I recently took a road trip with my daughter to four national parks in the upper northwest United States and Canada. As she was on crutches I had a lot of time to observe people and how they “appreciated” nature as I follow her up and down trails. On a hike up to the top of Inspiration Point in the Tetons (my amazing daughter actually made it to the top on crutches, a one mile climb that rose 420 feet to 7720 feet above sea level), I spent some time watching people as they reached the pinnacle and encountered a truly inspirational vista.

You may be surprised at what I observed. Out of at least 100 people that I watched during the 30 or so minutes we spent eating lunch and enjoying the view, only a small handful stopped to gaze out at the panoramic view before yanking out a phone or camera and rapidly snapping photos. As we drove through five states and one province, I noticed that nearly everyone—regardless of age—spent more time viewing the wondrous beauty of the parks through a tiny camera lens than simply through their eyes.

Can you really enjoy visual images through a camera lens? I have asked people on my travels about why they shoot so many photos and spend so much time making sure that they get the “perfect” shot and the answers seem to almost always split into two categories. Most people claim they do it because they can. Unlike the old days of film where every photo was precious and cost money, digital cameras afford us the opportunity to take nearly an infinite number of snapshots at no cost in our quest for that one photograph that captures the scene. The second group of answers surrounded “sharing” the experience. At the top of another mountain peak we mysteriously had a telephone signal and at least half of the people were excitedly uploading their just shot “perfect” photos to Facebook while ignoring the view that they just captured on “film.”

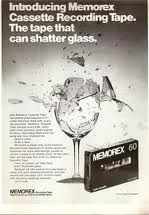

If you are old enough to recall the days of audiocassette tape, you may remember a commercial aired beginning in 1971 for a company called Memorex, which asked the question, “Is it Live or is it Memorex?” In the commercial Ella Fitzgerald sang a note that shattered a wine glass while her voice was being recorded on a Memorex tape. When they played the tape Ella’s voice still shattered a glass.

I always thought that this was a cool demonstration of how you can get the same experience from listening to a recorded song compared to a live song. Granted, audiophiles will argue that the audio experience is not the same when listened to through a recorded medium and they are certainly justified since recorders do not capture all of the overtone and undertone frequencies that are out of our natural hearing range. And avid concertgoers will also argue that the experience of listening to a song on tape is not the same as hearing (and seeing) it at a concert venue. They are both absolutely right. But we listen to music on all sorts of digital media and most certainly get the feeling of the experience.

But I wonder about visual experiences. Do we get the same “experience” from a photograph as we do from simply taking mental snapshots by moving our head and eyes around and taking in the entire scene? One day I decided to test my theory that the experience was not only not the same but also that the omnipresent camera detracted from the total sensory feeling of looking at nature. For one day, I stopped taking photos. I simply looked around and allowed my brain to take in the entire sensory experience including visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic, and olfactory. Although the drive to whip out the iPhone and snap a photo (or two or a dozen or more) was omnipresent—and I was surprised at how that phone in my pocket seemed to beckon to me—I forced myself to just perceive the environment. What a difference it made! First of all, I realized that I had been missing out on some spectacular vistas that I was not capturing with my camera. Instead of looking for the perfect shot I swiveled my body around 360 degrees and realized that I had been missing a whole lot of what was there. I looked behind and to the side of me—something I may have missed while shooting straight ahead—and I watched other people, examined trees, looked at the different shades of colors, smelled the world and saw it from a totally different perspective. While almost everyone else snapped their shots and walked on, I felt as though I was getting a richness that they were missing. Even my lunch tasted better when I was not consumed (sorry, bad pun) by thinking about taking yet another shot of a waterfall or a mountain. My brain was literally overflowing with sensory stimulation. My dreams that night were spectacular.

The second thing that I realized was that my choices of what sights to see were often predicated on what I was told were must-see vistas. And somehow I felt that I had to see them and to document that I did so in order to feel that I had completed a successful trip. And finally, I felt that I was “compelled” to get those perfect shots of the required sights and rapidly rush to get them posted online to affirm my success to my Facebook friends

I have been a research psychologist for nearly 40 years and have spent most of those years immersed in a variety of research paradigms including survey research, observational studies and empirical laboratory-based studies. Recently, my colleagues and I in the George Marsh Applied Cognition Lab at California State University, Dominguez Hills received a grant to get an fNIR device, or a functional near-infrared spectroscopic brain scanner.

This device monitors oxygen molecules in the all-important prefrontal cortex includes areas that are involved in attention, working memory, decision-making, impulse control and even multitasking. Since we acquired the device and installed the hardware and software and tested it on ourselves I have started to think more about how we experience our world. Being hooked up to an fNIR while performing an n-back task—a performance task where the subject is presented a series of stimuli and must decide if they match another shown “n” steps earlier such that seeing CFC in a 1-back task would require the subject to press a button while seeing RTYR in a 3-back task would similarly require a positive response—and then looking at the areas of my brain that were active gave me an interesting perspective on how even the front portion of our brain processes stimuli on so many levels at the same time. And when you consider that sensory input is always being processed elsewhere in the brain you begin to realize the vast amount of processing that is active at any given time.

[As an aside, when I talk about this to my students I often introduce a video showing a young man’s brain being scanned while he is watching a trailer for the movie Avatar.

This is the product of a company called MindSign Neuromarketing, which has posted a variety of videos showing brain scans of movie trailers, advertisements and even speeches. It is fascinating to watch how the brain is constantly processing information.]

Recent research by Peter Aspinal and his colleagues in Edinburgh and London examined brain activity using a mobile EEG to record the emotional experiences of people first walking in an urban shopping area, continuing their walk in a park and finally walking down a street in a busy commercial district. As the walkers transitioned from the urban area to the “green belt” their brain activity showed reductions in arousal, frustration, divided attention and engagement (directed attention) as well as an increase in meditation. As the walkers left the green belt to the busy commercial district their brain activity again changed showing a heightened state of alertness. The authors note that these results are directly in line with Attention Restoration Theory, which I wrote about, in my latest book, iDisorder:

According to research on “Attention Restoration Theory (ART),” when someone interacts with a natural environment their attention is captured in what is referred to as a “bottom-up” process, meaning that it is driven by calming external stimuli seen in nature, allowing the parts of the brain that are overworked to recover. In contrast, according to this theory, urban environments contain stimuli that capture our attention dramatically with sights, odors, and sounds, which requires attention to overcome the aversive stimuli and leads to less calmness and more residual brain activity at the attention level.

As I observed people fervently using their mobile phones in awe inspiring vistas I wondered what their brain scans would show? Would they be getting the calming, bottom-up effect of nature or would they simply continue to accrue more of the top-down, stimulus-driven alertness due not to natural stimuli, but to artificial, electronic stimuli? My guess is that their brains are missing out on something very important and very “restorative.”

I confess that I enjoy lurking and eavesdropping on people as they traverse our world and over the past few years I have noticed, as I assume you have too, that when someone has a moment without a defined task, their attention is invariably drawn to their smartphone. I have not data to support this, but I am certain that this has become more universal among people of all ages. As I walked my dog yesterday morning I noted that most of the people walking their dogs or just strolling were checking out their phones and not the rest of the world. I also observed that the school crossing guard, in between trips with children, was looking intently at her phone as was the mother waiting at the stoplight to make a left turn. As my dog and I sat outside of a coffee shop I glanced around and every single person, regardless of whether they were alone or “with” someone else, was entranced by a smartphone. Later that afternoon, as I waited in line at the grocery store, I counted 18 people waiting in four lines and 16 of the 18 were engrossed with their tiny screen. Only two were involved in conversation.

I don’t want you to assume that I am a naysayer, a technophobe or simply anti-technology and am railing against it. Quite the opposite is true. I have written extensively about the virtues of technology in education and elsewhere and I own nearly every gadget imaginable and have accounts at more social media websites than I can count. What I am seeing in my research and that of others is a growing obsession or compulsion to constantly check in with our technology often at the expense of engaging with the people around us or even the world around us. It is time to take stock and set some limits on our behavior. Instead of reading your email while you are in a grocery store line, start a conversation with the person next to you. Instead of walking around with your face staring down at your smartphone screen, try looking at the world.

Our brains need “restoration” and we don't seem to get that from constant attention to our virtual worlds. Instead we need to pay attention to the real world and the people who inhabit it. You don’t have to give up your phone or go on a technology detox as was suggested in a recent New York Times article. Aspinal’s walkers spent about 8 minutes in the green belt and that led to a marked increase in restorative brain activity. In iDisorder I recommend that you take 10 minute breaks every 90 minutes to two hours and do something restorative: walk outside, exercise, talk to a real human being, listen to music, meditate, or do something that you personally find calming. It is too easy, and too compelling, to spend our lives engaged with our virtual worlds and we are doing so at the expense of our brains and our mental health. You don’t have to give up your phone, computer and other electronic devices but I do recommend that you try taking short technology breaks that will restore your brain and help you feel better and, most likely, function better when you are immersed in technology.