobs and a family so they are more like young adults living in an urban area who happen to also go to college.]

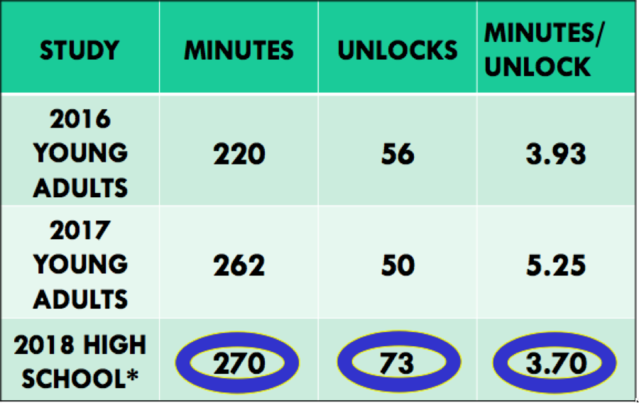

The results are shown in the chart below. Several facts are clear. For young adults, usage changed dramatically over the year from 2016 to 2017 increasing 19% from 220 minutes per day to 262 minutes per day with number of minutes spent on the phone per unlock also increasing from just under 4 minutes per unlock to more than 5 minutes per unlock, a 33% increase of more than a minute and a quarter. My perusal of the raw data collected this spring suggests that those numbers are going to continue to increase. We also collected similar data in a pilot study with high school seniors and while their daily usage increased to 270 minutes, their number of unlocks skyrocketed to 73 per day resulting in using only 3.7 minutes per unlock.

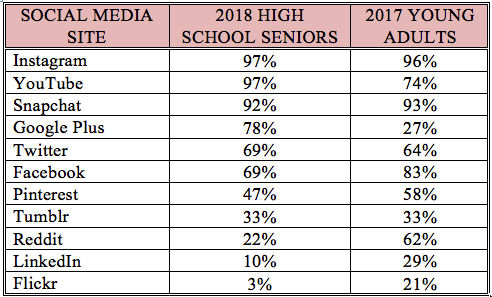

Further examination of the data indicated an interesting trend when we collected data on social media involvement. Using the top 11 social media sites by unique monthly visitors, we found the following percentages of active users shown in the chart below, which are organized from the highest percentage of high school seniors having an active account to lowest percentage having an active account.

Note that more than 90% of high school seniors had accounts on three social media sites (Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat; two of which are relatively new), and more than two-thirds had active accounts on three more (Google Plus, Twitter, and Facebook). Compare these statistics to the young adults where more than two-thirds had active accounts on four sites (Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and YouTube) with only the first two having more than 90% involvement. From these data plus the data in the chart above it appears that the driving force in spending more time on a smartphone may be social media and while young adults are checking in for more than 5 minutes at a time, high school students are only spending less than 4 minutes doing the same with even more social media commitments. Adults most likely spend more time perusing the posts while high school students open the app, click "like," and close the app. We will know more about the high school students’ behavior when we run a full study for the 2018-2019 school year with a larger sample.

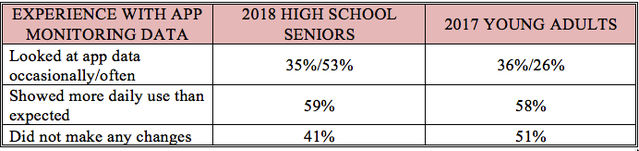

So, will Apple's Screen Time app and Google’s Android Digital Wellbeing app change this behavior? I have my doubts. Here’s why: At the end of each study, we asked the participants how often they looked at the data, whether the app showed what they expected and if they made any changes based on what they saw. The data for the two groups where we collected these post-study observations are shown below and are pretty striking. While the majority of young adults and vast majority of high school seniors looked at the data at least occasionally and half of each group felt that it showed more daily use than they had expected, 4 in 10 high school seniors and half the young adults did not make any changes in their checking behavior.

When asked why they had not made changes, common responses included:

At the beginning, I tried to reduce my usage but after about a few days I had completely forgotten about it.

Overall I expected for my data to be relatively high. I was also shocked by how on school days my phone usage is way less than when I don't have school!

I found that the amount of time that I use my phone could be reduced. The effect that using the phone has on my schoolwork is alarming, and I should reduce the time. Many things could be accomplished in my life if I was to stop using my phone as much.

Based on what we have seen in our studies, both those that I have excerpted here and many others, I don’t see a great hope that simply telling someone that they are spending too much time on their phone is going to actualize a reduction in its use. You cannot change the behavior without changing the “psychology” that drives the behavior. It appears, from all of our work and that of others, that about half the time someone checks their phone it is because of an external interruption such as an alert or notification. As Dr. Nancy Cheever has shown on 60 Minutes, Good Morning America, and Katie Couric's National Geographic special "Your Brain on Tech," among others, not being allowed to check an alert causes a spike in galvanic skin response indicating arousal (and not the positive kind!). That is easy to change: Just remove all alerts and notifications. Then plan to check social media and other communications on a schedule that reduces the checking-in behaviors. It may take some time as these habits are now very ingrained in our biochemistry, but it will work if you are persistent.

What about the other half of the times we check our phones when there is no external alert or notification? Actually, there are alerts and they are coming from inside our brain. In our work, we find that a major predictor of overuse of technology in general and smartphones, in particular, is anxiety that is often referred to as nomophobia or FOMO. Regardless of what you call it, anxiety often drives us to check our phones. So does boredom. We no longer are willing to sit with our thoughts without needing to do something and that little box has so many somethings to occupy our minds. What can you do? The key is teaching yourself to be aware of the anxiety and slowly wean yourself off of having to check in so often and on a whim. I have talked extensively in my Psychology Today blog posts as well as many of my books about learning how to take tech breaks and use the time for going out in nature or doing other activities such as meditation, listening to music, or talking to someone live that neuroscience has shown serve to calm our brains. Another easy strategy is to move all “social” apps to the last home screen and bury them in a folder so that you have to literally hunt them down and, perhaps, the few moments it takes to do that might give you pause to reflect on why you are actually checking in so often.

So, I ask again: Will these new apps work? I will reframe the question and ask you: Do you use Apple’s Night Shift or Android’s Night Mode which were introduced to help users avoid the blue light that retards melatonin and produces cortisol promoting a better night’s sleep? In my informal surveys, nearly everyone seems to know that blue light is not good for your nighttime sleeping habits and yet very few use the very function on their phone that would reduce the blue light.

Overall, I suspect that knowledge from the new apps will sway some to back off excessive use of their smartphones but the majority will ignore the data and keep checking in more and more often. With all those social media sites and other communication modalities, we have given ourselves a large social responsibility to get on more often and stay on longer. Until we deal with this issue, the new apps will not really change much at all.

UPDATE: Since this post, Instagram and Facebook have jumped into the fray with their own algorithm of calculating and informing you about your use of their apps. Details can be found in this Wired Magazine article: Want to Curb Phone Use? Facebook and Instagram Have an Idea. As I mentioned in my interview for the Wired article, each of these companies is supplying the "what" by showing the user how much time has been spent (wasted?) using a smartphone or a particular smartphone app. Still remaining is for the user to determine the "why" and the "how." The "why" refers to what is driving the excessive use behavior and our research has narrowed in on several physical and psychological reasons, all of which are detailed in Adam Gazzaley and my book, The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World (MIT Press). Briefly, they include easy accessibility of technology, anxiety about not having available technology, fear of missing out on social media posts, poor metacognition, smartphone addiction (aka problematic Internet use), and boredom. Research has supported the impact of each of these "whys" although most of the work in my lab has confirmed the strong impact of anxiety as well as metacognition in impacting obsessive technology use. The "how" refers to how one might begin to reduce the excessive checking in behavior and the constant nagging feeling that you must always be connected or suffer the consequences (of what most people cannot tell us, but they are consequences). There are multiple strategies described in the last two chapters of our book that include those gleaned directly from neuroscience research as well as those with strong behavioral research backing. WARNING: If you are willing to apply any of our suggestions/strategies don't expect the "what" to drop dramatically in a short time. We have all gradually increased our time on our smartphones over the past decade and backing off may take some time as the behavior has been strongly reinforced for many years. Our latest datais encouraging as there is a "suggestion" that we may have reached a peak. The data for our 190 young adults from early 2018 showed that the minutes per day spent on a smartphone stayed constant at 260 minutes (not a meaningful rise from the 262 minutes we found a year prior). That is encouraging. HOWEVER, those same young adults checked in 71 times a day which is a huge increase from the 56 times two years ago and 50 times a year ago. This means that they are checking in more often for shorter periods of time (3.66 minutes per check-in compared to 5.25 a year ago). We are working to understand this massive increase although one shouldn't be surprised as we see everyone on their phones, constantly checking and locking and checking and locking and on and on. We will continue to monitor this behavior with young adult college students as well as high school students and report back as we have more data to share.